As South Korea flexes its muscles as an aid donor, LSE’s Justine Pak evaluates the influences at play in the way the East Asian nation distributes its Development Assistance.

It is remarkably easy to view humanitarian aid as a primarily Western phenomenon, but as the world’s economic powerhouses move eastward, there is good reason to re-examine how aid relationships are understood and analysed by the international community.

One such country is South Korea, which transformed itself from one of the poorest countries in the world after the Korean War, to one of the world’s top 15 economies. In fact, South Korea recently became the first official aid recipient to become a donor nation.

South Korea’s surprise performance in the 2002 football World Cup on home soil, where it advanced to the semi-finals before losing to Germany, has led to a national obsession with the tournament. Since 2002, the World Cup has provided a quadrennial stimulus for local and national businesses. More recently, it has given major conglomerates the opportunity to transform a national campaign into a global cause.

In an attempt to tap into the Team Korea fervour during the 2010 World Cup in South Africa, telecommunications and wireless service provider Olleh KT participated in a campaign called “Red Shirts Make a Better Place” (Korean: “티셔츠의 기적”).[1] Several major corporations, including Samsung, Hyundai and LG sponsored outdoor screenings of the matches around Seoul, and distributed t-shirts and other game-related freebies to viewers. Olleh KT’s vision was that people would wear the shirts throughout the match as a form of advertising, and afterwards, donate them to someone in need.[2]

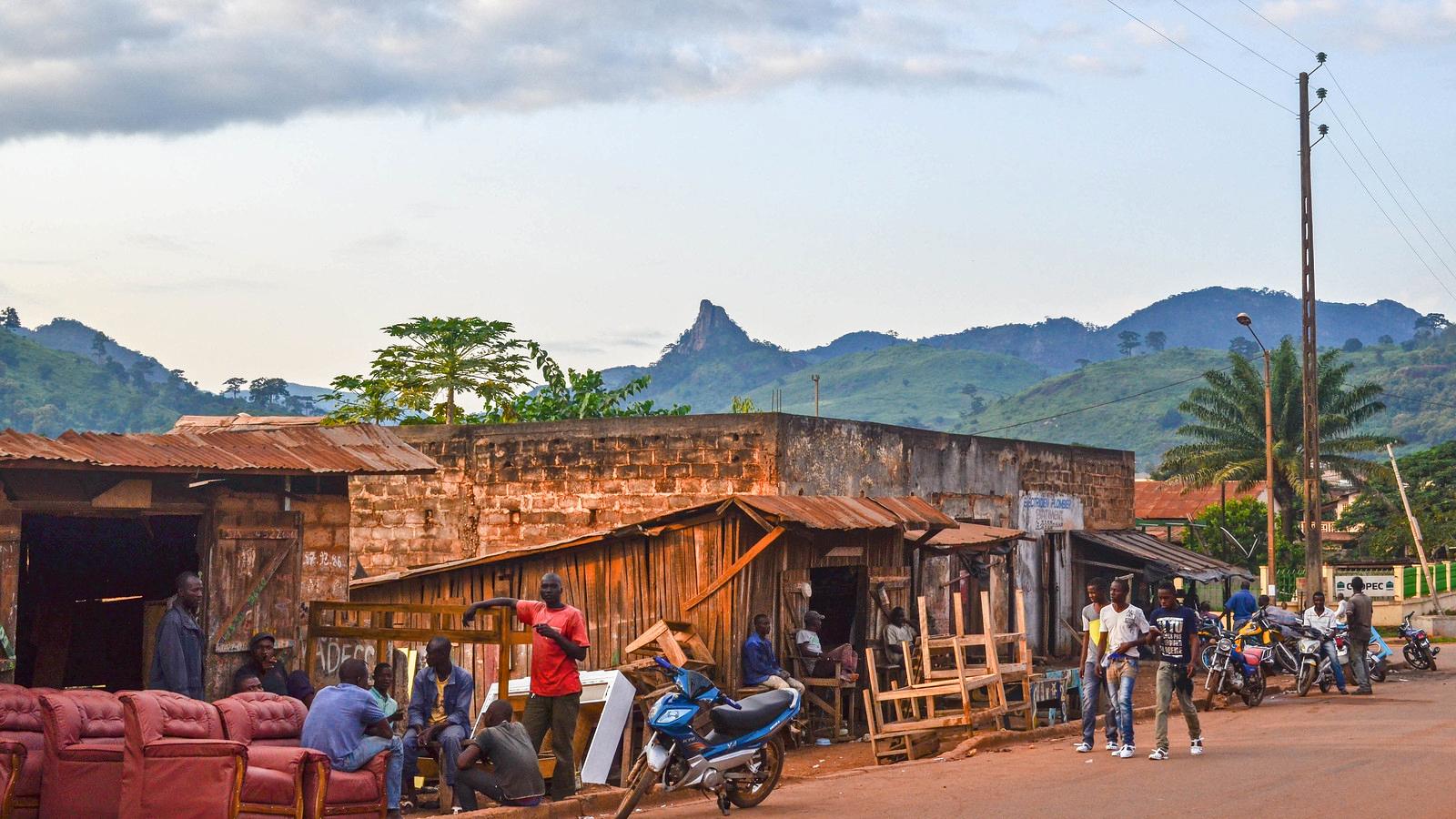

According to the publicity campaign, the recipients of these t-shirts would be poor needy children in Africa. The goal of the campaign was to bring to life the maxim “giving someone the shirt off your back”. Organisers hoped that football fans across the world would sponsor similar campaigns in their home countries, resulting in a rainbow of coloured shirts moving en masse for children in need of clothes.

While this campaign seems harmless, generous, and, given the World Cup’s location that year, timely, it triggered a debate on economic efficiency (the cost of shipping to Africa versus donating money to relief organisations) and the value of donating a product that may not actually be high on the local “needs priority list,” South Korea is not the only, or indeed, the first country to host this kind of campaign. Giving as a general modus operandi has been covered in great detail by Western and Korean organisations alike.[3] Our Development Alternative, like many aid counterparts in other countries, has called into question the responsibility of donor agencies and nations to be responsible, conscientious, and practical in giving.

The aim of this article is not to question South Korea’s method of giving, but the process by which countries choose to distribute their aid. There remains in South Korea a strong socio-cultural correlation between “Africa” and “need,” a connection that is reinforced by the messages these organisations send to the donor public. UNICEF Korea, Save the Children Korea, and World Vision Korea all have a strong public presence in South Korea, but their focus is not on Asian issues per se, but rather on those farther away- namely Africa and South America. According to Global Humanitarian Assistance, in 2010 South Korea gave nearly US $1.2 billion dollars in aid. Sub-Saharan Africa received 47.9% of that assistance; the second largest recipient group was South America with 18.3%.[4]

It is easy to write off the red shirt drive as a one-time project to benefit African children, but massive participation in the World Cup donation campaign, as well as major NGO advertisements seem to reflect otherwise. More curious, and perhaps more worrisome, is South Korea’s seeming ignorance of both domestic issues and those closer to home in neighbouring Southeast Asia, China, and Tibet. Unfortunately, it is possible that high-profile Korean NGOs choose to avoid highly-politicised issues – such as North Korean refugee relief and famine aid. African and South American needs may be far enough away to extend assistance while avoiding political entanglement. The reasoning, however, may be more than political.

Could South Korea simply be following global trends in aid distribution, or is she exerting a certain degree of national agency within this greater framework, one not dissimilar to the Social-Darwinist patterns of the West’s past? The red shirt episode in 2010 highlights South Korea’s place in the globalisation of aid, and the barely acknowledged fact that Western nations are not the only “givers.” But what has globalisation done for humanitarian aid? The transversal of need, especially when laced with inferences of racial superiority, has vastly different implications in a newly global context, especially for Asian nations like South Korea, whose adoption of certain campaign strategies mirror their Western counterparts in more ways than is often acknowledged. What may be at stake is more than mismanaged donations or avoidance of politically-tinged global hot spots. As aid becomes a global activity, outdated stereotypes of the “haves” and “have-nots” may also follow.

[1] Olleh KT Commercial: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DKVM8fSE9YE

For You and For Me Olleh Website: http://foryouandforme.tistory.com/24

If it were major corporation in S.Korea that were giving this form of indirect aid, then perhaps it is just a part of their CSR policy. CSR is now expected to some extent for major MNCs. It would be interesting to see if it is the corporations who are leading this aid initiative or if it is from the government or people etc.

Very interesting points you have noted, regards for putting up.