There are now more than 3,000 drug courts in the US, which aim to promote treatment rather than punishment for nonviolent offenders. While drug courts have been found to be effective in reducing drug use for participants in general, there is less evidence of how well they work for certain groups. In new research Kelly Frailing examines the effectiveness of a drug court for Hispanic participants, finding that the ability to speak Spanish with the judge was rated very highly in terms of services offered by the court.

There are now more than 3,000 drug courts in the US, which aim to promote treatment rather than punishment for nonviolent offenders. While drug courts have been found to be effective in reducing drug use for participants in general, there is less evidence of how well they work for certain groups. In new research Kelly Frailing examines the effectiveness of a drug court for Hispanic participants, finding that the ability to speak Spanish with the judge was rated very highly in terms of services offered by the court.

Drug courts are a type of specialty or problem solving court that are designed to provide nonviolent drug offenders with treatment instead of punishment. The idea is that treating the problem of drug abuse will reduce or even eliminate future contact with the criminal justice system. Drug courts have proliferated since the first was established in Miami in 1989; as of 2015, there were over 3,100 drug courts in the United States.

Many studies have found that drug courts are effective at reducing criminal justice system involvement; and that they are effective at reducing drug use for participants. However, it remains unclear if drug courts work equally well for everyone. For example, research has found that drug courts are less likely to produce reductions in crime and in drug use for African American participants. Even less is known about how well drug courts work for Hispanic participants.

My collaborator Diana Carreon and I became curious about whether there were unique features of drug courts with a majority of Hispanic participants after we observed a number of sessions at the drug court in Laredo, Texas. The drug court in the border town of Laredo serves an almost entirely Hispanic and almost entirely bilingual participant group and has a bilingual judge. In these sessions, we observed the participants and the judge using both English and Spanish during their interactions, with just under half the interactions containing at least some Spanish. We hypothesized that the ability to interact with the drug court judge in Spanish when desired was an important feature of the drug court for these participants.

With that in mind, we modified the survey utilized in the Multi Site Adult Drug Court Evaluation (MADCE) for the drug court in Laredo. The MADCE survey was designed to discover perceptions of procedural justice through questions about the judge, about participants’ voice in the process, participants’ understanding of the drug court process, about fairness and about dignity. We added a question about whether the judge spoke Spanish with the participants when they wanted or needed to.

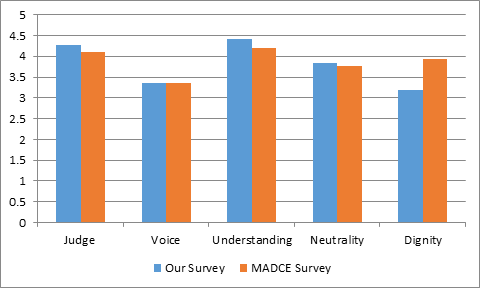

We offered our modified survey to all participants in the Laredo drug court and just over a third of them completed the survey; importantly, we offered the survey in English and Spanish. We compared our results to the survey results of the participants in the MADCE study and this comparison appears in Figure 1.

Figure 1 – Perceptions of procedural justice by survey

Note: On a scale of 1 to 5 where 1 is the most negative and 5 is the most positive perception

From Figure 1, it is clear that those who completed the survey in the Laredo drug court had more positive perceptions of the judge, of voice in the process, of understanding and of fairness; the only aspect of procedural justice that those who completed the MADCE survey rated higher than the participants in the Laredo drug court was dignity. Because we were specifically interested in how the ability to speak Spanish with the judge when desired impacted participants’ perceptions of the drug court, we disaggregated the survey results by each aspect of procedural justice. These results are show in Table 2:

| The judge... | Mean response | Procedural justice | Mean response |

|---|---|---|---|

| Is knowledgeable about your case | 4.26 | You are able to express your views in the drug court sessions (voice) | 4.25 |

| Knows you by name | 4.16 | You are too intimidated or scared to express your views in drug court (voice) | 2.13 |

| Helps you succeed | 4.38 | You have influence over what is decided in drug court (voice) | 3.47 |

| Emphasizes the importance of drug treatment | 4.53 | You have enough control over the way things go in drug court (voice) | 3.63 |

| Is intimidating and unapprochable | 2.41 | You understand what happens during drug court (understanding) | 4.41 |

| Remembers your situation and needs from session to session | 4.09 | You understand what your rights are during drug court (understanding) | 4.41 |

| Gives you a chance to tell your side of the story | 4.53 | You feel the people who did the same things as you were treated the same way in drug court (neutrality) | 3.84 |

| Can be trusted to treat you fairly | 4.5 | You feel pushed around during drug court (dignity) | 2.09 |

| Treats you with respect | 4.66 | You are treated unfairly by the drug court (dignity) | 1.87 |

| Communicates with you clearly | 4.66 | People in the drug court are polite to you (dignity) | 4.28 |

| Speaks Spanish with you when you want/need to | 4.56 | You are treated with respect in drug court (dignity) | 4.53 |

| Listens and takes into account your input | 4.53 |

Note: On a scale of 1 to 5 where 1 is the most negative and 5 is the most positive perception

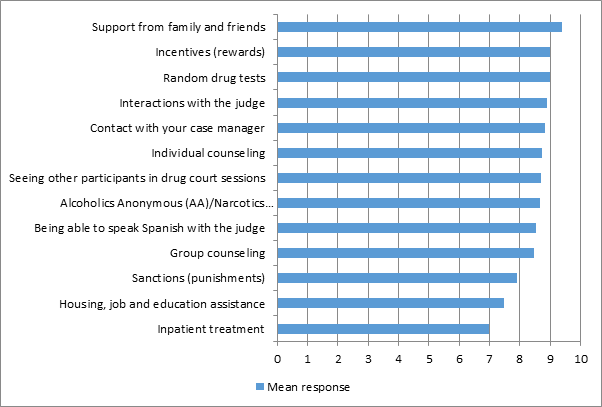

From Table 2, it is clear that the ability to speak Spanish with the judge is rated very positively by participants in the Laredo drug court. It is among the most highly rated features of the judge, third only to the judge treating participants with respect and to the judge communicating clearly with participants. Moreover, being able to speak Spanish with the judge when desired is rated more highly than any of the measures of procedural justice. Because we were also interested if participants viewed the ability to speak Spanish with the judge when desired as a helpful service offered by the drug court and not just as a feature of the judge, we added a set of questions about how helpful each individual service provided by the drug court was. These results appear in Figure 3.

Figure 2 – How helpful to your success in the drug court is the following?

Note: On a scale of 1 to 10 where 1 very unhelpful and 10 is very helpful

From Figure 2, it is clear that Laredo drug court participants’ rate being able to speak Spanish with the judge as just the eighth most helpful of the thirteen services on the survey. However, there was only a one point difference between it and the highest rated service, support from family and friends, and only a half point difference between it and the highest rated services offered by the drug court, random drug tests and incentives.

When we examined the results seen in Table 2 and Figure 2 together, a more nuanced picture began to emerge. For example, when participants were asked about the ability to speak Spanish with the judge as a feature of the judge (Table 2), we observed that about 70 percent of participants rated this item a 5 and that only two of these ratings of 5 came from Spanish language rather than English language surveys. And when participants were asked about the ability to speak Spanish with the judge as a service (Figure 2), about two thirds of participants rated this item a 10 and only two of these ratings of 10 came from Spanish language rather than English language surveys. In sum, whether the ability to speak Spanish with the judge is framed as a quality of the judge or as a service of the court and whether the participants prefer English or Spanish, it is clear that participants at the Laredo drug court perceive this ability as important and helpful to their success.

These results have important policy implications for future drug courts. As the Hispanic population of the United States continues to increase and as drug court best practices include the provision of more drug courts to historically disadvantaged groups, it is important that careful consideration be given to the language abilities of the judges who choose or who are chosen to preside over majority Hispanic drug courts.

This article is based on the paper ‘Quiero Hablar Con Usted en Espanol, Juez: The Importance of Spanish at a Majority Hispanic Drug Court’ in Criminal Justice Policy Review.

Featured image credit: Brent Moore (Flickr, CC-BY-NC-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2lcPDfc

______________________

Kelly Frailing – Loyola University New Orleans

Kelly Frailing – Loyola University New Orleans

Dr. Kelly Frailing is an Assistant Professor of Criminology and Justice at Loyola University New Orleans. Her two main research interests are offenders with mental illness and crime and disaster. She is most recently the co-author of Toward a Criminology of Disaster (in production with Palgrave Macmillan) as well as the co-author of the second edition of Fundamentals of Criminology: New Dimensions and the co-editor of the third edition of Crime and Criminal Justice in Disaster (both with Carolina Academic Press).