Last week, ABC cancelled the newly returned sitcom, Roseanne, in the wake of the racist and extremist statements made on Twitter by its titular star. Ben Margulies writes on how Roseanne – the actress – has been made into a populist avatar taken by the media and many on the left to be representative of all of Donald Trump’s supporters. While before the star’s outburst, Roseanne was seen to represent a white working class driven by economic desperation to vote for Trump. Now, he argues, that same group are seen as irredeemable racists who can be easily condemned by the left.

Last week, ABC cancelled the newly returned sitcom, Roseanne, in the wake of the racist and extremist statements made on Twitter by its titular star. Ben Margulies writes on how Roseanne – the actress – has been made into a populist avatar taken by the media and many on the left to be representative of all of Donald Trump’s supporters. While before the star’s outburst, Roseanne was seen to represent a white working class driven by economic desperation to vote for Trump. Now, he argues, that same group are seen as irredeemable racists who can be easily condemned by the left.

We children of the ‘90s remember that comedian Roseanne Barr was always a scandalmonger. In 1990, she gave a famously grating rendition of the national anthem at a San Diego baseball game, drawing a rebuke from the first President Bush. American popular culture has never been short of celebrities who, for whatever reason, become too colourful for commercial broadcasting.

But in the 1990s, Roseanne Barr was notable because she was a celebrity, and not because her antics had deep political resonance. Though her sitcom, Roseanne, which initially ran on the ABC network between 1989 and 1997, always evoked the struggles and issues of the working class, Barr wasn’t seen as an icon of the era’s culture wars. At that time, the country’s most fevered fault lines tended to deal with social conservatism vs. social liberalism, rather than class; immigration and race were issues, but national-level politicians were less likely to centre their appeals on overt anti-immigrant or racist claims (though race was often the subtext to discussions of crime and welfare, as it is now). Sitcoms mainly figured in politics when they touched on social issues: President Bush famously condemned The Simpsons, while his vice president, Dan Quayle, called out fictional journalist Murphy Brown, played by Candice Bergen, for setting a poor example when she became a single mother. (Murphy Brown is also being revived.)

How Roseanne and Roseanne embody the white working class

During the 2016 presidential election, Donald Trump refocused the country’s cultural divide, shifting emphasis to a large degree from cultural issues associated with religiosity to divisions based on globalization, race and borders. Trump played on pre-existing and latent conflicts to forge a platform based around hostility to non-whites, globalization, immigration and elites, one which encompassed – indeed, took as its core – the white working class that Roseanne Barr had embodied.

So when ABC revived Roseanne in 2018, both the character and the actor were Trump supporters, with all that entailed. ABC did this despite knowing that Barr had a long history of controversial, racist and extremist statements. On the show, the fictional Roseanne Connor cited Trump’s economic agenda as the motivation for her support. On Twitter, Roseanne Barr was a conduit for the racist, populist and conspiratorial strains in Trumpian discourse. On May 29, she tweeted that Valerie Jarrett, an African-American former counsellor to President Barack Obama, was the offspring of the “Muslim Brotherhood and Planet of the Apes.” ABC immediately cancelled her show.

Barr was initially profusely apologetic. However, we should not expect this to last. Radical right-wing populists don’t say sorry – or if they do, they don’t stay sorry. Ruth Wodak, in her The Politics of Fear, explained the process that unfolds when a radical-right populist politician makes a controversial or racially charged statement. First, the right-wing politician will deny having said anything offensive, or claim to have been misquoted. Then, they will charge that they are being persecuted by the politically correct media, engaging in what Wodak calls victim-perpetrator reversal. This fits the mindset of the populist constituency, the image of the “real people” oppressed and afflicted by wicked and collusive elites. The resulting controversy draws attention to the right-wing politician and mobilises the party base.

Barr may or may not run for public office again – believe it or not, she mounted a presidential run in 2012. However, Barr may try to use her “oppression” to win over support from Trump’s base of supporters to find an outlet somewhere in the right-wing media. Populist politics and the media share a common environment, and a common desire to curate an atmosphere of conflicts, as Benjamin Moffitt astutely observed. Trump, Moffitt notes, through his performance embodies the values and identity of the (primarily) white voters he represents, and their idea of America. Many other controversial right-wing political figures have used both an anti-elitist narrative and notoriety to carve out niches in American media, such as former vice-presidential candidate Sarah Palin, former Arkansas governor and presidential candidate Mike Huckabee, and Iran-Contra figure Oliver North.

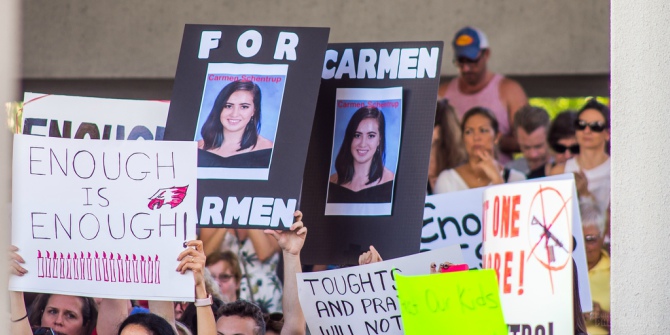

“A Day In New York 04.03.2018” by The All-Nite Images is licensed under CC BY SA 2.0

Two views about Trump’s supporters

I want to go back to the idea of Roseanne Barr as a populist avatar on her own account. In populism, the leader stands for the people and also the nation, which is possible because the people and nation are all of one mind and background, conceived as one organic body. So Barr is immediately taken as representative of Trump’s America, which explains why many (if far from all) conservative voices in the media rushed to excuse her or deny the racist content of her tweets. Populists imagine not just a homogenous people, but one under siege; the highest moral duty is to defend one’s own, rather than the anti-racist norms supposedly universal in American society (but really a tool of the “elites”).

Another consequence of populism, though, is that the populists’ opponents begin to adopt some of populism’s own characteristics. Takis Pappas describes how Greek parties tended to adopt populist framings and rhetoric in sequence – the socialists first, then the conservatives – each remaking the other subject in its own image. So Trump’s opponents tend to see his voters in a reductive manner.

One reason that ABC decided to revive Roseanne was to reach out to the Trump people-nation. That tells you something about how the directors of American media see Trump’s camp; as essentially the fictional Connors writ large, evoking a common media narrative. However, this is not an accurate depiction of Trump voters, who were, to a large extent, the existing cross-class Republican coalition, and often lower-middle class.

The Roseanne saga thus demonstrates two contradictory views that many liberals/Democrats/coastal elites, and the media outlets associated with these groups, have about the white-working class. The first is that they are all desperately poor but generally moral people driven to vote for Trump by economic desperation. This is the myth of “white innocence” that Ta-Nehisi Coates describes. This allows upper-class liberal whites to absolve their poorer brethren and continue to appeal to them as voters and customers, and to preserve the value of “whiteness” for everyone.

But once Barr’s Twitter feed caught fire, the other view of the white-working class emerged – as irredeemable racists. Coates’s piece implies why this is also useful for white elites. By condemning white working-class racism, middle-class whites can ignore how whites of all classes exploit and benefit from racism. They can also excuse themselves achieving a more just society because racist white-working class voters blocked their well-meaning efforts. Alternatively, they can abandon any plans for redistributive policies, because working-class white voters do not deserve them.

The Roseanne affair is a telling episode in the politics of the Trump era. Americans in both camps have constructed an idea of the “white working class” as a sort of touchstone of identity, a symbol of something essential about America that must be embraced or rejected. However, the “white working class” that the right courts and the left fears is a narrative, a story, no different from the one Roseanne’s writers were telling. And neither Trump nor Barr have a monopoly on storytelling.

Please read our comments policy before commenting

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2JjlPdi

About the author

Ben Margulies – University of Warwick

Ben Margulies – University of Warwick

Ben Margulies is a Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Warwick.