Gentrification has been long thought to be sparked by artists and artistic businesses that move into poorer areas. But new research from Carl Grodach, Nicole Foster, and James Murdoch finds that we need to rewrite the story of arts-led gentrification. In a study of the 30 largest US metros, they find that art industries generally do not cause gentrification and the associated displacement of poorer residents. In fact, gentrified places tend to attract the arts, the reverse of the traditionally assumed relationship.

Gentrification has been long thought to be sparked by artists and artistic businesses that move into poorer areas. But new research from Carl Grodach, Nicole Foster, and James Murdoch finds that we need to rewrite the story of arts-led gentrification. In a study of the 30 largest US metros, they find that art industries generally do not cause gentrification and the associated displacement of poorer residents. In fact, gentrified places tend to attract the arts, the reverse of the traditionally assumed relationship.

Experts have long claimed that the arts fuel gentrification– the process by which neighborhoods suffering from declining investment experience an influx of capital and middle and upper class residents. The common storyline is that artists and artistic businesses move to a neglected neighborhood and set the stage for gentrification by renovating and repurposing its aging buildings. Higher income groups, attracted to neighborhoods flush with spaces for cultural consumption, bid up rents, create social tensions and potentially displace long-time residents and businesses, not to mention artists. This scenario has certainly played out in some places– think SoHo or Chelsea in New York, or Silver Lake and most recently Boyle Heights in Los Angeles. However, as our recent study shows, this narrative oversimplifies the relationship between the arts and neighborhood change across varied contexts.

To better understand the relationship between the arts, gentrification, and displacement we examined neighborhood-level arts industry activity in the 30 largest US metros with populations of over 2,000,000 between 2000 and 2013.We also honed in on patterns in four large regions— Chicago, Dallas, Los Angeles, and New York. We studied two types of art industries— the fine arts (theatre and performing arts companies, museums, art galleries, independent artists and fine arts schools) and commercial arts (film, music and design-related industries). A detailed explanation of data and methods is available in the full study.

We find that the arts have multiple, even conflicting relationships with gentrification and displacement. While the presence of commercial arts establishments increases the likelihood that a neighborhood experiences gentrification, the fine arts do not. Furthermore, neither commercial arts nor fine arts are associated with displacement. Rather, we find the accepted arts-gentrification relationship turned on its head. Instead of descending on neighborhoods with cheap rent and sparking gentrification, many artists and artistic businesses actually seek out already gentrified areas. The exception to this rule occurs in neighborhoods with 1) a high concentration of arts activity in regions with below average concentrations of arts establishments and 2) where gentrification is not widespread. These findings provide an important corrective to the notion that the arts cause gentrification and displacement. Neighborhood change is more likely due to other complex factors.

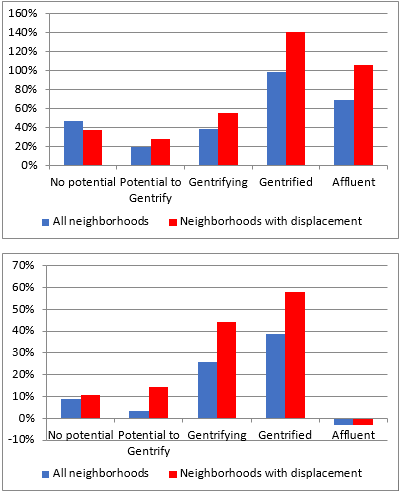

We first categorize neighborhoods by their potential to gentrify as well as whether the neighborhood experienced any indications of gentrification and displacement over time. We then determine where arts industries locate. Contrary to expectations, fine and commercial arts establishments are least common in gentrifying neighborhoods and those with the potential to gentrify (Figure 1). The commercial arts are most concentrated in areas that gentrified, while the fine arts tend to prefer affluent neighborhoods. Both art clusters are also common in places we classify as having no potential to gentrify – neighborhoods that are well-off but not quite affluent. However, the fine arts are nearly four times more concentrated in higher income areas with signs of displacement than in those without. In other words, the highest concentrations of arts establishments are in places that are already wealthy and becoming increasingly segregated by wealth.

Figure 1 – Average number of Fine art and Commercial art establishments by neighborhood type, 2000.

By contrast, the fine arts and commercial arts exhibit sizable growth in places that are gentrifying. Commercial arts growth is still strongest in gentrified areas while fine arts growth is also robust in affluent areas. Further, growth rates are highest in the more upscale neighborhoods where displacement occurred (Fig. 2). This indicates that the fine arts are attracted to higher rent markets or that initial arts establishments are replaced by more upscale arts at a faster rate over the study period. The commercial arts show a similar pattern with one key difference– they are on the decline in affluent neighborhoods. This potentially indicates that commercial arts establishments leave affluent areas and contribute to the rapid upscaling of gentrified places.

Figure 2- Average percent growth of fine arts establishments (top) and commercial arts establishments (bottom) by neighborhood type, 2000-2013

Based on these results, however, we cannot say whether the arts drive gentrification and displacement or if they are attracted to more upscale areas where displacement might occur. Therefore, we conduct a statistical analysis that controls for neighborhood conditions to better determine how the arts impact gentrification and displacement.

Our regression models confirm that arts industries do not uniformly cause gentrification and displacement; while the presence of commercial arts establishments increases the likelihood of gentrification, this relationship does not hold for the fine arts. The results also confirm that neither the fine arts nor commercial arts have a significant relationship with displacement. Most interestingly, our model indicates that gentrification leads to the growth of fine and commercial arts establishments. In other words, while arts growth does occur in the context of gentrification, the arts are not driving that relationship; gentrified places are attracting the arts.

Finally, we determine whether these relationships persist across different regional contexts by focusing on Chicago, Dallas, Los Angeles and New York. Results for these four metros reinforce the findings from the full metro analysis with an important exception. An arts industry presence predicts gentrification in Chicago and Dallas, but not in Los Angeles and New York, as we would expect. This highlights that the arts-gentrification link is strongest in cities, like Chicago and especially Dallas, where arts and gentrification dynamics are concentrated in fewer areas. In contrast, in Los Angeles and New York, where the arts are more dispersed throughout different types of neighborhoods, gentrification is driven predominately by other factors. In other words, the familiar arts-led gentrification relationship is most likely found in metros where the arts and gentrification are less prevalent overall. These cities, unlike the largest, most expensive metros, contain a more concentrated and limited number of gentrified places, thus magnifying the arts-gentrification effect. As such, it is not simply the presence of arts activity in combination with a competitive real estate market that explains arts-related gentrification, as commonly accepted.

These results have important implications for how we study the role of the arts in neighborhood change and for how governments approach the arts and creative industries in urban policy. Given that art establishments cluster amongst linked industries and their customer base, it is folly to pursue policies that incentivize new artistic activity assuming that it will spark development, especially in economically modest areas. However, it is also less likely that arts-led strategies will engender gentrification and displacement there. The caveat to this is that regions with a lower density of arts activity overall are more likely to experience arts-related gentrification in those few places where the arts concentrate. In such instances, policy must attend to mitigating potential displacement pressures.

The research was supported by a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts. Grant No. 12-3800-7004. This article is based on the paper, ‘Gentrification, displacement and the arts: Untangling the relationship between arts industries and place change’ in Urban Studies.

Featured image credit: Kat Northern Lights Man (Flickr, CC-BY-NC-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2lh2Jrc

_________________________________

Carl Grodach – Queensland University of Technology

Carl Grodach – Queensland University of Technology

Carl Grodach is a Senior Lecturer at Queensland University of Technology (QUT) in Brisbane, Australia. His research focuses on the urban development impacts of arts organizations, cultural industries, and cultural policy. His books include The Politics of Urban Cultural Policy: Global Perspectives (Routledge, 2013) and Urban Revitalization: Remaking Cities in a Changing World (Routledge, 2015).

Nicole Foster – University of Texas at Arlington

Nicole Foster – University of Texas at Arlington

Nicole Foster is adjunct Assistant Professor for the College of Architecture, Planning, and Public Administration at the University of Texas at Arlington. She researches the relationship between the built environment, aesthetics, and affect and its impact on collective efficacy and neighborhood vitality.

James Murdoch – 2M Research Services

James Murdoch – 2M Research Services

James Murdoch is a Policy Analyst with 2M Research Services. His research experience includes work supported by a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts examining the relationship of arts and cultural industries to economic development and neighborhood gentrification, as well as work on an international data set of cultural amenities with information on over 10 countries.

1 Comments