Holly Porter & Rebecca Tapscott[1] examine the operation of security groups in Gulu, northern Uganda.

Last November, at three in the morning, a man was murdered on the street not far outside Gulu Town. There were tens of witnesses, yet there was no investigation, no prosecution, and no compensation provided to the victim’s family. A common reflection on the event was that the victim “did good to die”.

People recount the story in different ways: one version describes the victim as a notorious and unrepentant drug dealer and crook. On the night he was finally caught, a mob of frustrated neighbours banded together and beat him with a machete, resulting in his unintentional, if not surprising, death. Another version explains that the murdered man was a petty thief and marijuana smoker who made enemies with a community leader. That night, he either burnt the kitchen of the leader or was framed for arson. The more powerful man responded immediately, taking the law into his own hands and brutally murdering the victim in public, thereby asserting authority over the jurisdiction.

Such stories of people taking justice “into their own hands” are common in northern Uganda. This particular instance happened just outside Holly’s house. In the past two weeks, as we have looked closer at local responses to community insecurity, people have recounted other recent events of citizen-driven violence. Among these stories, there is wide variation in the victims’ personal details (professionals to lay-people, men and women, adults and youth) and originating crime (theft, prostitution, over-drinking or drug abuse, violating curfew, etc.). Some can be categorized as “mob justice” or “mob violence”— they share a collective, spontaneous, and potentially fatal, beating.

Other events seem less unanimous and spontaneous. In some cases individuals manipulate the norm of collective violence to pursue personal vendettas and may act through or under the guise of impromptu community sanction. For example:

- A village leader had an ex-girlfriend beaten in the street and eventually arrested for prostitution because he saw her interacting with another man.

- A man was sitting with a friend outside his house, on his property, when a group of men came and arrested him for drinking alcohol late at night. It later emerged that one of the group members and the arrested man were rivals for the same woman.

- A spate of house burnings occurred last year. Those targeted were mostly suspected or known sex workers. “Disappointed” or rebuffed men torched the women’s homes.

Minor extortion and theft by these security groups is an extremely common anecdote.

Many have written about similar phenomena in northern Uganda: Tim Allen reflected on the executions of witches in neighbouring districts as a violent method of community healing, analogizing them to the removal of a cancerous growth for the wellbeing of the larger body.[2] Ben Mergelsburg documented the gang-like organization of youth into security groups in the Pabbo IDP camp during the war. The groups successfully improved the relative security of average camp members while grossly infringing on basic freedoms such as privacy and movement.[3] Similarly, in some of her earlier work, Holly found that different responses to crime (including mob justice) amongst Acholi reveal a deep distrust of the central state’s institutions to dispense justice, as well as a shared desire to protect Acholi moral order (e.g. “social harmony”) above individual interests in the aftermath of crime.[4] Social harmony often requires victims to cope using extraordinary forgiveness, engaging in ritual cleansing, or even by ignoring the initial violation, as was the community’s response to this instance of killing. In other situations, such as those related to the insecurity that emanates from high levels of crime, norms are protected with brutal and expeditious punishment—i.e. mob or citizen-driven “justice”.

Additionally, literature on vigilantism, community policing, and “twilight” or “boundary” institutions is relevant. David Pratten writes about Nigerian popular justice, where the federal government encouraged local government to legalize vigilante groups which discipline the community through a range of physical and psychological punishments. He explores how these groups insert themselves into judicial, as well as economic and political strategies, both influencing and being influenced by cultural norms and expectations.[5] Many others provide analyses of the complex relationship between state policing institutions and community security groups.[6] Christian Lund in particular explores vigilantism as a set of “twilight” or “boundary” institutions which take on state-like responsibilities or symbols, challenging the distinction between what is state and what is not.[7]

The November murder is particularly worthy of attention because it is directly associated with the inauguration of community security groups in the parish. It is believed that members of the security group were present at the scene of the murder; however, they have actively distanced themselves from the event, employing narratives of collective citizen violence and mob “justice”. Thus, the formation of security groups is presented as an answer to insecurity, including incidents ranging from petty theft to the respondent mob violence, in the absence of police or state action. Communities and their leaders leverage these very events to justify the creation of local security groups.

This piece centres on the recent creation of security groups in this very parish, comprised of four villages. Our initial research suggests that experiences here seem similar to other village-level security groups.

The initiative to form security groups appears to have been catalyzed by a few powerful men in one village who wanted to crack down on crime. Their work began ad-hoc, targeting a few known thieves and marijuana smokers/growers.[8] The main initiators recruited a combination of upstanding citizens and (presumably reformable) criminals. Like most of the population of northern Uganda, many of these men spent their formative years living in the midst of conflict, being witness to and even participating in the gruesome history of LRA and UPDF violence. Those selected were then officially nominated and “elected” (perhaps more accurately “approved”) by those residents in attendance at the community security meeting.

These young men were then charged with the maintenance of security and the enforcement of community bylaws, approved in the same meeting. While their official duty is to enforce these bylaws, many have adopted an expansive interpretation of their roles, assuming the mantel of guardians of a vision of community morality. Some have emphasized counselling and sensitization for topics like domestic violence disputes, alcoholism, indecent dress, witchcraft/wizardry, adultery, and negligent parents.

In November 2013, two weeks after the group began patrolling, a government representative called a security meeting for the parish, comprised of the initiating village and three others. The government representative presented the originating security group as a positive exemplar of local security, and charged each village to create their own security group and by-laws, thereby formalizing and officially sanctioning the groups with authority from the central government. Although little has materialized, the government has promised to provide training; members of the security groups, along with their leaders, wait impatiently for this and other symbolic investments, like identity cards and raincoats.

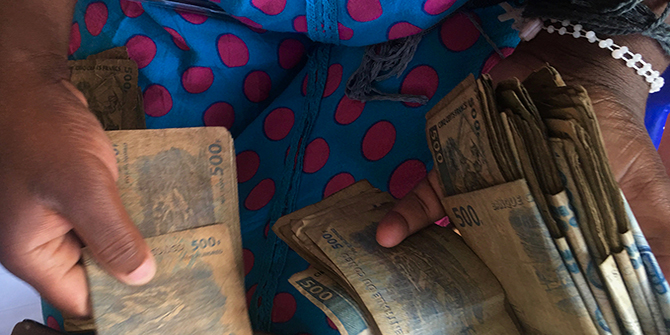

Since their official launch, the groups patrol regularly. Each village has also instituted bi-monthly or quarterly community security meetings in which the security group reports on their activities, and residents can raise concerns, give feedback, and contribute to the group (equivalent to 25 pence per household per month—the same amount that a resident pays for water). The security groups also collect fines for infractions against written or unwritten bylaws. For the initial group, the bylaws include, as paraphrased/summarized by us:

- Those who perpetrate crimes must both pay compensation and receive punishment (usually in the form of caning).[9]

- Protecting or hiding a suspected criminal is punishable by complete destruction of home and expulsion from the community.

- Idle or disorderly behaviour, selling alcohol, allowing minors to enter video halls, and theft and drug dealing (with an emphasis on marijuana) are punishable by caning and fines between 5 and 15GBP. Youth guilty of these acts will be punished before their parents and the community.

- Proper sanitation facilities (latrine and rubbish pit) must be present at each household. In the absence of proper facilities, the security group will build them and charge the transgressor up to 25GBP for their labor.

- It is necessary to participate in community work related to cleaning and sanitation. Refusal to participate is punishable by a fine of 1GBP.

- Indecent dress is punishable by a minimum of 10-20 strokes of a cane.

- Capital offenses will be arrested and handed over to the police.

There are additionally clearly strong gender dimensions of the bylaws and how they are enforced, as evidenced in the examples of individual action provided above. This could be interpreted as an emphasis on social harmony or Acholi moral order, as described by Holly, or a struggle between modernization and women’s rights on the one hand, and existing power structures on the other.

Many of the groups also have a set of process rules. This particular group emphasized that only those with good morals who are well-known in the community should be permitted to join the group, and that they should work within their jurisdiction. Other groups require that security members arrive to night patrol on time, sober, and wearing gumboots and dark clothing. All the groups we looked at require the security group to report to the LC1 on their activities. These internal rules, along with their relation to local government leaders, place them at the boundary of state institutions.

Community members and leadership simultaneously lament what is seen as an excessive use of violence by the group, while praising the group’s success in improving security in their communities. For example, an elderly woman in a regular community security meeting that Holly attended urged the group to beat men who wear their trousers too low and not just girls who where skirts above the knee. Her admonition was met with energetic applause. Others in attendance expressed concern about the potential for and the instances of excessive violence, as well as the security group’s lack of concern for determining guilt, resulting in a conflation of suspect and perpetrator. In a way, this conflation seems at home in an environment where people frequently describe criminality in terms of status: a “wrong” or “bad” person (labal), as opposed to a specific act of transgression and attending evidence. On the other hand, people are well aware of how this attitude towards criminality regularly results in punishments for innocent community members who find themselves in the wrong place at the wrong time. Interviewees have said that those caught at night should be punished during the day and “in the light”—when the community can observe, enforcing transparency and accountability—rather than “in the dark”.

Objections voiced about the groups have been explicitly and implicitly quashed: protesting community members have been removed from meetings, and leadership has threatened any citizens who do not support the security group with future acts of retribution and social sanction. The promise of withdrawn security in a situation of significant insecurity leaves the complainant vulnerable to almost certain future crime.

At a micro level, the formation of this security group has been presented as a response to an untenable security environment, evidenced through mob violence and the crime that inspires it. Community security groups are engaged to weed out the “bad elements” or “wrong people” in the community to bring society back to order. Community policing and security groups have been and continue to be formed across the Acholi sub-region. And it’s not just a local effort: in Uganda, there have been international interventions to support the formation of community policing groups since the 1990s, as a part of an agenda to decentralize government services.

This raises the question: are the wealth of critiques that arise from the above description of community security groups simply a re-hashing of the risks of decentralization of other services, like health, education, and even governance; or, is there something qualitatively different about community management of violence and security?

While decentralization is lauded as a method to improve provision of and access to services by putting them closer to the end-users, a number of critiques are common that may also be applicable to the decentralization of security in the form of community policing. These include issues such as the technical challenges of decentralization, as well as the risk that it will undermine the power and legitimacy of the state. Undermining state legitimacy may be an especially significant risk given the creation of extremely localized bylaws.

Additionally, decentralization of basic services can be seen as a withdrawal of the central state. Without local capacity and access to resources local administrative provision of services can actually erode the provision of services. In sectors like water, sanitation, health, and even education, this local and state governance “failure” can be an entry point for aid and development organizations, which present a project or program to fill the gap. The case of security, however, seems to call for a different response: rather than taking over the service (e.g. policing) and striving to create local ownership or a private supply chain as is frequently done in other sectors, interventions for security defer to the central government to establish lines of reporting and responsibilities for local initiatives. That is, unlike with other sectors, the donor cannot bypass the state for administrative control over security without directly threatening the presumption of the state’s monopoly on power. International administrative responses to weak security (e.g. the use of force to control the use of violence) are less feasible as they would be understood to be direct infringements on state sovereignty. This may, in effect, increase the state’s administrative control without dramatically improving security.

It is in this space that burgeoning citizen-driven initiatives begin the processes of institutionalizing violence. However, given the very nature of this space, these organizations are, by necessity, “boundary” or “twilight” institutions, in constant negotiation with the actors and institutional forms of the central state. Continued study should provide important insights into how violence and coercion relate to state formation, governance, and security.

This post originally appeared on the Justice and Security research blog.

[1] For the purpose of clarity, reference to either of the authors is done in the third person.

[2] Allen, Tim. 1999. “Violence of Healing”. Sociologus, New Series: 47(2): 101-128.

[3] Mergelsberg, B. 2012. “The displaced family: Moral imaginations and social control in Pabbo, northern Uganda”. Journal of Eastern African Studies 6 (1): 64-80.

[4] See Porter, Holly E. 2012. “Justice and rape on the periphery: the supremacy of social harmony in the space between local solutions and formal judicial systems in northern Uganda”. Journal of Eastern African Studies 6 (1): 81-97; and Porter, Holly E. 2013. ”After rape: Justice and social harmony in northern Uganda”. Ph.D. Thesis. London School of Economics and Political Science.

[5] Pratten, David. “Singing Thieves: History and Practice in Nigerian Popular Justice.” In Global Vigilantes, edited by David Pratten & Atreyee Sen. Cambridge University Press: New York (2008): pp. 177.

[6] Heald, Suzette. “State, law, and vigilantism in northern Tanzania”. African Affairs 105.419 (2006): 265-283; Jarman, Neil. “Vigilantism, Transition and Legitimacy: Informal Policing in Northern Ireland”; Kyed, Helene Maria, “State Vigilantes and Political Community on the Margins in post-War Mozambique”. In Global Vigilantes, edited by David Pratten & Atreyee Sen. Cambridge University Press: New York (2008).

[7] See, for example: Lund, Christian. “Twilight institutions: an introduction”. Development and Change 37.4 (2006): 673-684. and Buur, Lars. “Reordering society: vigilantism and expressions of sovereignty in Port Elizabeth’s townships”. Development and change 37.4 (2006): 735-757.

[8] These identities or accusations are frequently conflated—such individuals are also referred to as “bad elements in society” or “wrong doers”.

[9] This bylaw does not specifically relate to theft; however, it is probably meant to address this concern.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the Justice and Security Research Programme, nor of the London School of Economics.

______________________

Holly Porter is the lead researcher for northern Uganda for the JSRP. Her research focuses on gender, sexual violence, social healing and local notions of justice, particularly on women’s experiences after rape in northern Uganda, where she has worked since 2005. She holds a PhD in International Development from the LSE.

Rebecca Tapscott is a PhD student at the Fletcher School at Tufts University, studying boundary institutions and governance in fragile states. Her previous work focuses on gender, social norms, and norm change, as well as community-based development initiatives in sub-Saharan Africa.