The vast majority of Americans who commute to work do so by car, and many policymakers in America’s towns and cities are trying to change this by encouraging more healthy alternatives such as cycling. To look at how this might be achieved, Robert Boyer examined cycling habits in Charlotte, North Carolina. He finds that riding a bike for recreation can be a ‘gateway activity’, making it more likely that a bicycle will also be used for utility purposes such as commuting to work. In combination with infrastructure improvements – such as bike lanes – policymakers, can promote cycle commuting by inspiring more recreational cycling, thus allowing riders to safely improve their skills.

The vast majority of Americans who commute to work do so by car, and many policymakers in America’s towns and cities are trying to change this by encouraging more healthy alternatives such as cycling. To look at how this might be achieved, Robert Boyer examined cycling habits in Charlotte, North Carolina. He finds that riding a bike for recreation can be a ‘gateway activity’, making it more likely that a bicycle will also be used for utility purposes such as commuting to work. In combination with infrastructure improvements – such as bike lanes – policymakers, can promote cycle commuting by inspiring more recreational cycling, thus allowing riders to safely improve their skills.

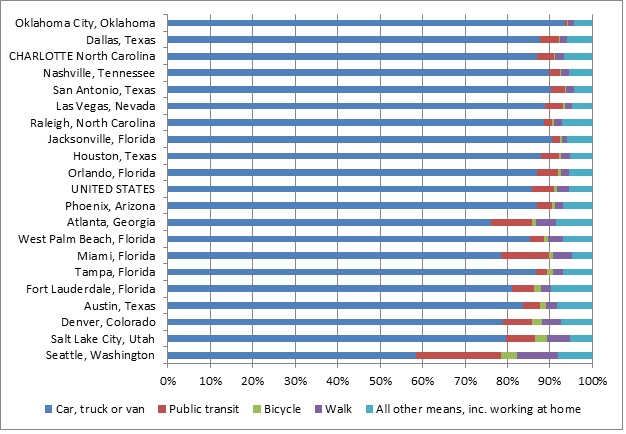

Riding a bicycle is a low-cost, low-carbon form of transportation, with health benefits for the cyclist and the larger community. In Charlotte, North Carolina—and cities all over the United States— less than one percent of commuters ride a bike to work on a normal workday. Meanwhile 87 percent of Charlotte commuters drive to work in a car, and most of them drive alone (see Figure 1). To counter this trend, Charlotte-area planners and elected officials have invested in expanding the city’s bicycle infrastructure, yet data on who cycles to work in Charlotte reveals that one key to substantially increasing the number of bicycle commuters may be creating opportunities for residents to ride their bikes recreationally, at times and in places where they can rehearse for a more challenging commute.

Figure 1 – Means of transportation to work for central cities of large, fast-growing metropolitan areas of the United States

Source: US Census Bureau, American Community Survey 2015 5-year estimates, Means of Transportation to Work.

*Includes the core cities of the twenty fastest-growing metropolitan statistical areas with populations greater than 1 million, between years 2010 and 2016. Cities are sorted by percent of bicycle commuters.

Charlotte’s addiction to cars

There are good historical reasons for Charlotte’s ‘addiction’ to the car: the City’s population has quintupled since 1950, during which time the car grew into the single dominant form of transportation in the USA. According to a recent analysis of sprawl in US urban regions, Charlotte has ascended the ranks to the fifth most “sprawled” city in the US: urban development is both low-density and poorly ‘mixed’, making travel by means other than the car time consuming, relatively expensive, and potentially dangerous.

In the past decade, Charlotte has invested in expanding its bicycle infrastructure network, growing from a single mile of bicycle lanes in 2001 to nearly 200 combined miles of on-street lanes, signed routes, and greenways as of 2017. In 2017, the city council budgeted an unprecedented $100 million for bicycle facilities over the next 25 years. Expanding this infrastructure network is critical for boosting bicycle commuting in Charlotte, but is it enough? Transitioning from an car-dominated city to a city in which cycling accounts for even a small percentage of commuters will likely require new that residents acquire new equipment, skills, and perceptions that investments in public infrastructure, cannot independently inspire.

Recreational cycling as a ‘gateway’ activity

Most existing research on why some individuals (and not others) ride a bicycle to work pays attention to either A) residential proximity to bicycle pathways (e.g. do individuals who live closer to bicycle lanes ride more often?) ; B) demographic characteristics like age, gender, race, education, and income (e.g. do young people ride more than old people?); or C) some combination thereof. Most of these studies focus on a single point in time, and show consistently that proximity to bicycle pathways is associated with more utility cycling and, in the United States, that younger, white men in high-density neighborhoods are more likely to ride their bikes to work than others. Longitudinal research, however, shows that the practice of bicycling comes and goes throughout life, and that certain life events like having children, making new friends that ride bicycles, or changing jobs can also help explain cycling behavior.

To date, little research has had the opportunity to examine the relationship between an individual’s recreational cycling habits and their utility cycling habits. Most data sources on bicycle commuting focus on the journey to work without probing individuals’ time spent riding for fun. Fortunately, the Charlotte Department of Transportation has included a question on individuals’ recreational cycling habits in their recent biannual transportation preferences survey.

A closer look at the data reveals that, first of all, twice as many Charlotte residents ride their bikes for recreation than for utility, and while only 46 percent of recreational riders are also utility riders, an overwhelming 85 percent of utility riders are also recreational riders. When controlling for demographic and geographic variables like age, gender, race, and proximity to bicycle lanes using a statistical model, the relationship between recreational and utility cycling is very strong: an individual who rides for recreation just once a month has about 7 times greater odds of riding their bike for utility purposes once a week than an individual who never rides; weekly and daily recreational riders show an even greater chance.

Why is this? A possible explanation is that recreational cycling serves as a sort of ‘gateway’ activity to utility riding. There are many temporal and spatial restrictions to commuting to and from work on a bike: you have to do it at a specific time, to a specific place, on a specific route. Your ability to ride a bike to work may be restricted by family obligations like picking up and dropping of children, by your work attire, or by the weather.

Riding for recreation, one confronts fewer restrictions. Inherently, recreational cycling can take place more often, in more places, with more people, in whatever comfortable attire you own. So it is possible that recreational cycling is serving as a sort of rehearsal platform for utility cycling. In a city where cycling is rare and perceived as dangerous, novices that ride even a little bit give themselves an opportunity to gain confidence on their bicycle, learn to navigate Charlotte’s winding roads, discover the attire and accessories that will allow them to ride in more places and more times, and perhaps make the bold choice of commuting to their place of work.

Figure 2 – Charlotte is home to dozens of ‘social rides’ that allow individuals to ride safely in large groups. The Plaza-Midwood Tuesday Night Ride (pictured above) is a weekly 15-mile ride for cyclists of intermediate skill level

Of course, some very long commutes may always prove impractical or intimidating, but there are thousands of Charlotte residents who live within a 20 minute bike ride of their jobs, and according to census estimates, hundreds of residents who already make the choice to commute by bicycle every day.

Another significant factor in the statistical model was ‘bicycle network density,’ or miles of bike lane per acre of land area in a respondent’s ZIP code (roughly, their neighborhood). All things equal, an individual in a neighborhood with one extra mile of bike lanes has 1.5 greater odds of riding once a week for utility purposes. This finding is consistent with prior research that shows a positive association between a high density of bikeway facilities and bicycle ridership.

So while this research does not necessarily contradict the conventional wisdom— that more bike lanes, greenways, and signed bicycle streets results in more cycling to work—policy makers in auto-dominated cities like Charlotte ought to consider that much of their population may lack the skills, equipment, or confidence to even contemplate riding a bicycle to and from work. Inspiring more riders may require an extra step, allowing individuals to build the skills slowly, safely, at flexible times and in more flexible spaces.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Recreational bicycling as a ‘gateway’ to utility bicycling: The case of Charlotte, NC’, in the International Journal of Sustainable Transportation.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2ChZhTh

_________________________________

About the author

Robert Boyer – University of North Carolina- Charlotte

Robert Boyer – University of North Carolina- Charlotte

Robert Boyer is an Assistant Professor of Urban Planning in the Department of Geography & Earth Sciences at the University of North Carolina- Charlotte. His research focuses the importance of community and interpersonal relationships in sustainable urbanism. He loves riding his bicycle.