The vast majority of the members of both houses of Congress tend to win reelection when they stand. But what about retirement? While House Republicans tend to retire at higher rates than their Democratic counterparts, this does not hold for the Senate. Theodore J. Masthay and L. Marvin Overby find that Republican and Democratic Senators retire at very similar rates, likely because they face a less arduous campaign schedule compared to those in the House, the power that the Senate gives them, and the extreme seniority of the office.

The vast majority of the members of both houses of Congress tend to win reelection when they stand. But what about retirement? While House Republicans tend to retire at higher rates than their Democratic counterparts, this does not hold for the Senate. Theodore J. Masthay and L. Marvin Overby find that Republican and Democratic Senators retire at very similar rates, likely because they face a less arduous campaign schedule compared to those in the House, the power that the Senate gives them, and the extreme seniority of the office.

There are three ways for legislators to leave office: electoral defeat, retirement (either from public life or to pursue another office), and death. While electoral defeats are a significant source of legislative turnover, in the US Congress in recent years they have been far outstripped by retirements (as Figure 1 shows). However, the scholarly attention paid to legislative retirements in the United States has almost exclusively been centered on the House of Representatives. The Senate offers an interesting case to test the institutional and partisan differences between the two houses of Congress.

The prevailing wisdom about the careers of members of Congress suggests that their tenures resemble something akin to lifetime appointments. This belief is not entirely without merit, considering the remarkably high reelection rates of those members, which hovers around 90-95 percent for those serving in the House of Representatives and 80-85 percent for Senators. Since electoral defeats are relatively rare, the dynamics of legislative retirements should receive more attention than they have.

Figure 1 – Sources of Legislative Turnover: Retirements vs. Electoral Defeats

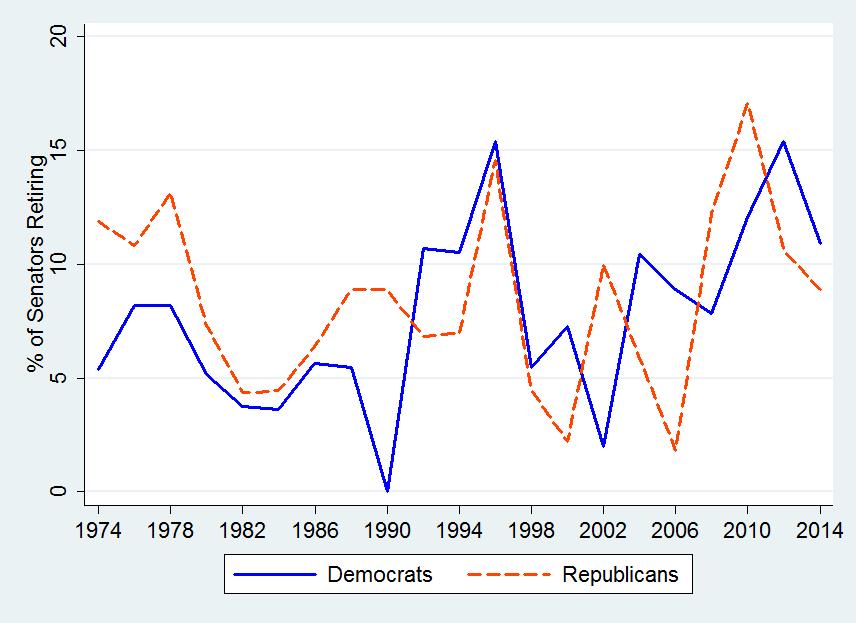

Research on retirements from the House of Representatives has shown a consistent tendency for Republican legislators to retire at higher rates than their Democratic colleagues. Our research shows that the same is not true in the upper chamber. Rather, as Figure 2 illustrates, Republican and Democratic Senators retire at remarkably similar rates, suggesting underlying differences between the chambers and the parties.

Figure 2– US Senate Retirement Rates by Party

We think these differences relate to the levels of enjoyment Republicans experience in the respective chambers. As the party of limited government, Republicans typically do not approve of large scale government activity and the catering to special interests seeking government support that typifies the work of most House members. Historically, this has led rather large numbers of House Republicans to voluntarily leave office either to return to the private sector or pursue other, more amenable offices.

Why are GOP senators fonder of their jobs than GOP House members? We think four features that distinguish the chambers help answer that question.

First, the Senate campaign schedule is less arduous than in the House. The six year terms afforded to senators eliminates the “permanent campaign” aspect of serving in Congress that exists in the lower chamber. This ultimately gives senators more freedom to pursue their own legislative interests with a less intense fear of electoral retribution. If, as a matter of partisan culture, you are not all that excited about government service in the first place, the constant campaign that characterizes life in the House may appear especially onerous.

Second, as a majoritarian institution, the House (usually) runs in a relatively regimented fashion, processing the bills that are on the majority’s agenda. In contrast, the Senate uniquely accords individual members immense power through the threatened and actual use of the filibuster and the legislative “hold.” Importantly, the filibuster is a largely negative tool, which prevents rather than furthers the passage of legislation. This almost certainly makes the Senate a more rewarding institution for the “anti-government” party.

Third, in the House, most members truly are backbenchers, with little say in the running of the chamber or the making of policy. Senators, on the other hand, may be more reasonably able to see themselves as “executives” since they share such powers with the president as the confirmation of presidential nominations and treaty ratification. For Republicans, drawn disproportionately from the upper reaches of the private sector and more likely to think of themselves as CEO material, the executive functions shared by senators – along with the generally higher status of being one of 100 rather than of 435 – must make the Senate a more attractive option.

Fourth, for reasons outlined above, a good number of Republicans cut short their service in the House to run for the Senate (and for governorships, where they can indulge more of their states’ rights ideologies), but there are a dearth of offices that can be classified as higher than a seat in the Senate. In fact, only one position, the presidency, can be definitively described as such. While historically there have been a non-trivial number of senators who have retired from the body to become vice presidents, governors, and cabinet level officials, each one of those moves could be described as lateral. In fact, only three senators (and only one GOP senator: Warren Harding) have been elected directly to the presidency from the Senate. In short, for progressively ambitious Republican senators, the Senate represents the ultimate realistic office.

Our research concludes that age and being in the minority party affect Senate retirements in predictably positive ways and that prior legislative experience has a negative effect. However, our main contribution is to highlight that the institutional differences between the House of Representatives and the Senate are important enough to affect the retirement decisions of their members. Simply put, the Senate is a more desirable place to serve than the House in general, and for Republicans in particular. While retirements are but one of many factors that contribute to the overall partisan balance in Congress and the effects of retirements can be obscured by other relevant factors, they have implications for which party controls which chamber. Everything else equal, our research indicates that Republicans are better situated to a majority in the Senate than in the House, since by their retirement decisions they surrender less of the incumbency advantage in the upper chamber.7

This article is based on the paper, ‘Dynamics of Senate Retirements’, in Political Research Quarterly.

Featured image: “Orrin Hatch (R-Utah) and Dave Camp (R-Michigan)” by Michael Jolley is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2opF0nU

_________________________________

Theodore J. Masthay – University of Missouri

Theodore J. Masthay – University of Missouri

Theodore J. Masthay is a Ph.D candidate in the Department of Political Science at the University of Missouri. His research focuses on legislative careers, with interest paid to the ways career trajectories diverge based on party, and how institutional differences both domestically and abroad affect career decisions.

L.Marvin Overby – University of Missouri

L.Marvin Overby – University of Missouri

L. Marvin Overby is professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Missouri. In addition to legislative careers, his research interests include legislative rules and procedures (such as the discharge petition in the U. S. House of Representative, the filibuster in the Senate, and free votes in various parliamentary settings), minority politics, and Southern politics.