Like the president, state Governors frequently make use of executive orders in order to pursue their agendas. But do these unilateral actions undermine democracy? No, argue Alexandra G. Cockerham and Robert E. Crew, Jr, who find that legislatures can be willing to delegate policy-making authority to governors if they are of the same party or if the legislature is fragmented.

Like the president, state Governors frequently make use of executive orders in order to pursue their agendas. But do these unilateral actions undermine democracy? No, argue Alexandra G. Cockerham and Robert E. Crew, Jr, who find that legislatures can be willing to delegate policy-making authority to governors if they are of the same party or if the legislature is fragmented.

In the month following his January 16th inauguration, the new Governor of New Jersey, Phil Murphy, signed 11 major executive orders on issues ranging from equal pay to access to health insurance to marijuana policy. While in studies of the presidency such actions are usually seen as a way to circumvent a disagreeable Congress, many scholars who study US state governors now suggest that such unilateral action may not be driven exclusively by efforts to circumvent a hostile legislature. Instead, they may come also as a response to delegation granted by the legislature as a means of expediting action. If this is true, then concerns that unilateral action invariably shifts the institutional balance of power in favor of the executive and threatens democratic government may be overblown.

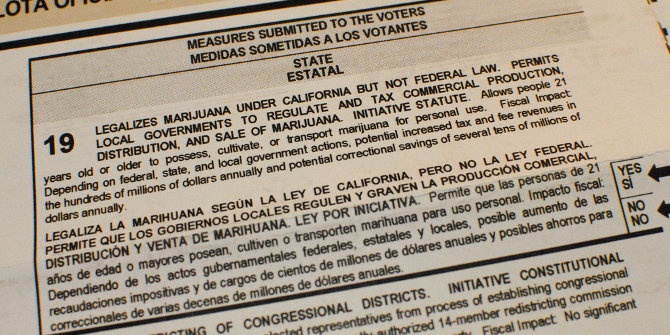

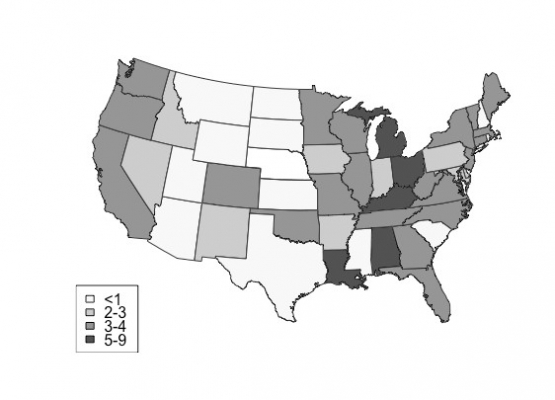

Existing research on unilateral action focuses on one governmental setting, the presidency, which limits our understanding of how chief executives with different degrees of formal power use unilateral action and about how legislatures of varying capacity respond. In new research, we examine the use of executive orders in a cross-sectional context (the US states), thus providing a more comprehensive perspective of where unilateral action fits in relation to other executive powers and why it is used. The executive orders we examined are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 – Distribution of Average Number of Significant Policy-Relevant Executive Orders (Among State-Years, 2010-2014)

Note: Alaska had an average of 0.75 executive orders per year and Hawaii had an average of 2. Also, Nebraska is not colored on the map because it is omitted from our analysis.

Bargaining Between the Governor and the State Legislature

The legislative process cements a policy into law. If a governor were guaranteed complete bargaining success and the legislature were assured that legislation would conform exactly to the majority party’s policy preferences, both branches would prefer to formulate policy via the legislative/bargaining process. Typically, however, bargaining with the legislature requires some compromise from the governor. Thus, governors can accept policies they view as less than ideal but that are more likely to endure, or they can implement their ideal policies, knowing that they could be overturned when they leave office. As a governor’s expected success from negotiating with the legislature declines, he or she has less incentive to bargain and greater incentive to circumvent the legislature by issuing executive orders.

Previous research on the use of executive orders, conducted almost exclusively on the relationship between the President and the US Congress, shows that the variation in the use of these orders is driven to a large extent by the political relationship between the two institutions. We suggest that the use of executive orders may also be related to the institutional strength of either of these two bodies.

Powers of the Legislature

Professional legislators work full-time at the job and have more staff members than part-time or citizen legislators. Thus, they have a greater capacity to gather information and formulate policy, giving them a bargaining advantage. In addition, comparative studies have shown that when the legislature and executive are of the same party but the legislature is unable to get its desired policy passed due to lack of capability (time, staff, etc.), legislators may accede to the use of executive orders. Under these conditions, the legislature may delegate authority to the governor, sitting by supportively while the governor uses an executive order to move policy in the direction of the unified party.

Powers of the Executive

Since a higher level of formal power gives the executive more influence when interacting with both the legislature and the bureaucracy, a stronger governor would likely prefer to bargain with the legislature so that the resulting policy will be more durable and to avoid rancor that might affect future interactions.

“New Jersey Governor Phil Murphy signs his first Executive Order promoting equal pay for women on Tuesday, January 16th, 2018. Edwin J. Torres/ GovernorÕs Office.” by Phil Murphy is licensed under CC BY NC 2.0

What we found

We used regression models to test hypotheses around the relationship between the number of executive orders issued by a governor and their level of formal power, whether the government is divided and how professional or fragmented the legislature is.

We find that a governor will act unilaterally when bargaining with the legislature is costly – that is, if a governor is relatively weak or when legislative capacity is strong, he or she will issue more executive orders. In addition, our results show that the legislature will relinquish policy-making authority to the governor when it is of the same party as the governor and when it has less operational capacity (e.g. is less professional or more fragmented).

Why we shouldn’t be nervous about governors’ use of executive orders

Our analysis illustrates the importance of considering the use of executive orders across the US states. American-based theories of unilateral action predict that executives will use these instruments to usurp legislative power and that their extensive or easy use could lead to a break down in the balance of power between the executive and the legislature.

Our results show that governors use executive orders both in response to legislative delegation and as a way to circumvent legislative authority. We have also shown that legislatures are willing to delegate policy-making authority to the executive rather than be stymied by fragmentation or low professionalism.

The results from our analysis lead us to suggest that concerns about excessive use of unilateral action may be unnecessary. First, stronger chief executives appear to use their formal powers to bargain with legislatures rather than to threaten them with unilateral action. In addition, there are instances in which legislatures may favor the use of unilateral action.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Factors Affecting Governors’ Decisions to Issue Executive Orders’, in State and Local Government Review.

Please read our comments policy before commenting

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2HupX9L

About the authors

Alexandra G. Cockerham – Florida State University

Alexandra G. Cockerham – Florida State University

Alexandra G. Cockerham is a Visiting Assistant Professor at Florida State University. Her research interests center on executive power, with an eye toward the limitations that institutions impose on directly elected executives. Her dissertation is one of the first research designs to examine the use of executive unilateral action in a cross sectional context, such that competing hypotheses might be subjected to systematic testing. Together with Dr. Crew she has several publications including an article in State and Local Government Review and a book chapter on campaigning at the local level.

Robert E. Crew, Jr – Florida State University

Robert E. Crew, Jr – Florida State University

Robert E. Crew, Jr. is Professor of Political Science and Director of the graduate Program in Applied American Politics at Florida State University. His research focuses on American social policy and American state and national politics and public management. He has several publications examining executive politics in the Social Science Journal, The Journal of State Government, State Politics and Policy Quarterly, and Political Psychology.