In the lead-up to the 2016 Democratic primary, most commentators believed that former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton would easily win her party’s nomination while the Republican field would be consumed by infighting. While Donald Trump became the Republican nominee in early May of 2016, Clinton took a further month to secure her own party’s nod. In new research Josh M. Ryan finds that Clinton’s delay was not an outlier – since 1980, Democratic candidates who make it through the first three months of a nomination race are less likely to drop out than are Republicans. He writes that the GOP gives its candidates an electoral bonus for winning a state’s primary election, meaning that their field tends to clear earlier than the Democrats’.

In the lead-up to the 2016 Democratic primary, most commentators believed that former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton would easily win her party’s nomination while the Republican field would be consumed by infighting. While Donald Trump became the Republican nominee in early May of 2016, Clinton took a further month to secure her own party’s nod. In new research Josh M. Ryan finds that Clinton’s delay was not an outlier – since 1980, Democratic candidates who make it through the first three months of a nomination race are less likely to drop out than are Republicans. He writes that the GOP gives its candidates an electoral bonus for winning a state’s primary election, meaning that their field tends to clear earlier than the Democrats’.

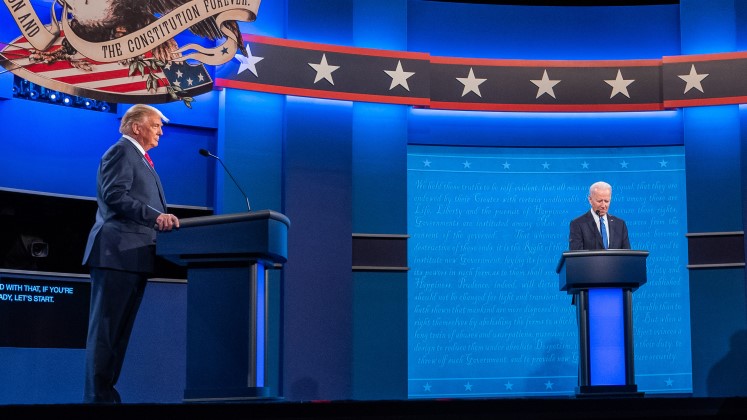

The 2016 Democratic presidential primary was surprisingly competitive and long-lasting. Hillary Clinton, despite creating a powerful campaign apparatus and being the odds-on favorite, had trouble shaking her opponent, Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont. In many ways, the 2016 primary mirrored what occurred to Clinton in 2008, when she lost the nomination after a drawn-out battle to future president Barack Obama.

Since the creation of the modern primary system, which most observers trace to about 1980, Democratic candidates seem to have a much tougher time pulling away from their rivals and securing the nomination as compared to Republicans. To what extent does this perception match reality, and why might Democrats systematically take longer to select their nominee? Using data from both parties’ primary elections since 1980, I find strong evidence that Democratic primary fights last substantially longer than those in the Republican Party. Why? Republican voters give their candidates an electoral bonus for winning a state, likely due to the party’s delegate allocation rules. Conversely, Democratic candidates receive no bonus from voters in subsequent state primaries for a win, allowing Democratic hopefuls to stay in the race longer and prevent the eventual winner from consolidating the vote. The implications of this process extend beyond the dynamics of the primary campaign; there is substantial evidence that more divisive primaries hurt candidates in the general election.

The presidential primary is unique among American elections in that it occurs across multiple states on multiple days, with voters going to the polls between January and June of a presidential election year, depending on the state. Candidates may enter or leave the race at different times, and voters in one state can learn about the performance of a candidate from previous elections in another state. This also means that candidates work hard to develop “momentum” by performing well in early states hoping to boost their prospects in later states. When a candidates does well in New Hampshire for example (traditionally the site of the first presidential primary), the candidate is taken more seriously by voters, donors, and the media, causing an increase in both campaign contributions and attention, which in turn gives the candidate additional support among voters in later states. In this way, winning votes in a state primary or caucus leads to additional support by voters in subsequent state elections, while candidates who do poorly in a state can quickly see their fortunes decline. Indeed, many believe that Barack Obama benefited from his strong and surprising showing in Iowa in 2008, which led the media and the Democratic Party establishment to re-evaluate his prospects while increasing support among the Democratic rank-and-file.

This feedback cycle, where support for candidates increases in subsequent states as their performance in state primaries improves, does not work the same way for both parties. My data show that all primary candidates receive more support in subsequent states when they perform better in a state election, but only Republicans see an additional, “bonus” increase in support when they win a state. For Democrats, winning a state is not as important as simply performing well overall. For example, in 2008 Hillary Clinton won approximately 39 percent of the vote in the New Hampshire primary while Barack Obama won 36.5 percent of the vote. The fact that Clinton received more votes helped her do well in subsequent elections, but if this had been the Republican primary, Clinton would have received an additional electoral bonus in future state primaries simply for winning the state, regardless of how close the actual vote total was.

“Bernie Sanders” by Gage Skidmore is licensed under CC BY SA 2.0

This extra bonus to Republican candidates for a win has some important effects. If a Democratic candidate can keep the vote margin close, support in future state primaries does not depend on whether they won previous primaries. The result is that Democratic candidates can receive roughly the same level of support from Democratic voters, even if they do not rack up state wins. This has the effect of encouraging Democratic candidates to stay in the race. Since 1980, Democrats have been more likely to drop out early in the race, but if they make it through the first three months of the primary campaign, they become much less likely to quit than Republicans. Any given Republican candidate is about 20 percent more likely to quit the race once the campaign is about two-thirds of the way through (about mid- to late May in most recent primary campaigns) as compared to Democrats. As a result, over the course of the primary, Democratic candidates do not consolidate the primary vote as fast as Republican candidates do, which drags out the process.

To measure how difficult it is for Democrats to consolidate the primary vote, I examined the average Election Day vote share received by the Republican and Democratic winners since 1980 across the primary calendar. (One important caveat: I only examined competitive primaries, with no incumbent president or vice-president running.) In 2016, despite the number of candidates in the Republican race, the lack of endorsements or fund-raising by Trump, and the outright opposition to him by much of the party elite, his average vote share steadily increased across time, reaching 50 percent on the 12th primary contest day (April 19th, which was New York’s primary) and never dipping below that subsequently. Clinton, on the other hand, won over 50 percent of the vote on February 23rd, then 73 percent of vote on February 27th, but three primary elections later received only 36 percent of the vote. Clinton received less than 50 percent of the vote as late as June 7th, and never managed to decisively pull away from Sanders. In fact, only Bill Clinton in 1992 was able to consolidate the Democratic vote over time in a way similar to every Republican candidate with the exception of Reagan in 1980.

Why do Democratic voters not reward candidates for winning states, and prevent the front-runner from consolidating the primary vote? It is not, as some have suggested, that Republican voters are inherently more deferential to front-runners, or because money has a greater impact in Republican primaries. Instead, the Republican primary system mostly allocates convention delegates on a winner-take-all-basis, while Democrats tend to allocate delegates in a proportional manner. While the Democratic Party system is fairer in that it more directly reflects votes cast, the Republican system creates clearer winners and losers, which influences how voters perceive candidates. I cannot say for sure whether the winner-take-all mechanism is behind these differing primary dynamics, but the evidence suggests that it may well be. This raises the question of whether Democrats should move to a winner-take-all system. The drawn-out primary may hurt the Democratic nominee, but it is not clear the party’s voters would support a more decisive way of allocating delegates. And, if they did not, lowered enthusiasm for the nominee could be just as harmful as a drawn-out primary.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Partisan Dynamics in Presidential Primaries and Campaign Divisiveness’, in American Politics Research.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2HiV6IA

_________________________________

About the author

Josh M. Ryan – Utah State University

Josh M. Ryan – Utah State University

Josh M. Ryan is Assistant Professor of Political Science at Utah State University in Logan, Utah. He holds a Ph.D. from the University of Colorado at Boulder. His research interests in American institutions include Congress, the president, state legislatures, executives, and electoral institutions, with a focus on how rules structure representation and elite behavior. He is the author of the forthcoming book, The Congressional End Game: Interchamber Bargaining and Compromise and his work has been published in The Journal of Politics, Legislative Studies Quarterly, Political Research Quarterly, and American Politics Research, among other outlets.