It is well known that Black Americans are targeted more often by police in traffic stops. But what happens after they are stopped? In new research, Joshua Chanin, Megan Welsh, and Dana Nurge reviewed nearly 260,000 traffic stop records from the San Diego Police Department, finding that Blacks were more likely than Whites to be subject to field interrogation interviews, but were no more likely to be arrested, and were less likely to receive a citation. This suggests that police traffic stops can be a form of racially biased ‘catch and release’, which are likely to do little to improve trust between Black communities and the police.

It is well known that Black Americans are targeted more often by police in traffic stops. But what happens after they are stopped? In new research, Joshua Chanin, Megan Welsh, and Dana Nurge reviewed nearly 260,000 traffic stop records from the San Diego Police Department, finding that Blacks were more likely than Whites to be subject to field interrogation interviews, but were no more likely to be arrested, and were less likely to receive a citation. This suggests that police traffic stops can be a form of racially biased ‘catch and release’, which are likely to do little to improve trust between Black communities and the police.

There is a large body of research which show that Black and Hispanic drivers are subject to increased scrutiny during traffic stops compared to White drivers. These findings extend to police officers’ decision-making around when to initiate a search, issue a ticket or citation, and execute an arrest, among others. Despite the abundance of scholarship on this issue, much remains unknown about how and why such disparities occur. One avenue in need of further investigation is the connection between discrete decision points during police-citizen interactions. For traffic stops in particular, we need deeper insights into how the sequence of post-stop interactions might be shaped by drivers’ race/ethnicity.

In an effort to understand the role of officer decision-making in the context of traffic stops, we used a statistical technique to review nearly 260,000 traffic stop records generated by San Diego Police Department (SDPD) officers between January 2014 and December 2015. This approach allowed us isolate the effect of race on officers’ decision-making by comparing the likelihood that two drivers who are largely similar by gender, age, stop reason, stop location, and other relevant characteristics, but differ by race, will be searched, ticketed, or found with contraband.

“New York State Police Traffic Stop” by dwightsghost is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Black drivers are more likely to be searched

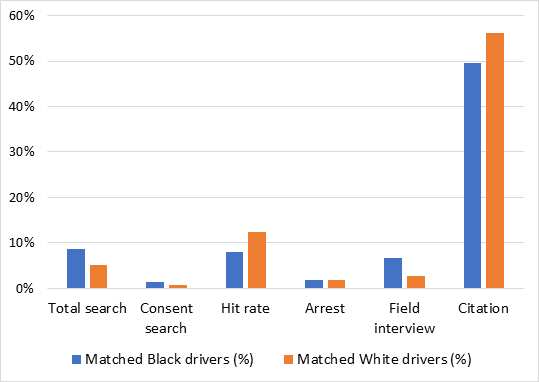

After isolating driver race, we found that Black drivers were more likely to be searched than similar (“matched”) Whites, a finding that was consistent across all search types, including highly discretionary consent searches, in which an officer requests and receives consent to search a driver’s vehicle and/or person. As Figure 1 shows, despite occurring at much greater rates, police searches of Black drivers were less likely to reveal possession of contraband – typically, weapons or drugs – than were searches of matched Whites. Black drivers were also subject to field interrogation interviews at more than twice the rate of matched Whites. Yet, despite the more aggressive protocols in place for Black drivers, our data shows no statistical difference in the arrest rates of matched Black and White drivers. Interestingly, Black drivers were also less likely to receive a citation than were matched Whites.

Figure 1 – Comparing post-stop outcomes for matched Black and White drivers

* denotes statistical significance at the 0.001 level

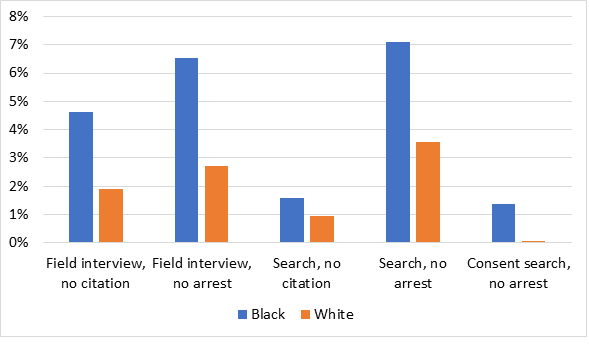

A more granular analysis of the post-stop data shows further race-based disparity. As shown in Figure 2 below, Black drivers were more than two times as likely as matched Whites to be subjected to field interviews where no citation was issued or arrest made. Blacks were also more likely to face a search that ended without either a citation given or arrest made. These data reveal what appears to be a practice that functions like a ‘catch and release’ program in which certain members of the community are stopped pretextually, investigated disproportionately for potential criminality, and then, should no evidence of wrongdoing appear, allowed to go free without any formal sanction.

Figure 2 – Sequential analysis of post-stop outcomes among matched Black and White drivers

Note: All racial differences are statistically significant at the 0.001 level

Trust and legitimacy are key

An enforcement approach that leads to these types of disparities carries tangible costs in terms of trust and legitimacy – both necessary components of well-functioning, modern law enforcement. That the San Diego Police Department continues to struggle to strengthen ties to the City’s most diverse communities, despite years of external scrutiny, increased officer training, and record crime lows, only underscores the point.

Research has shown that there is a strong race–crime association not just among police officers, but across the general population as a whole: Black faces are more frequently associated with criminal behavior than are non-Black faces. Some argue that this race-crime association manifests in “racial odds making,” where officers, whether acting individually or pursuant to department policy, increasingly scrutinize certain drivers based on “generalized perceptions of group criminality.” Others believe that racial disparities are a function not of overt racism, but of implicit bias. As Jennifer Eberhardt of Stanford University notes, “many subtle and unexamined cultural norms, beliefs, and practices sustain disparate treatment.”

More research – including qualitative research aimed at capturing officer perceptions of race and crime, how officer use of discretion shapes post-stop enforcement, and the influence of organizational and social group norms – is needed to better understand how these kinds of disparities persist. Until then, we urge police departments, including the SDPD, to consider whether the benefits of this inefficient and alienating traffic enforcement regime justify the strain such practices place on police-community relations.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Traffic Enforcement Through the Lens of Race: A Sequential Analysis of Post-Stop Outcomes in San Diego, California’, in Criminal Justice Policy Review.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2pY1z55

About the authors

Joshua Chanin – San Diego State University

Joshua Chanin – San Diego State University

Joshua Chanin is an Associate Professor in the School of Public Affairs at San Diego State University. Dr. Chanin’s research interests lie at the intersection of law, criminal justice, and governance. Recent work has been published in Public Administration Review, Police Quarterly, and Criminal Justice Review.

Megan Welsh – San Diego State University

Megan Welsh – San Diego State University

Megan Welsh is an Assistant Professor in the School of Public Affairs at San Diego State University. Dr. Welsh’s research interests include prisoner reentry, policing, and homelessness, and her work has been published in Feminist Criminology, the Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare, and the Journal of Qualitative Criminology & Criminal Justice.

Dana Nurge – San Diego State University

Dana Nurge – San Diego State University

Dana Nurge is an Associate Professor of Criminal Justice in the School of Public Affairs at San Diego State University. Dr. Nurge’s research focuses on gangs, youth violence, and juvenile prevention and intervention programming. She is currently serving as a Technical Advisor to the San Diego Commission on Gang Prevention and Intervention, and continues to conduct research on gangs.