This section of the website is dedicated to the core United Nations human rights treaties that provide the foundation for international human rights law and their related monitoring bodies (i.e. “treaty bodies”). The goal is to provide you with information on each body, both in general and in relation to tackling violence against women.

Click on the sections below for a quick review on the UN Treaty Bodies and what you’ll find on each page. Then use the links on the right to learn about the specific human rights treaty that interests you.

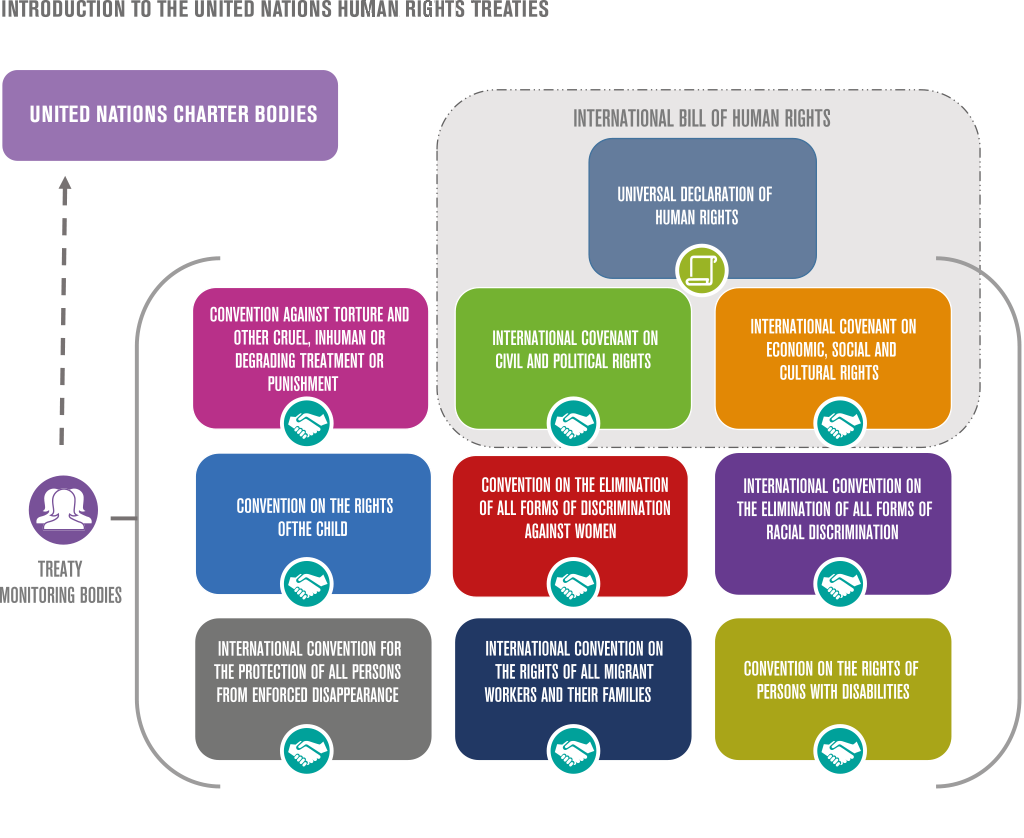

A diagram

At the top of each page you will introduced to the system through a diagram representing the relevant Treatyi, Optional Protocol(s), Treaty Body and the Treaty Body’s functions. In each diagram that contains an Optional Protocol, there will be a dotted line to represent the functions the Optional Protocol establishes.

‘At a glance’

Here you will be introduced to the basics of the Treaty Body:

- Name of the Treaty

- Name of the Optional Protocols

- Name of the related Treaty Body

- When the Treaty entered into force

- Where the Treaty Body is located

- How often the Treaty Body Meets

- How often States parties must submit reports

- A link to see if your State has ratified the Treaty and its Optional Protocols

- Information on the inclusion of VAW in State reports

Human rights treaty, optional protocols and the related treaty body

A brief description of the human rights treaty, its optional protocols and the treaty body responsible for overseeing states parties compliance with each.

What can the Treaty Body do?

Each page contains information related to the work of the specific Treaty Body and how CSOs, women’s rights activists and other civil society actors may engage with regard to tackling VAW. Specifically, in this section you will find information on:

- “Shadow” or “parallel” reports

- General Comments/General Recommendations

- Individual complaints

- Country Inquiries

- Urgent Procedures

- Early Warning Measures

Already familiar with the UN Human Rights Treaty Body System and the work of Treaty Bodies? Use the links on the right-hand side of this page to navigate to the specific Treaty that interests you.

Need a bit more information before diving in? See below for an introduction to international human rights law, treaty bodies and what they can do.

…the peoples of the United Nations have in the Charter reaffirmed their faith in fundamental human rights, in the dignity and worth of the human person and in the equal rights of men and women and have determined to promote social progress and better standards of life in larger freedom…

Preamble, Universal Declaration of Human Rights

The creation of the Universal Declaration on Human Rights (UDHR) marked a historic moment in human rights history. Adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on 10 December 1948, the UDHR embodied the work of representatives from all regions the globe. Under the leadership of Eleanor Roosevelt, then head of the United Nations Human Rights Commission, the UDHR established the general human rights principles and standards all States are expected to respect, protect and fulfil. And. with the continual involvement of the Commission on the Status of Women and other activists, the draft of the UDHR not only acknowledged the equal worth of every human being but the equal rights of men and women. At the age of 85, Ms. Minerva Bernardino of the Dominican Republic remembered these deliberations, stating “I am very proud to have been instrumental in changing the name of the Declaration of the ‘Rights of Men’ to the Declaration of Human Rights.”

As part of a two-pronged strategy the UDHR was to be accompanied by a legally-binding convention that would together form an ‘International Bill of Rights’. The United Nations Commission on Human Rights (now the ‘Human Rights Council’) was tasked with developing and drafting the human rights convention, outlining the specific rights and limitations all States could be bound by. At the request of the General Assembly, the convention was broken into two international human rights treaties: the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR). With the UDHR, these treaties constitute the ‘International Bill of Rights’ and establish the minimum standards of international human rights protections.

Following creation of the ICCPR and ICESCR 7 other core United Nations human rights treaties have been adopted and entered into force. Each treaty substantively expands upon the particular rights guaranteed in the International Bill of Rights with a focus on specific thematic concerns or the protection of vulnerable groups. These are:

- The International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (1965)

- The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (1979)

- The Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment (1984)

- The Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989)

- The International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families (1990)

- The International Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (2006)

- The International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance (2006)

Together, the 9 United Nations human rights treaties form the core of international human rights law.

Treaty

There are 9 core international human rights treaties: binding, written agreements between States, which create legal rights and duties governed by international law. A treaty is a formal and binding agreement between States that outlines obligations which they have chosen to accept.

They typically require a minimum number of signatories to come into force.

Note: Reservations

According to the 1969 Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, a reservation is (article 2.1d):

“…a unilateral statement, however phrased or named, made by a State, when signing, ratifying, accepting, approving or acceding to a treaty, whereby it purports to exclude or to modify the legal effect of certain provisions of the treaty in their application to that State.”

Reservations are a way for States to limit their obligations under a treaty. In effect, reservations allow a State to be a party to a treaty while simultaneously excluding the legal effect of specific provisions that treaty contains. This happens when a State issues a formal statement at the time of signing, ratifying, accepting, approving or acceding to a treaty, indicating which particular provisions they are choosing not to be bound by.

Reservations cannot be made to every provision in a treaty, however. All reservations must be narrow, specific and consistent with the overall object and purpose of the treaty – otherwise the reservation would make the ratification or accession to the treaty entirely meaningless. For example, some States parties to the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) have been allowed to launch reservations so that the laws relating to male succession of royal or aristocratic titles are not subject to CEDAW’s equality provisions. This kind of reservation has been broadly accepted without comment. However, other States have tried to file reservations which broadly reject entire articles within CEDAW, such as Article 16’s right to equality in the family. In this regard, the CEDAW Committee has emphasised that, whether lodged for national, traditional, religious or cultural reasons, reservations broadly rejecting Article 16 are incompatible with CEDAW’s object and purpose, and therefore are impermissible.

UN Treaty Bodies

UN Treaty Bodies (also referred to as a “committee” or “treaty-monitoring body”) are committees created to monitor states parties’ implementation of a specific international treaty. Under the UN human rights system, treaty bodies are established to monitor states parties’ implementation of the 9 core human rights treaties. These human rights treaty bodies consist of independent experts with recognised expertise in human rights. They are elected for fixed renewable terms of four years by states parties to the relevant treaty. Treaty bodies only have the power to address states that have ratified the treaty they are mandated to monitor.

There are ten international human rights treaty bodies (9 committees, 1 subcommittee):

- The International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination – Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination

- The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women – Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women

- The Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment- Committee against Torture

- Subcommittee on the Prevention of Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment

- The Convention on the Rights of the Child – Committee on the Rights of the Child

- The International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families – Committee on Migrant Workers

- The International Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities – Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities

- The International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance – Committee on Enforced Disappearances

Assistance is provided to the human rights treaty bodies by UN staff members and report on their work are delivered to the leadership of the UN (for example, the UN Secretary-General) or political bodies of the UN, for example, the General Assembly. These institutions within the UN may then take further action on the issues raised by the treaty bodies.

Optional Protocols

In essence, Optional Protocols (“OPs”) are treaties in themselves. These are instruments drafted and introduced for signature/ratification as supplements to treaties, but with their own provisions. OPs can provide additional capabilities to the treaty body responsible for overseeing states compliance with the relevant treaty (e.g. OP to the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women gives the Committee the power to conduct country inquiries). OPs can be agreed upon by some, or many of the states parties to the core treaty.

Like the core human rights treaties, these typically require a minimum number of signatures before they can enter into force.

Consideration of states parties’ reports

States that are party to any of the core treaties are obliged to regularly submit to the Treaty Bodies substantial reports on their implementation and adherence to the treaties.

Given that each human rights treaty derives from the UDHR, there is overlap between different treaty bodies’ provisions For example, all human rights treaties contain a provision on equality and non-discrimination. As such, states parties’ reports prepared for each relevant treaty also overlap To streamline the states parties’ reporting process, the UN has developed a harmonised reporting procedure that allows states parties’ to consolidate the required, overlapping reporting information into a single ‘Common Core Document’. This Document is submitted to the UN Secretary General, who then transmits the reports to each relevant treaty body.

In conjunction with the Common Core Document, states also prepare additional treaty-specific reports to be submitted to the relevant Treaty Bodies for review.

Shadow Reports/Parallel Reports

Recognising that states do not always paint a complete picture of the human rights context in their countries, Treaty Bodies may invite input from civil society to be used in their review of the relevant states’ report. This input is submitted parallel to the concerned states’ report. These reports are often referred to as “shadow reports” or “parallel reports”.

Parallel reports give practitioners and advocates the opportunity to include their perspective on the human rights context in their country, regardless of whether this information complements or opposes the official states report submitted to the Treaty Body. While state reports tend to provide information on legislative framework, they may not always thoroughly reflect the reality on the ground: for example, they may focus on domestic law, even though the implementation of that law for rights-holders may not be effective in practice. Civil society actors have the opportunity to conduct their own research, present alternative evidence, views, findings and/or raise issues that not covered by the state reports.

NGOs, CSOs, and other women’s and human rights organisations play an important part in creating parallel reports that more fully and comprehensively reflect women’s concerns on the ground. Importantly, these reports highlight gaps in official reports and contribute to the fight for women’s equality. The participation of civil society organizations is also important for publicising the content of human rights treaties and the outcomes of the discussions in the periodic reporting process: this is a state obligation, but often CSOs communicate very effectively at the grass-roots level.

The requirements for submitting Parallel Reports vary significantly between treaty bodies.

General Comments/General Recommendation

Article 31 of the 1965 Vienna Convention on Law of Treaties recognises that treaties need continuous contextual interpretation. This is to ensure the provisions within a treaty remain relevant in modern contexts and continue to fulfil their object and purpose.

Treaty bodies have the power to issue General Comments/General Recommendations as continual contextual interpretations of their relevant treaties. These can be used to clarify states’ report obligations (e.g. requiring information on a specific issue must be included in reports) or to suggest approaches to implementing treaty provisions. They can also be written as interpretations and updates of the human rights treaty, often clarifying the meaning of specific provisions or highlighting thematic issues relevant to the treaty. In other words, they provide orientation for the practical implementation of human rights and form a set of criteria for evaluating the progress of states in their implementation of these rights. For example, the Committee on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination has made 33 General Recommendations to clarify and expand various thematic issues related to women’s rights and gender equality. These include:

- Violence against women (General Recommendation 19)

- Temporary special measures, including quotas (General Recommendation 25)

- Women’s access to justice (General Recommendation 33).

General Comments are not treaties and do not need ratification by states parties. Strictly speaking they are not legally binding, however they are considered authoritative statements on the content of legal duties assumed by states parties.

Individual Communications

Any individual who believes her rights under a treaty have been violated by a states party (to the relevant human rights treaty) may be able to bring a communication before the related Treaty Body. In fact, thousands of people from around the world do so every year, provided that their state has ratified/acceded to the relevant treaty and recognized the competence of the Treaty Body through a formal declaration. It is through individual complaints that human rights are given concrete meaning. In the adjudication of individual cases, international norms that may otherwise seem general and abstract are put into practical effect. When applied to a person’s real-life situation, the standards contained in international human rights treaties find their most direct application. The resulting body of decisions issued by Treaty Bodies may guide States, NGOs/CSOs and individuals in interpreting the contemporary meaning of the treaties concerned.

With written consent from victims, complaints may also be brought by third parties on behalf of individual. In certain cases, there is also the possibility that a third party may bring a case without such consent, for example, where a person is in prison without access to the outside world or is a victim of an enforced disappearance.

Some Committees may, at any stage before the case is considered, issue a request to the states party for “interim measures” in order to prevent any irreparable harm to the author or alleged victim in the particular case. Typically, such requests are issued to prevent actions that cannot later be undone, for example the deportation of a woman facing a risk of torture, including facing “honour killing” by family members, or if a child faces a risk of FGM if she is returned to her native country. A decision to issue a request for interim measures does not imply a determination on the admissibility or the merits of the communication but it must have a reasonable likelihood of success on the merits for it to be concluded that the alleged victim would suffer irreparable harm. If the complainant wishes the Committee to consider a request for interim measures, he/she should state it explicitly, and explain in detail the reasons why such action is necessary.

Want more? Visit the OHCHR’s page on individual communications

Country Inquiries

Some treaty bodies may, under certain conditions, initiate country inquiries if they receive reliable information containing well-founded indications of serious, grave or systematic violations of the conventions in a state party. For example, two recent CEDAW inquiries were brought based on reports supplied by local NGO/CSOs:

Early Warning Measures

Early Warning Measures can be taken by certain Treaty Bodies to prevent existing problems from escalating into conflicts. These can also include confidence-building measures to identify and support any action that improves the livelihood of the concerned group and prevents a resurgence of conflict where it has previously occurred.

Criteria for early warning measures could, for example, include the following situations:

- Lack of an adequate legislative basis for defining and prohibiting all forms of racial discrimination, as provided for in the Convention

- Inadequate implementation of enforcement mechanisms, including the lack of recourse procedures

- The presence of a pattern of escalating racial hatred and violence, or racist propaganda or appeals to racial intolerance by persons, groups or organisations, notably by elected or other officials

- A significant pattern of discrimination evidenced in social and economic indicators

- Significant flows of refugees or displaced persons resulting from a pattern of racial discrimination or encroachment on the lands of minority communities

Urgent Action Procedures

Urgent Action Procedures allow certain Treaty Bodies to respond to problems requiring immediate attention to prevent or limit the scale or number of serious violations of the Convention.

Criteria for initiating an urgent procedure could include, for example (see the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination):

- The presence of a serious, massive or persistent pattern of racial discrimination

- A serious situation where there is a risk of further racial discrimination