Over the past two decades, Latinos in America have gone from being told that they did not belong in 2006, that they held the electoral balance of power in 2012, and finally back to rejection again with the election of President Trump in 2016. In new research, Melissa R. Michelson and Jessica L. Lavariega Monforti examine the effects of these changing societal messages and sometimes outright racism on Latinos’ cynicism about, and participation in, politics. They find that, compared to 2012, Latinos are now more likely to be interested and participate in politics, at the same time as having far less trust in government.

Over the past two decades, Latinos in America have gone from being told that they did not belong in 2006, that they held the electoral balance of power in 2012, and finally back to rejection again with the election of President Trump in 2016. In new research, Melissa R. Michelson and Jessica L. Lavariega Monforti examine the effects of these changing societal messages and sometimes outright racism on Latinos’ cynicism about, and participation in, politics. They find that, compared to 2012, Latinos are now more likely to be interested and participate in politics, at the same time as having far less trust in government.

While barred from voting in US elections, undocumented immigrants can potentially participate in the political arena in many ways, such as attending meetings or joining protest marches and demonstrations. Previous research has found mixed evidence of the degree to which such participation occurs in the undocumented Latino community, and that it varies with political context, age at immigration, and undocumented collective identity. Using a series of public opinion polls, we compare reported levels of political trust and rates of non-electoral political participation from 2012, after the reelection of Barack Obama, and from 2016-2017, after the election of Donald Trump. Overall, we find significant evidence that Latinos overall, including undocumented Latinos, were more cynical and more politically active in 2016 than in 2012.

The degree to which all residents of the United States, including citizens, permanent residents, and undocumented immigrants, are politically engaged is a reflection of the health of our democracy. As Irene Bloemraad notes in her book, Becoming a Citizen: “When residents of a country do not acquire citizenship or fail to participate in the political system, not only is the sense of shared enterprise undermined, but so too, are the institutions of democratic government.” Examining rates of participation among non-citizens, in particular, allows for consideration of the degree to which these new members of our society are being politically socialized into active membership.

“March for Immigrants Chicago Illinois 6-30-18 2240” by Charles Edward Miller is licensed under CC BY SA 2.0

Over the past decade Latinos have experienced polar extremes in terms of societal messages about their degrees of belonging and political power. In 2006, Latinos were told that they did not belong. In 2012, they were told that they had the power to determine the outcome of the presidential election”. In response to this shifting context, Latinos were consistently politically active (e.g. the 2006 immigration marches), but their political attitudes shifted from cynical to more trusting, particularly among US citizens. Non-citizens and especially undocumented Latinos, in contrast, remained outsiders with high levels of cynicism.

In 2016, the political context shifted once again, particularly after Trump’s electoral victory. Trump entered the political arena in mid-June 2015 with an attack on Mexican immigrants, calling them criminals and rapists, and promised to build “a great wall” to keep them out. Chants of “Build the Wall” became a staple of Trump’s campaign rallies and post-election town halls. Trump continued to make racist comments through Election Day, and his anti-Latino and anti-immigrant rhetoric and actions did not stop after he was sworn in as president.

Did Trump’s racism make Latinos more cynical about politics?

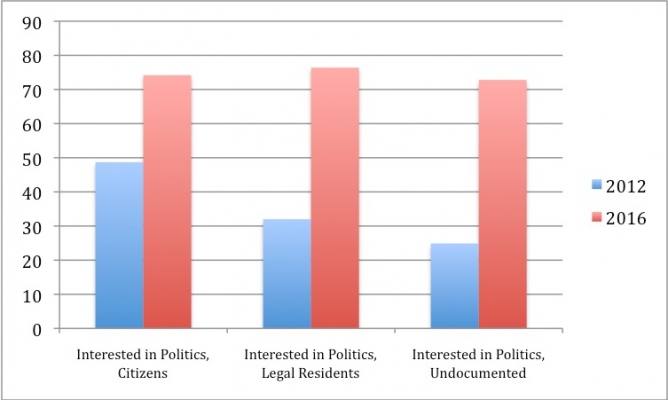

We hypothesized that this racism made Latinos more cynical (as a rational response to current events) and also more active (including increased political interest and reported participation), in order to empower their communities. We expected to see these shifts among all Latinos, regardless of immigration status, including citizens, legal residents (documented non-citizens), and undocumented immigrants. To examine Latinos’ interest in politics we used the 2012 Latino Immigrant National Election Study and the 2016 Collaborative Multiracial Post-Election Survey. As shown in Figure 1, interest in politics was much higher in 2016 than in 2012, across all types of Latino respondents.

Figure 1 – Latino interest in politics in 2012 and 2016

Note: Interest in politics in 2012 includes responses of “always” and “most of the time.” Interest in 2016 includes “very” or “somewhat” interested in politics.

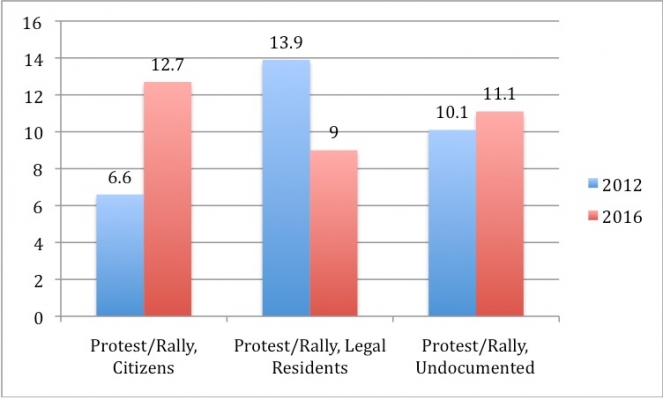

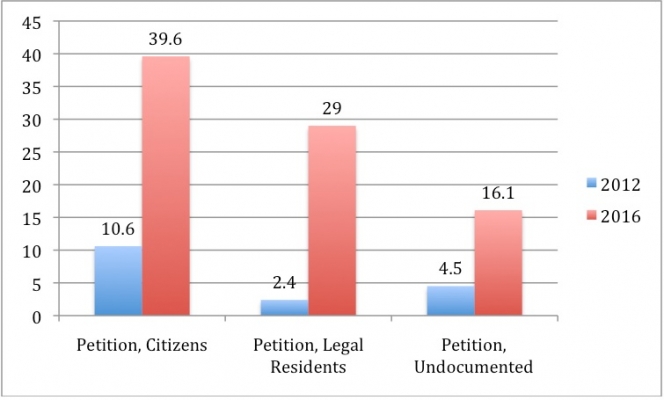

Moving beyond reported interest to actual political behavior, both surveys asked respondents a similar set of questions about political activity across several types of political engagement, including attending protests, wearing a button or displaying a sign, and signing a petition. Overall, there is a clear pattern of increased participation on all items, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2 – Latino Political Participation, 2012-2016

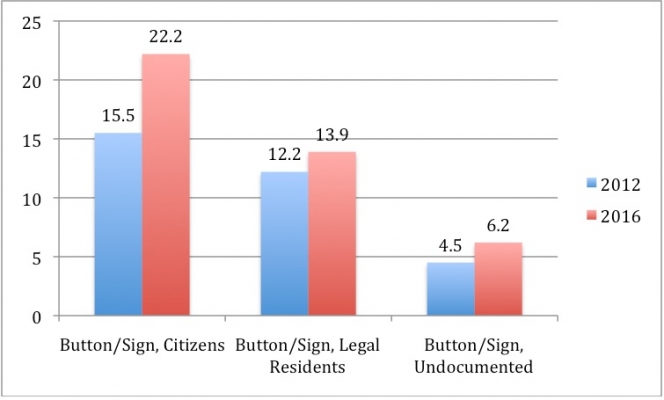

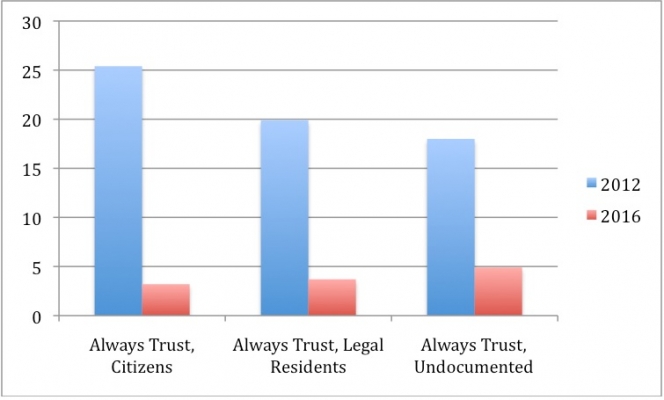

We also examined feelings of trust in government among LINES and CMPS respondents. As shown in Figure 3, in 2012, trust was strong across all three subgroups of Latinos: between one in four and one in five respondents said they trusted the government “just about always.” In contrast, just four years later the CMPS registered much lower levels of trust in government, with fewer than one in 20 Latinos in any subgroups of respondents giving the “just about always” response. This is a significant drop in level of trust.

Figure 3 – Latino trust in politics in 2012 and 2016

Latinos in the Era of Trump

In 2012, Latinos were cautiously optimistic that a second term for Obama might bring immigration reform. The mass media proclaimed 2012 the year that Latinos would decide the presidential election, and the phrase “demography is destiny” suggested an even stronger political voice for the community as their numbers continued to increase. Just four years later, however, the national mood had shifted dramatically. Trump’s campaign and early presidency were notably anti-immigrant and anti-Latino, including increased internal enforcement of immigration law leading to front-page stories of deportations, and congressional approval for the first sections of border wall, in Texas and California.

Latinos responded to this shift in national context. Citizens, legal residents, and undocumented immigrants all reported increased levels of political interest, increased levels of non-electoral political behavior, and increased cynicism. This is not a coincidence: Latinos were listening—in both 2012 and 2016—and their responses are logical reactions to the rhetoric and actions of Obama and Trump.

These data are an important reflection of how our political rhetoric and policies reflect our values as a country, and our ability to live up to our reputation as a land of opportunity and a nation of immigrants. That Latinos across the spectrum of immigration status, including citizens, are now so cynical about their government is a troubling reflection of our ability to live up to our ideals.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Back in the Shadows, Back in the Streets’, in PS: Political Science & Politics.

Please read our comments policy before commenting

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2mHYAvT

About the authors

Melissa R. Michelson – Menlo College

Melissa R. Michelson – Menlo College

Melissa R. Michelson earned her PhD in political science from Yale University and is currently Professor of Political Science at Menlo College. She is the award-winning author of four academic books: Mobilizing Inclusion: Redefining Citizenship through Get-Out-the-Vote Campaigns (Yale University Press, 2012), Living the Dream: New Immigration Policies and the Lives of Undocumented Latino Youth (Paradigm Publishers, 2014), A Matter of Discretion: The Politics of Catholic Priests in the United States and Ireland (Rowman & Littlefield, 2017), and Listen, We Need to Talk: How to Change Attitudes about LGBT Rights (Oxford University Press, Feb. 2017). She has published dozens of articles in top-rated peer-reviewed academic journals, including pieces in American Political Science Review, Journal of Politics, and International Migration Review. Her current research projects explore voter registration and mobilization in minority communities and persuasive communication on LGBT rights. In her spare time, she knits and runs marathons.

Jessica L. Lavariega Monforti – California Lutheran University

Jessica L. Lavariega Monforti – California Lutheran University

Jessica L. Lavariega Monforti’s research primarily focuses on the differential impact of public policy according to race, gender, and ethnicity. She is specifically interested in the political incorporation and representation of Latinos, immigrants, and women. Her latest research examines how major forces such as technology, the military system, and immigration policy impact and are impacted by Latino youth. She has worked with organizations such as Texas Rio Grande Legal Aide, La Union del Pueblo Entero, and the South Texas Adult Resource and Training Center.