Celeste Hicks explores the trial of Hissène Habré and what it could mean for future justice and accountability efforts in Africa.

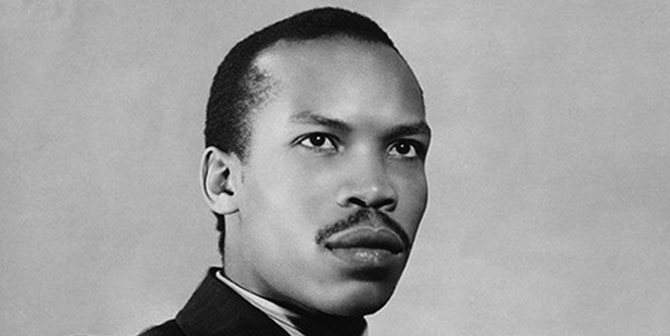

The legal vagaries and judicial details of the Extraordinary African Chambers (EAC), which sentenced Hissène Habré to life imprisonment in 2015, was not at the top of the list of concerns of many of the former Chadian president’s victims. What matters most was the EAC’s success in reaching a guilty verdict on charges of war crimes, crimes against humanity and torture on a remarkably tight timeframe and on a budget of just over 8 million euros.

However, for wider African justice, the EAC’s status as an ad hoc hybrid court established inside the existing Senegalese justice system is significant. There were a lot of firsts: it was the first time that the African Union (AU) had established a court; the first time a former African head of state had been tried before a court in another African country; and the first time a universal jurisdiction case had proceeded to trial in Africa. Being founded at a time when many legal analysts had largely concluded that hybrid trials would soon cease to be relevant, the EAC was part of something like a re-birth in hybrid justice. Although the EAC has been described as residing ‘at the limits’ of what a hybrid trial could be because only a handful of its officials were not Senegalese, it was widely praised for its status as an ‘African’ hybrid court. In practice, this meant the judges, defence and prosecution teams were all African and, significantly, the Chadian victims were allowed representation through the forming of ‘civil parties’ to the litigation, mostly organised by Chadian lawyers.

The EAC thus provides us with some interesting lessons as attempts are now being made to set up similar hybrid trials in other African countries. As efforts to establish a court for South Sudan have been delayed by political blockages and the fact that political violence there has not yet ceased, the EAC has shown us how a court could be established in another country — in this case Senegal where Habré had sought exile in 1990. Basing the trial in Senegal defused some of the political tensions which could have been stoked by attempting to hold a trial in Chad itself, and removed the need to extradite him abroad (possibly to Europe).

As momentum builds behind efforts to establish a hybrid trial to investigate human rights abuses in Central African Republic (CAR), the EAC’s failure to secure the extradition of five co-accused former members of Habré’s secret police also provides valuable learning opportunities with regards to how to choose who to prosecute. In the CAR there may be many thousands of individual perpetrators, and the EAC has created much food for thought about the relative merits of going for the top leadership or middle level officials who may have been more involved in the day-to-day acts of torture.

Among the situations being most closely watched today is that relating to the former president of The Gambia, Yahya Jammeh, who fled into exile in Equatorial Guinea in early 2017 after losing a presidential election and negotiating his departure with regional powers. Reed Brody from Human Rights Watch, who played a major role in bringing about Habré’s trial before the EAC, has already met victims of alleged human rights abuses under Jammeh and has expressed an interest in using a similar approach in bringing a prosecution. There are certainly parallels to the Habré case, with Equatorial Guinea seeming to offer the former president a similar kind of protection that the Chadian leader enjoyed for more than ten years under Abdoulaye Wade in Senegal. Yet while the use of universal jurisdiction (a so-called ‘unique pillar’ of the EAC) is unpopular with many African heads of state in Africa, it could in theory be used to secure Jammeh’s extradition.

The EAC had a number of other important impacts relevant to future attempts to hold perpetrators of atrocities to account. For the first time, the outreach programme was run by an independent consortium. A significant ten per cent of the overall budget of the court was dedicated to making sure its work was understood in Chad itself. In addition, although the initial charge sheet neglected to specifically list crimes involving sexual violence (of which there were many), after dramatic accusations during the witness phase that Habré himself had raped one of the victims, the presiding trial judge took the unusual step of amending the original charges to include sexual violence. This helped to re-focus the legal community’s attention to the issue, and has been welcomed by campaign groups.

Of course, the EAC did not succeed in everything. The failure to secure the extradition of the five co-accused, five top agents in Habré’s Direction of Documentation and Security, did not go down well in Chad itself where many ordinary people are still questioning where the responsibility for everyday torture in the prisons of the 1980s truly lies. This was compounded by Habré’s stubborn vow of silence during the trial and his refusal to co-operate in any way with his court-appointed defence team. In addition, the EAC neglected to investigate the role of international powers, specifically the US and France, in facilitating Habré’s rise to power through the covert supply of intelligence and weapons via the CIA. Finally, the EAC has also made little progress in securing contributions to a Trust Fund for victims which was mandated during the Appeals phase — although $5 million was recently committed to the Trust Fund by the African Union. This is only a fraction of the 81m Euros ($100m) ordered by the EAC judges.

In the aftermath of Habré’s conviction, the AU were keen to promote the success of the EAC and a roundtable event was held at the AU summit in 2017 exploring how the reputation of the trial as an ‘African solution to African problems’ could be built upon. While it still appears true that the most important reason why a prosecution eventually goes ahead would be that the conditions are right and a trial becomes politically acceptable or even desirable (in this case Habré had been out of power for 25 years and abandoned by his erstwhile supporters), the story of the EAC nevertheless offers us an example of a tenacious effort to bring about a trial which, through its status as an ‘African’ hybrid court, allowed it to become acceptable in many parts of the continent.

This article was first published on the Justice in Conflict blog.

Celeste Hicks (@ChadCeleste) is a freelance journalist focusing on Africa and the Sahel. She was a BBC correspondent in Chad and Mali from 2008-10. The Trial of Hissene Habre – How the people of Chad Brought a Tyrant to Justice is her second book.

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and in no way reflect those of the Africa at LSE blog, the Firoz Lalji Centre for Africa or the London School of Economics and Political Science.