In the aftermath of the 2018 midterm elections, President Trump blamed the election losses of many Republican incumbents on their refusal to embrace his policies. Sarina Rhinehart, Grayson Kuehl, Amy Vanderveer and Braden Zimmerman have closely examined the performance of those Republicans who did and did not support President Trump in the midterms. They find that Republicans in districts which were won by Trump by a small margin or voted for Hillary Clinton in 2016 tended to lose their seats, rather than where incumbents had not embraced the President.

In the aftermath of the 2018 midterm elections, President Trump blamed the election losses of many Republican incumbents on their refusal to embrace his policies. Sarina Rhinehart, Grayson Kuehl, Amy Vanderveer and Braden Zimmerman have closely examined the performance of those Republicans who did and did not support President Trump in the midterms. They find that Republicans in districts which were won by Trump by a small margin or voted for Hillary Clinton in 2016 tended to lose their seats, rather than where incumbents had not embraced the President.

In the lead up to the 2018 midterms, the media predicted that the public’s general displeasure with President Trump would lead to a ‘blue wave’ that would bring about major gains for the Democratic Party in the US Congress. Yet, in the aftermath of the election that flipped control of the House of Representatives, President Trump spoke out to reporters and on Twitter, blaming GOP losses on Republicans’ refusal to embrace his policies and principles in their campaigns. During a press conference the day after the election, Trump called out numerous Republicans who had failed to embrace him, including Rep. Mia Love (R-UT) who narrowly lost her bid for reelection. “Mia Love gave me no love,” Trump said. “And she lost. Too bad. Sorry about that Mia.”

https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump/status/1060141780878979072

One of the questions following the outcome of the midterms and Trump’s comments was what impact GOP incumbents’ embrace of Trump had on election outcomes, and if, as Trump speculated, those that failed to align their campaign with him were actually punished at the polls.

In 2016 we tracked how closely House Republicans aligned themselves with Trump during the 2016 campaign. House Republicans were coded on a 4-point scale based on how they spoke publicly about Trump from “no voiced support” to “enthusiastic support.” These data excluded uncontested races as well as races in which there was no social media or media coverage to determine Republican level of support for Trump.

Overall, we found that the underlying political partisanship of congressional districts best predicted incumbents’ support for Trump, such that those in Republican strongholds were the most likely to enthusiastically support Trump while those in moderate districts were more often to either remain silent or speak out against Trump.

“trump sign – 2016-11-08” by Tim Evanson is licensed under CC BY SA 2.0

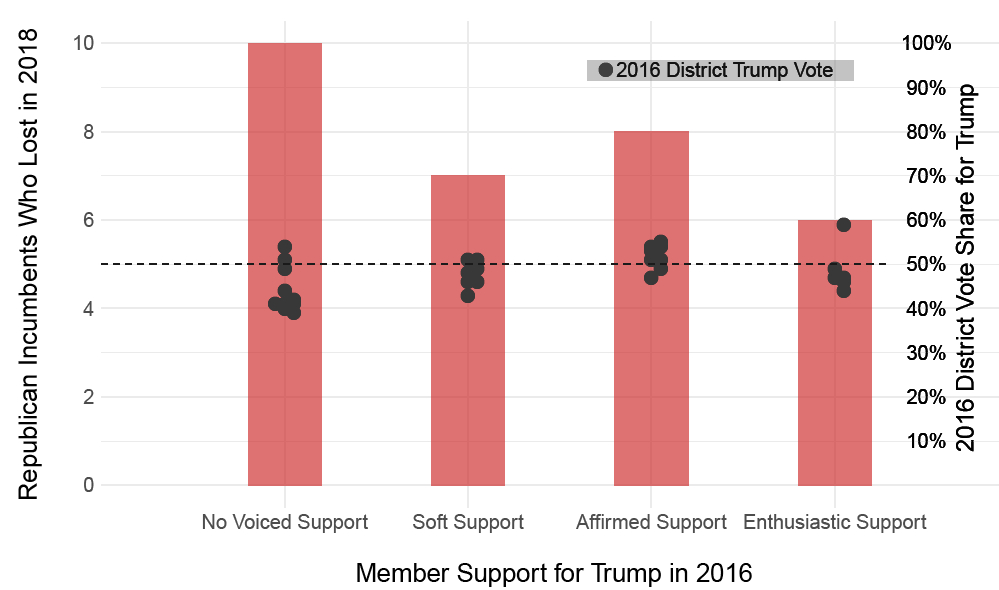

To gauge the effect of Trump on the 2018 election outcomes, Figure 1 examines the 31 Republicans in our dataset who lost in the 2018 midterms, including two who lost their primaries. We see that across the board these GOP losses were in weak Republican districts that either voted for Trump in 2016 by a small margin or were won by Clinton in 2016. Additionally, we do not see a strong distinction between the categories of support when considering why a candidate lost reelection. The determining factor seems to be more related to whether their district was “safe” for Republicans. If embracing Trump had been a large factor here, we would expect to see those who did not voice their support for the president to lose reelection at rates much higher than those who voiced enthusiastic support. However, this was not the case as Trump had speculated.

Figure 1 – Republican Incumbents who lost in 2018 and their support for Trump in 2016

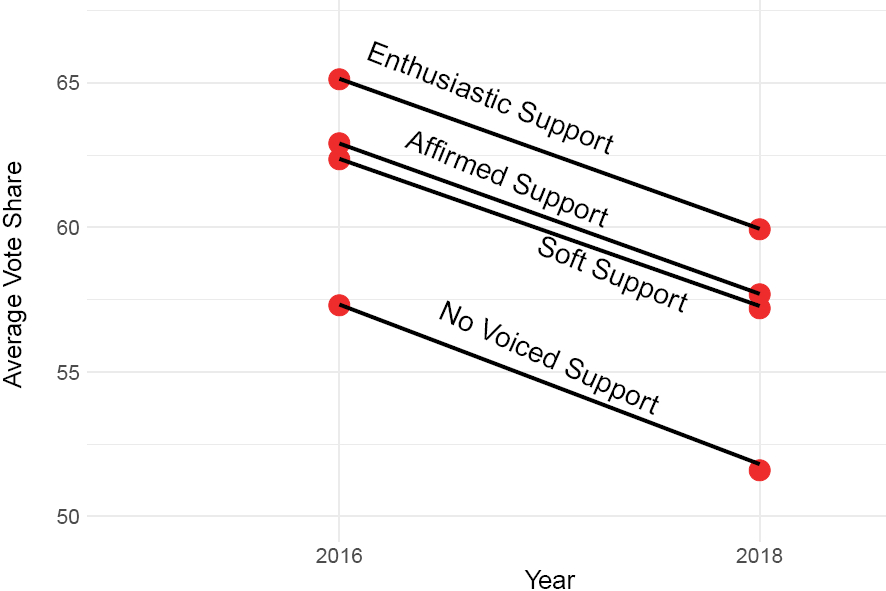

Figure 2 plots the average vote share of Republicans across the four categories of expressed support for Trump in 2016 and 2018. Whether the support for Trump was enthusiastic, affirmed, soft, or nonexistent, Republican incumbents saw on average a dip in their vote share from 2016 to 2018 of about 5 percent. Had level of support for Trump been a significant factor, we would expect to see major variances between the decreased vote share for Republican incumbents that voiced strong support for Trump and those that did not give any signs of support. These two figures suggest that the 2018 midterms were in line with typical midterm trends, such that the party in power loses seats.

Figure 2 – Republican average vote share in 2016 and 2018 by level of support for Trump

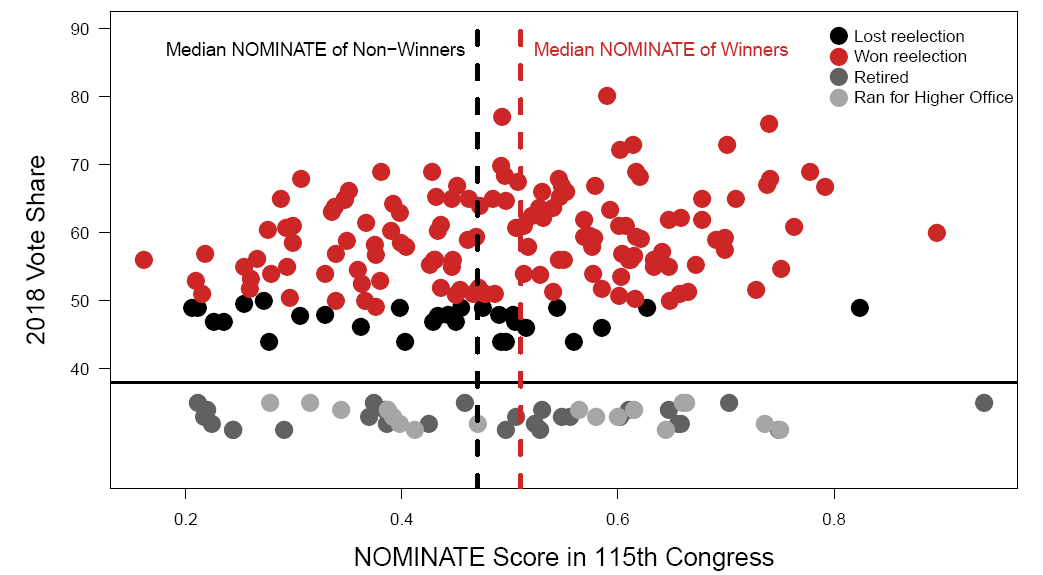

In addition to Republican losses, a substantial number of Republicans also retired in 2018. With that in mind, it is worth looking at who is returning to Congress in 2019 and who is not. Figure 3 shows the spread of Republican NOMINATE scores, a measure that runs from -1, the most liberal member of Congress, to 1, the most conservative. Looking at the median score of the losing candidates, they appear to be from the less conservative wing of the party, and in the New Year they will be replaced by Democrats, who will likely have more liberal voting records. This is most likely because moderate candidates run in swing districts, and those districts flipped in this election. This is not true of all moderate candidates, however, seeing many moderate candidates won and won by wide margins in some cases. Looking at the distribution of Republicans who left office voluntarily, they appear more diverse in ideology than the losers.

Figure 3 – Republican incumbent 2018 vote share and NOMINATE scores

Though much of the rhetoric surrounding the election centered on the “Trump effect,” the numbers do not support the claim that differing levels of support for Trump played a dramatic role in determining the outcome of the midterms. Rather, the Trump effect seemed consistent across our categories of support for Trump. What we see is not divergent from typical electoral patterns in a midterm election. Commonly, the president’s party will lose seats in districts that did not support him two years prior. Though the 2018 midterms marked a few exceptions of this pattern, notably the election of Kendra Horn in Oklahoma’s Fifth Congressional District, the results as a whole should not seem unexpected. While President Trump may claim those who did not support him must “say goodbye,” the results of the 2018 midterms indicate that his influence was far from achieving such an impact. The results of the midterms seem to show that expressing strong support for Trump could not save GOP seats from defeat.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Jumping on the Trump Train or Ditching the Donald: Campaign Rhetoric and the 2016 Congressional Election’ in the Journal of Political Marketing.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/2ByUrRQ

About the authors

Sarina Rhinehart – University of Oklahoma

Sarina Rhinehart – University of Oklahoma

Sarina Rhinehart is a graduate fellow at the Carl Albert Congressional Research and Studies Center at the University of Oklahoma.

Grayson Kuehl – University of Oklahoma

Grayson Kuehl – University of Oklahoma

Grayson Kuehl Is an undergraduate research fellow at the Carl Albert Congressional Research and Studies Center at the University of Oklahoma.

Amy Vanderveer – University of Oklahoma

Amy Vanderveer – University of Oklahoma

Amy Vanderveer is an undergraduate research fellow at the Carl Albert Congressional Research and Studies Center at the University of Oklahoma.

Braden Zimmerman – University of Oklahoma

Braden Zimmerman – University of Oklahoma

Braden Zimmerman is an undergraduate research fellow at the Carl Albert Congressional Research and Studies Center at the University of Oklahoma.