School districts in the US often have many different types of high schools – some are traditional neighborhood schools, while others are more innovative or focused on behavior or academic remediation. In new research Aaron B. Perzigian, Kemal Afacan, Whitney Justin, and Kimber L. Wilkerson examine the characteristics of students across these school types. They find that African American students, male students, and students with disabilities are overrepresented in behavior–focused schools, a trend which may be linked to poorer outcomes later in life.

School districts in the US often have many different types of high schools – some are traditional neighborhood schools, while others are more innovative or focused on behavior or academic remediation. In new research Aaron B. Perzigian, Kemal Afacan, Whitney Justin, and Kimber L. Wilkerson examine the characteristics of students across these school types. They find that African American students, male students, and students with disabilities are overrepresented in behavior–focused schools, a trend which may be linked to poorer outcomes later in life.

Urban US school districts are made up of diverse high school environments. These include comprehensive neighborhood (traditional) schools and smaller alternative models. Public alternative schools fit into three broad categories: Schools of choice, termed innovative, offer discrete content (e.g., arts or technology) and require potential students to apply to them. These schools may also be associated with innovative teaching philosophies (e.g., Waldorf and Montessori). In contrast, behavior–focused schools target behavior modification and academic remediation schools are locales for students experiencing credit deficiencies. In our research, we analyzed student enrollment distribution across traditional, innovative, behavior–focused, and academic remediation school categories.

Referral and admissions vary by school type. Enrollment for innovative schools is student driven: Students (or families) are responsible for choosing the option and satisfying criteria. Enrollment may be exclusionary for certain groups (e.g., youth experiencing academic difficulty or without prior arts exposure). Admissions requirements may deny access for the very students who might benefit most from these typically more rigorous settings. Conversely, enrollment in behavior–focused schools is determined by school referral, sometimes in collaboration with a student’s family, social worker, probation officer, or juvenile court judge. Academic remediation school enrollment also relies on referral by a student’s neighborhood school. But these are not settings attended by students in trouble for poor behavior; referral is theoretically rooted in academic need.

Reports of educational outcomes per specific types of high schools is sparse. However, some evidence suggests students enrolled in behavior–focused and academic remediation schools have limited academic success. When compared with students in traditional schools, disparate outcomes include lower scores on standardized tests of math and reading, less credits earned, poorer school attendance, and higher dropout rates.

In light of these outcome discrepancies in some alternative models, there is justifiable concern regarding who is educated in these types of schools. To address the question of whether or the proportions of students enrolled different types of secondary schools vary significantly in terms of demographic, socioeconomic, and disability status, we analysed data from over 21,000 students in Grades 9 to 12 in 53 high schools in one large urban district in the Midwestern US.

Underrepresentation in different school types

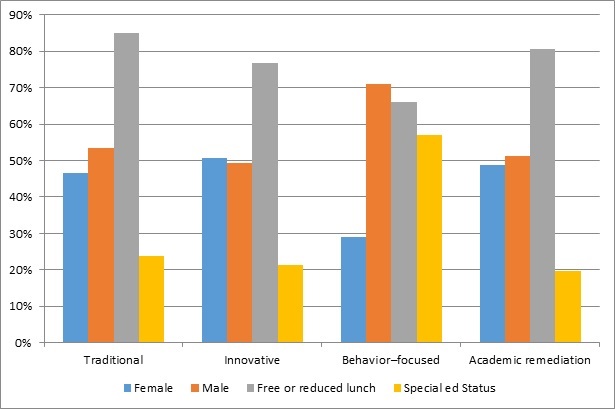

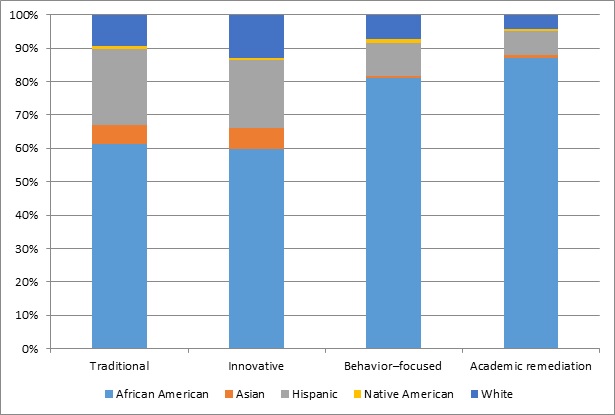

Our findings, shown in Figures 1 and 2, are that there is significant disproportionality within different school types, including overrepresentation of African American students, male students, and students with disabilities in behavior–focused schools; overrepresentation of White students and female students in innovative schools; and underrepresentation of Hispanic and Asian students in academic remediation schools.

Figure 1 – Student characteristics by school type

Figure 2 – Student ethnicity by school type

Note. Special Ed. = students receiving special education services.

Differences in Gender by School Type. Female students attend innovative schools in greater proportion than traditional, behavior–focused, and academic remediation schools. The high proportion of males attending behavior–focused schools is troubling. By attending these schools, students are educated in a nearly all-male environment and surrounded by others deemed problematic. Stigmatization and limited peer access tends to further compound risk for negative outcomes.

Race/Ethnicity Across School Type. African American youth are overrepresented in behavior–focused and academic remediation schools and underrepresented in innovative schools. Hispanic students are significantly underrepresented in all three alternative school models comared to their enrollment in traditional schools.

The overrepresentation of African American students in academically and behaviorally remedial settings, and their underrepresentation in innovative (associated with increased rigor) settings, is concerning and correlates with past research. There is an established body of evidence indicating African American youth are more likely than other groups to be removed from traditional education. Beyond disparate academic outcomes, students relocated to restrictive placements are at increased risk for school disengagement and dropout. Dropping out of school has negative lifelong implications on an individual’s employability, family dynamics, and association with judicial systems such as juvenile corrections or prison.

The overrepresentation of African Americans involved in the US court system is linked to schooling. The trajectory between education and juvenile or adult corrections (i.e., school-to-prison pipeline) is linked to disproportionate and exclusionary discipline procedures toward African American youth. These practices, such as detention and traditional school removal, push students away from their classrooms and into the outer folds of society.

Compared with traditional school proportions, Hispanic youth are underrepresented in innovative, behavior–focused, and academic remediation schools. Asian students are underrepresented in behavior–focused and academic remediation schools as well. If ethnicity plays a role in preventing Hispanic and Asian students from identification for remedial assistance and if an authentic need exists, then underrepresentation in behavior–focused and academic remediation–focused alternative may be a barrier to essential services.

White students are overrepresented in innovative schools, indicating greater access to academic rigor and curricular innovation. Innovative schools tend to provide environments in which critical thinking, self-determination, and community partnerships are emphasized. And these settings often require competitive application to attend (a process associated with capital). It merits questioning the existence of enrollment disparities and reflection on the relationship to postschool outcome gaps.

Greater segregation for disabled students

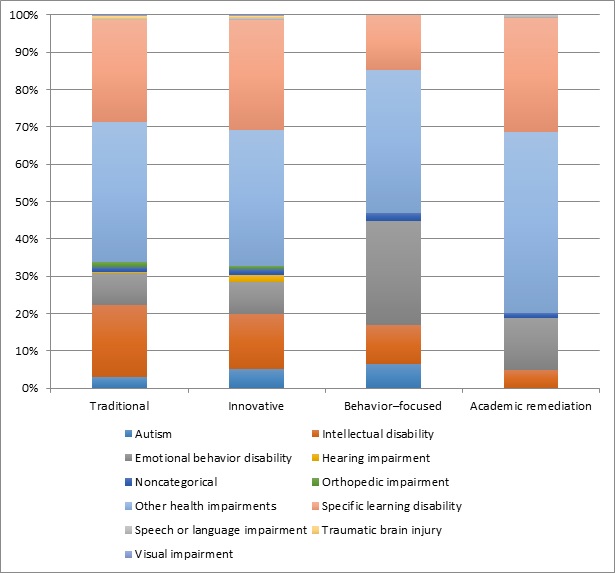

As Figure 3 shows, proportions of disability status are similar between traditional and innovative schools. More than half of students enrolled in behavior–focused schools identified as disabled. Interestingly, academic remediation–focused schools showed the lowest overall proportion. This pattern suggests schools may place students with disabilities in segregated settings more readily when problem behaviors exist—but are less apt to refer students with disabilities to segregated schools focused on academic recovery.

Figure 3 – Disability Categories by School Type

Students with emotional or behavioral disabilities (EBD) are representated highest in behavior–focused schools. This leads us to inquire whether students with EBD labels are adequately served in traditional schools. The distribution of EBD is also significantly high in academic remediation schools, underscoring the relationship between academic and behavioral difficulty. Locales in which youth with disabilities are educated (e.g., separate classrooms or schools), can have profound impact on those students’ schooling and postschool trajectories. Placement in separate primary and secondary environments increases the risk for segregation or restriction in adulthood. Districts should be cautious to minimize the further marginalization of youth with disabilities by relocation to isolated school programs.

More scrutiny of enrollment distribution is needed

Outcome accountability necessitates more critical attention toward enrollment distribution. Variation in academic and social contexts needs to be scrutinized if we are to truly provide equitable opportunities for all youth.

Our study reveals significant demographic differences between students who attend four types of high schools. These enrollment distributions suggest that subgroups of students are referred to or choose to attend alternative schools disproportionately. Overrepresentation of African American and White students in differing school types can be pathways to disparate opportunities. For example, behavior-focused and remedial schools are associated with lower expectations and quick-fix credit recovery—these are the settings in which African American students are overrepresented. White students are underrepresented in them.

Conversely, White students are overrepresented in innovative schools, which tend to provide an enriched learning environment. The disparity of special education status across some school types implies disproportionate removal from traditional education for students with with certain disabilities. These patterns suggest inequitable access to specific educational opportunities for different groups of students. One might consider this phenomenon to mirror the societal inequalities confronting youth and adults in their communities across the nation.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Characteristics of students in traditional versus alternative high schools: A cross sectional analysis of enrollment in one urban district’ in Education and Urban Society.

- Featured image: “2017/365/215 Lockers.” by Ken Bauer is licensed under CC BY NC SA 2.0.

- Please read our comments policy before commenting.

- Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

- Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2gSD0lK

_________________________________________

About the authors

Aaron B. Perzigian – Western Washington University

Aaron B. Perzigian – Western Washington University

Aaron B. Perzigian is an assistant professor in the Department of Special Education and Education Leadership at Western Washington University, in Bellingham, Washington. He is a former special education teacher with experience in behavior–focused schools and residential treatment centers. His research interests include alternative education and social-emotional experiences of students with disabilities.

Kemal Afacan – University of Wisconsin-Madison

Kemal Afacan – University of Wisconsin-Madison

Kemal Afacan is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Rehabilitation Psychology and Special Education at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He completed his master’s degree in Special Education from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He is a former special education teacher who worked at an alternative school serving students with disabilities. His research interests include alternative schools and reading instruction for students with intellectual disability.

Whitney Justin – Madison Metropolitan School District

Whitney Justin – Madison Metropolitan School District

Whitney Justin is currently a special education teacher in the Madison Metropolitan School District, in Madison, Wisconsin. During this study, she was completing her master’s of science degree in special education at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

Kimber L. Wilkerson – University of Wisconsin-Madison

Kimber L. Wilkerson – University of Wisconsin-Madison

Kimber L. Wilkerson is a professor in the Department of Rehabilitation Psychology and Special Education at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Her work focuses on enhancing outcomes for students with disabilities. This includes investigating the efficacy of alternative education settings and examining accountability policies on the delivery of special education services.