High rents and house prices across America means that mobile homes are playing an increasing role in providing housing in the US. Mobile homes placed in mobile home parks can be precarious, with the potential for closure at any time, displacing hundreds of residents. Esther Sullivan spent two years conducting ethnographic analyses of mobile home parks in Florida and Texas, two states with very different policies for managing displaced residents. She found that Florida’s more generous, but privately run, regime actually made it more difficult for the displaced to relocate, while in Texas, residents were able to resettle much more quickly, albeit after using up more of their own resources.

High rents and house prices across America means that mobile homes are playing an increasing role in providing housing in the US. Mobile homes placed in mobile home parks can be precarious, with the potential for closure at any time, displacing hundreds of residents. Esther Sullivan spent two years conducting ethnographic analyses of mobile home parks in Florida and Texas, two states with very different policies for managing displaced residents. She found that Florida’s more generous, but privately run, regime actually made it more difficult for the displaced to relocate, while in Texas, residents were able to resettle much more quickly, albeit after using up more of their own resources.

At a time when 1) the cost of entry-level homes is once again rising in most US metro areas and 2) an individual working full time for minimum wage cannot afford rent for a fair-market one bedroom unit in any US state, the mobile home is filing the gap between housing needs and housing opportunities for about 8.4 million US households. In fact, manufactured housing – more often called mobile homes or trailers – is the country’s single largest source of unsubsidized affordable housing.

Mobile homes often provide the only access to the American Dream of homeownership for low-income households. In 2011, they accounted for 30 percent of all new homes sold under $200,000, 50 percent of all new homes sold under $150,000, and 71 percent of all new homes sold under $125,000.

About one third of mobile homes are located in mobile home parks, where residents own their homes but rent the land under their homes. While 80 percent of mobile home park residents own their homes only 14 percent of these residents also own the land beneath their homes. This divided land tenure is part of what makes housing in mobile home parks so affordable, but it also makes mobile home parks some of the most insecure communities in the US.

Mobile home parks can, and often do, close at any time and legally evict residents. The vast majority of these residents own their homes and they are forced to move them at their own expense. Over the last four decades, mobile homes have become virtually immobile. They are intended to be transported once – from the factory to the site. Moving these homes costs up to $15,000 and can result in serious structural damage as well as lost value in the home.

“Abandoned Trailer Park” by Matthew Hester is licensed under CC BY 2.0

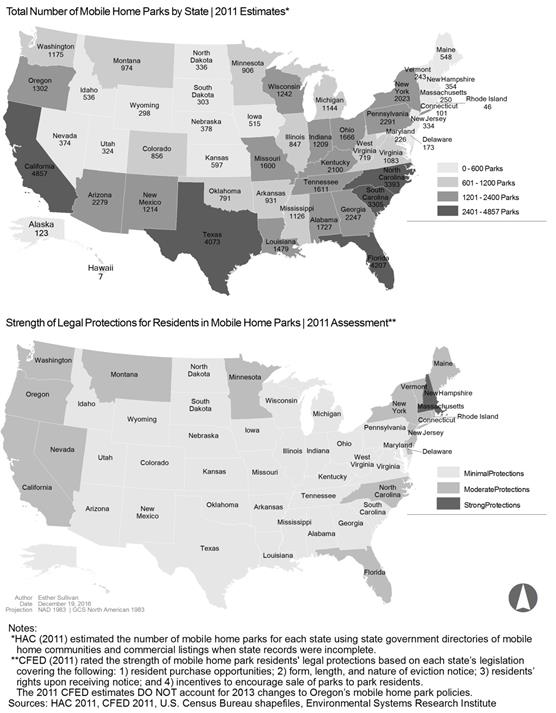

Mobile home parks close frequently and displace entire communities. Park closures present residents with a difficult choice: pay thousands to move the home to a new park if the home is deemed structurally sound for relocation or abandon the home if it is not. Residents make these choices and organize their moves with as little as 30 days’ notice in the many states that lack state policies regarding park closures and relocation. Moreover, many of the states with the largest numbers of mobile homes have the weakest protections for park residents.

Figure 1- Total mobile home parks and tenant protections by State

To understand the experience of eviction in mobile home parks under different state-level housing policies, I conducted two continuous years of ethnographic analysis inside closing mobile home parks in Texas and Florida. Texas and Florida are the two states with the largest mobile home populations. They are also states with different housing policies for managing the relocation of displaced park residents. The primary differences are that Florida statues provide voucherized relocation assistance and a six month notice policy, while Texas statues offers no assistance and mandate only 60 days for nonrenewal of lease.

In both states, I lived inside closing parks and followed residents before, during, and after they were evicted. In total, I had close daily involvement with about 180 residents in the two closing parks where I lived and in 32 surrounding potentially closing parks in both states. To focus on the processes through which mobile home park residents evictions were managed I also shadowed, worked beside, and hauled homes with 12 mobile home movers, installers, and owners of moving companies in both states.

My findings show that in both Florida and Texas, mobile home park closures negatively impacted the living conditions of already impoverished residents. In both states eviction resulted in poorer quality housing alongside additional housing cost burdens after residents moved out of closing parks. For a subset of residents, eviction set off a cycle of housing insecurity as residents bounced between precarious housing situations, homelessness, or doubling up with friends and family.

Moreover, I found that the negative effects of eviction were more complicated and prolonged under Florida’s state regulatory regime, which was paradoxically organized to ameliorate the effects of eviction. While residents in Texas drained entire savings, cut off remittances to family members abroad, and used precious funds from the Earned Income Tax Credit to arrange the relocation of their homes, they were able to exert control over the process. As the sole financier of their moves they were able to dictate the terms and timing of their eviction process. Meanwhile in Florida, the voucherized system of relocation aide created a series of public-private partnerships between the state agency that administers relocation funds and a collection of private moving companies and corporate park communities (where homes were relocated). As the recipient of state funds, moving companies had significant power to dictate the terms and timing of residents’ moves. Florida residents experienced a prolonged and disorienting relocation process that extended for several months (in some cases one year) while Texas residents were able to resettle in their homes in new communities within weeks of a park closure.

Residents in both states would benefit from policy changes in three key areas:

Establishing a minimum six-month eviction notice and directing residents to state-managed relocation support: State regulation of mobile home park closures has been highly effective in states such as Oregon, which recently passed legislation requiring a 365-day eviction notice and relocation fees of $5,000, $7,000, or $9,000 (for an abandoned home, a singlewide, and a doublewide, respectively) paid directly to tenants.

Implementing a mandatory and streamlined inspections process: The cursory post-relocation inspection process in Texas resulted in structural damage and faulty installations, while the lengthy inspection process in Florida greatly extended residents’ dislocation and did not ensure high-quality installations. Proper installation is essential to the continued life of a mobile home and should be a key area of regulation around mobile home park closures

Regulating the marketplace in mobile home relocation aid: Florida’s relocation aid relied heavily on the private sector to convey state-mandated protections, but a lack of oversight allowed private providers to create timelines and conduct practices that maximized profits while extending the trauma of evicted residents. While in Texas a lack of oversight meant residents did not receive their legally entitled eviction notice period; all residents were evicted with 30 days’ notices, though state laws require (but do not enforce) a 60 days’ notice policy. State oversight of existing laws and regulation of for-profit markets in relocation services are essential to ensure equitable relocation procedures.

Promoting legislation to support resident owned communities: The most powerful policy prescription should target the source of mobile home park residents’ housing insecurity rather than its consequence, eviction. Policies that focus only on relocating residents from land-lease park to land-lease parks offer only a band aid solution. Such policies do not target the cause of residents’ housing insecurity and do not sufficiently address the known negative consequences of eviction. Nonprofits such as R.O.C. (Resident Owned Communities) USA, assist residents of closing mobile home parks with collectively purchasing and convert park properties from private ownership to collective ownership, thus guarantee that the lands cannot be sold out from under residents. In July 2017, Rep. Keith Ellison (D-MN) introduced the Frank Adelmann Manufactured Housing Community Sustainability Act (H.R. 3296) to provide a tax credit for property owners to sell park properties to residents or nonprofits. Such legislation would target the root of housing insecurity found in mobile home parks and address the negative impacts of mass eviction documented in this study.

- This article is based on the paper ‘Displaced in Place Manufactured Housing, Mass Eviction, and the Paradox of State Intervention’ in American Sociological Review.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2fWFi6p

_________________________________

Esther Sullivan – University of Colorado Denver

Esther Sullivan – University of Colorado Denver

Esther Sullivan is an Assistant Professor of Sociology at the University of Colorado Denver. Her research focuses on poverty, spatial inequality, legal regulation, housing, and the built environment, with a special interest in both forced and voluntary residential mobility. Her research uses ethnographic methods and geospatial (GIS) analysis.