Ahead of the 2016 election, many commentators speculated that Donald Trump’s “woman” problem would effectively hand the election to Hillary Clinton. In new research Erin C. Cassese explains why this was not the case. Using data from the American National Election Study, she finds that Republican women are much closer to Republican men than Democratic men or women on every issue but gun control. Republican women, she writes, are just as ideologically extreme as Republican men, and will vote for their party’s candidate regardless of policy appeals or accusations of sexism.

Ahead of the 2016 election, many commentators speculated that Donald Trump’s “woman” problem would effectively hand the election to Hillary Clinton. In new research Erin C. Cassese explains why this was not the case. Using data from the American National Election Study, she finds that Republican women are much closer to Republican men than Democratic men or women on every issue but gun control. Republican women, she writes, are just as ideologically extreme as Republican men, and will vote for their party’s candidate regardless of policy appeals or accusations of sexism.

Throughout the 2016 election, many analysts speculated that Donald Trump would face the largest gender gap in American history. They cited his ongoing feuds with female celebrities and journalists, attacks on his rival, Democrat Hillary Clinton for playing the woman card, and lukewarm support from Republican women in polls as evidence of his “woman” problem. Many were convinced that the Access Hollywood tapes would cement his fate among women voters. While a large gender gap did emerge, with exit polling pointing to a 13 percent gender gap among Hillary Clinton voters, Clinton didn’t carry all women – 52 percent of white women voted for Trump and he won handily among women without college degrees. Ultimately, party carried the day with 88 percent of Republican women voting from Trump, compared to 89 percent of Republican men.

Why didn’t women rush to support Clinton? In new research, coauthored with Tiffany D. Barnes, we offer some insight into what happened on Election Day. We investigated gender differences within the Republican Party in order to better understand Republican women’s political thinking and behavior. Using data from the 2012 American National Election Study, a nationally-representative survey conducted during the last Presidential contest, we charted attitudes toward ten policy areas by gender and party to visualize gender gaps in the American electorate. The policy areas reflect answers to survey questions, which were put on a common scale for comparison purposes, with negative scores corresponding to liberal positions and positive scores corresponding to conservative positions. Moderate positions have a score of zero. The mean issue position is plotted and include a confidence interval to illustrate where group differences are statistically significant.

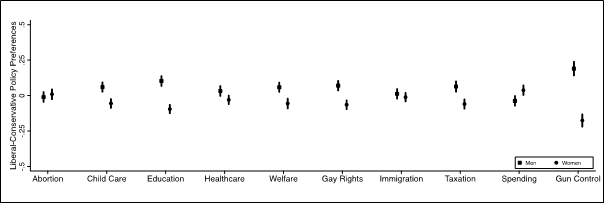

Figure 1 shows the average gender gap, with women holding more liberal positions than men on a variety of policy areas. The gender gap is apparent for many policies typically thought of as “women’s issues,” including childcare, education, social welfare, and gun control. Most of the political science literature focuses on these average differences between men and women, posing explanations for women’s greater liberalism tied to gender differences in socialization, women’s shared experiences as mothers, or women’s greater economic vulnerability. These theoretical perspectives may account for some of the average differences between men and women, but they don’t address women’s attraction to the Republican Party or offer much insight into Republican women’s voting behavior in 2016.

Figure 1 – Party preferences among Men and Women

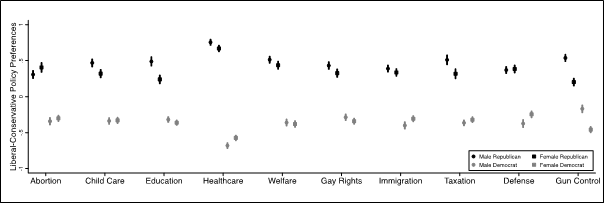

The conventional wisdom that women are more liberal than men, particularly on women’s issues, led to the assumption that Trump’s comments would further polarize women voters. Looking at the intersection of gender and party in Figure 2 is instructive in that it highlights the conservatism of Republican women. Republican women are much closer to Republican men on nearly every issue area than they are to Democratic men or women. The only exception is gun control, for which Republican women hold a policy preference that is equidistant from Republican men and Democratic men.

The primary story emerging from this figure is one of partisan polarization. Differences in policy attitudes based on party are stark and swamp differences based on gender. But that’s not to say that gender doesn’t matter. Looking within the parties, one can see small but statistically significant differences between men and women – particularly among Republicans. For six of the ten policy areas, Republican women are more moderate than Republican men. Differences among Democrats are much more modest, and the inclusion of statistical controls virtually eliminates the gender gaps among Democrats. Republican gender gaps persist however, meaning that we can be confident these differences are due to gender and not some other unmeasured characteristic of the voters. In some additional analysis (not pictured here) we even see these differences among male and female Republican primary voters – a group thought to have the highest level of partisan polarization.

Figure 2 – Policy preferences by Party and Gender

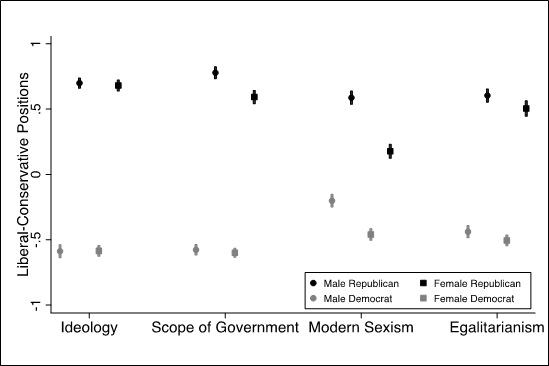

What explains these differences between Republican men and women? We dug into the origins of the Republican gender gaps and found that modern sexism – a belief that gender-based inequality is due to women’s personal choices rather than systematic discrimination – offers a lot of explanatory power. Gender and party differences in modern sexism are charted below, along with three additional factors we explored in our analysis. Republican women score significantly higher on modern sexism than both male and female Democrats, though they score lower than male Republicans. This finding is instructive in light of Trump’s alleged “women problem,” in that Republican women may have been less likely than Democrats to situate his comments in terms of a broader systems of discrimination. While modern sexism influences policy attitudes for Republican women, they are just as ideologically extreme as Republican men and just at likely to demonstrate partisan loyalty at the polls.

Figure 3 – Political Orientations and values by party and gender

Note: Egalitarianism is reversed here, such that high scores correspond to anti-egalitarian positions. High scores reflect conservative viewpoints on all four values and political orientations.

Judging from these figures, it’s clear that there was a wide chasm Republican women needed to cross to in order to cast their votes for Clinton. Most didn’t cross it. Republican women are more moderate than Republican men, but probably not moderate enough to have felt a tug from the Clinton campaign. The results suggest that female voters are unlikely to cross party lines to vote for women candidates – neither policy appeals nor accusations of sexism were strong enough forces to overcome partisan polarization.

This post is based on the paper “American Party Women: A Look at the Gender Gap within Parties” which appeared in Political Research Quarterly and was written with Tiffany D. Barnes.

Featured image credit: Mark Mathosian (Flickr, CC-BY-NC-SA-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2kwrpbw

______________________

Erin C. Cassese – West Virginia University

Erin C. Cassese – West Virginia University

Erin C. Cassese is an Associate Professor of Political Science at West Virginia University. Her research on gender and race in American Politics has appeared in Politics & Gender, Legislative Studies Quarterly, The Journal of Politics, Sex Roles, and PS: Political Science & Policy, among other peer-reviewed outlets.