Using data from Gallup Poll’s “most important problem” question from 1969 to 2012 Melinda R. Tarsi, Jesse H. Rhodes, and Tatishe M. Nteta were able to evaluate whether Presidents addressed issues of importance to African Americans when delivering speeches to the public. Despite views held by many that Obama failed to represent black interests while in the White House, research found that he was the lone president to prioritize black issues over white issues in his major speeches.

Using data from Gallup Poll’s “most important problem” question from 1969 to 2012 Melinda R. Tarsi, Jesse H. Rhodes, and Tatishe M. Nteta were able to evaluate whether Presidents addressed issues of importance to African Americans when delivering speeches to the public. Despite views held by many that Obama failed to represent black interests while in the White House, research found that he was the lone president to prioritize black issues over white issues in his major speeches.

In the waning weeks of the 2016 presidential campaign, then-candidate Donald Trump made a concerted effort to mobilize African American voters. In speech after speech, Trump outlined a litany of problems facing the African American community from rising crime rates to failings schools, attributed these problems to a lack of decisive leadership by the Democratic Party, and asked the black community a simple question as it pertained to voting for Trump; “What do you have to lose?” Despite Trump’s history of discrimination against African Americans, his strategy seemingly paid off, garnering him garnered 8% of the African American vote (compared to the 4% given to John McCain in 2004 and the 7% allocated to Mitt Romney in 2012).

At the heart of Trump’s somewhat successful appeal to African Americans is the belief that the Democratic Party, and more specifically former President Barack Obama, failed to deliver on campaign promises to the African American community. Indeed, a number of prominent African American intellectuals and political leaders have called Obama to task for his inability to adequately represent the interests of African Americans and for his reluctance to seek policy solutions to the myriad of socioeconomic and political problems that continue to vex the black community.

While the belief that Obama failed to represent black interests while in the White House has become a familiar trope in retrospectives on his presidency, there is surprisingly little in the way of empirical explorations of Obama’s representation of African American interests. We address this shortcoming in our recently published paper entitled, “Conditional Representation: Presidential Rhetoric, Public Opinion, and the Representation of African American Interests.” In this research, we investigate whether issues of import to African Americans were addressed by American presidents in their major speeches to the nation or if presidents were more likely to represent the concerns of white Americans in their speeches.

Methodology

To establish how well presidents represented the interests of Whites and African Americans, we first created a dataset using the Gallup Poll’s “most important problem” question from 1969 to 2012. This survey question asked respondents about the issue that they thought was the most pressing to the country. Using this question, we placed each unique answer to the question under a broad set of ten categories that included: government institutions and processes; economic inequality and civil rights; moral and religious issues; social welfare; macro-economic issues and problems; pocketbook economic issues and problems; national security; international affairs; energy and the environment; and other government issues.

With this information, we were able to uncover the set of broad issues that were deemed most important by African Americans and Whites in each calendar year. To determine presidential priorities, we collected and analyzed all of the “major” speeches of the President during that same time period. Each of the speeches in our dataset was a high-focus, public address – one in which the President was speaking to the entire nation as opposed to groups legislators or lobbyists. Our analysis covered every president between Richard Nixon and Barack Obama.

Using computer analysis, we first developed a concordance of every unique word found in our major address dataset. We manually examined every unique word, allocating relevant words with one of the basic issue categories described above. For example, words like “jobs”, “inflation”, and “recession”, were associated with ‘Pocketbook economic issues and problems’, while “terrorism”, “nuclear”, and “war” were associated with ‘National security’ category. Next, we investigated the frequency with which each president used keywords associated with each of the categories per 1,000 words of their major addresses. By combining the ‘most important problem’ data with the presidential priorities data, we were able to assess how well presidential priorities reflected those of African Americans and Whites, respectively.

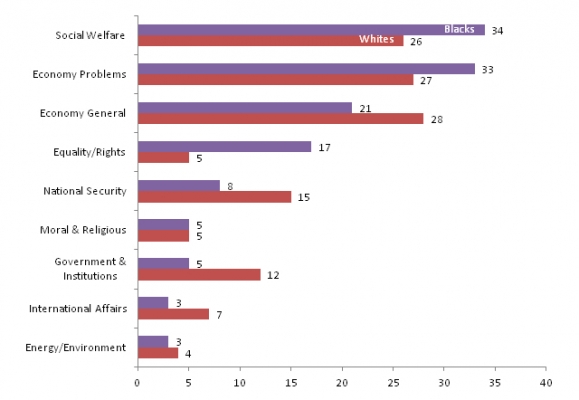

The data revealed several important patterns. First, contrary to the belief that blacks and whites hold divergent policy positions, we found significant overlap between the issues that black and white Americans viewed as the most important. More precisely, we find that both groups consistently identified the same three types of issues – ‘Social welfare’, ‘Macro-economic issues and problems’, and ‘pocketbook economic issues and problems’ – as the most important problems facing the nation between the years 1969 and 2012.

Figure 1 – Number of Years Issue Was In the Top Three Concerns by Race, 1969-2012

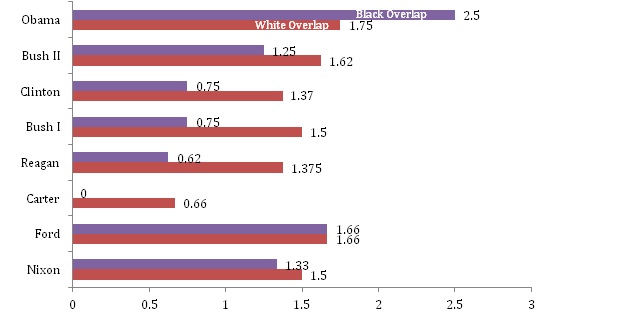

Over the 44 years analyzed, presidents were indeed more likely to address Whites’ most important issues in their addresses. However, as the first black president, did President Obama adhere to this pattern and ignore the issues of import to African Americans during his presidency? In order to address this question, we measured the extent to which presidents since 1968 talked about issues that mattered most to white and black Americans in their public speeches (a statistic we define as “overlap”). Among the eight presidents in our analysis, Obama during his first term in office was the lone president to prioritize black issues over white issues in his major speeches.

Figure 2 – Average Overlap Between Presidential Rhetoric and Citizen Concerns by Race, 1969-2012

Our findings suggest that while presidents generally speak more to issues of concern to white voters than they do to those of black voters, the nation’s first black president did in fact make a concerted effort to publicly speak to issues of import to the African American community. While pundits and public intellectuals may malign Obama’s alleged failure to speak to African American concerns, it is virtually certain that his successor, Donald Trump, will prove much less attentive.

This article is based on the paper “Conditional Representation: Presidential Rhetoric, Public Opinion, and the Representation of African American Interests” in Journal of Race, Ethnicity, and Politics.

“Barack Obama with a crowd in Ottawa 2-19-09” by Pete Souza is licensed under Wikimedia Commons.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2qHUKn0

________________________________

Melinda R. Tarsi – University of Massachusetts Amherst

Melinda R. Tarsi – University of Massachusetts Amherst

Melinda R. Tarsi is Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science and Master of Public Administration Program at Bridgewater State University. She is currently working on her book manuscript entitled, Camouflaged Politics: The G.I. Bill, the Veterans’ Benefit Coalition, and American Higher Education Policy. Her work has been published in Armed Forces and Society, Political Research Quarterly, and Politics, Groups, and Identities.

Jesse H. Rhodes – University of Massachusetts Amherst

Jesse H. Rhodes – University of Massachusetts Amherst

Jesse H. Rhodes is Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. He is the author of Ballot Blocked: The Political Erosion of the Voting Rights Act (Stanford University Press, 2017) and An Education in Politics: The Origin and Evolution of No Child Left Behind (Cornell University Press, 2012), as well as numerous articles that have appeared in Political Behavior, Presidential Studies Quarterly, and Perspectives on Politics.

Tatishe M. Nteta – University of Massachusetts Amherst

Tatishe M. Nteta – University of Massachusetts Amherst

Tatishe M. Nteta is Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. His research is situated within the subfield of American politics and examines the impact that the sociopolitical incorporation of the nation’s minority population has on public opinion, political behavior, and political campaigns. His work has appeared in Political Research Quarterly, Political Psychology, Political Communication, American Politics Research, and Social Science Quarterly.