The DRC’s new president brings opportunities to rethink development in the Great Lakes region. With current aid policies charged with fuelling political instability, Léopold Ghins argues the status quo is unable to bring prosperity and effective peacekeeping.

Despite decades of foreign interventions, both through peacekeeping and aid, the African Great Lakes remain one of the world’s most fragile regions. So how can we understand the failures of the UN and donors in the area? The question is particularly relevant in view of the recent and contested inauguration of Félix Tshisekedi as the new President of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

While observers diverge on whether the presidential change enhances the country’s prospects, such a major political event certainly calls for a renewed debate on the future of development and peace in the Great Lakes, and on the roles of outsiders therein.

Several studies point to the erroneous perceptions of outsiders to explain why their interventions have been unable to address the root causes of conflict in the Great Lakes. However, few authors focus on the impact of UN and donor ground-level activities on regional fragility. It is chiefly through these activities that outsiders may have become part of the problem they seek to resolve.

A first way in which outsiders could be exacerbating regional fragility is through unbalanced aid allocations. From 2003–16, Rwanda received about 130 and 50 per cent more aid in per capita terms than the DRC and Burundi respectively. The country was dubbed a ‘donor darling’, while the DRC and Burundi were considered ‘donor orphans’. In the case of Rwanda aid is largely said to have contributed to growth.

In contrast, lower aid levels have gone hand in hand with very modest economic performance in Burundi, and the persistent political crisis is wiping out the small gains of the quieter 2005–15 period. In eastern DRC, low aid levels are consistent with the prioritisation of stabilisation through the costly Mission des Nations Unies pour la Stabilisation en République démocratique du Congo (MONUSCO). Meanwhile, per capita GDP in eastern DRC has barely progressed since the 1980s.

There are two issues with the contrasting development and security trajectories that donors have contributed to induce. First, in addition to being a development champion, Rwanda is now a regional hegemon. The country has a history of meddling in the eastern DRC region, first through direct military involvement during the Congo Wars and then by supporting anti-government rebel groups such as the M23 from 2012–13. Although the West has at times pressured Rwanda to stop supporting Congolese rebels, Kagame’s successes reduce his incentives to collaborate with DRC authorities and work in favour of peace in the region. The country tends to remain hawkish on eastern DRC issues even though, as argued by Jason Stearns, ‘it is not clear that Rwanda would benefit less if there were stability’.

A second by-product of donor policies is the core-periphery structure that has emerged in the Great Lakes. At the core is the Kigali-Kampala axis, with eastern DRC, Burundi and, to some extent, North-Western Uganda together forming the periphery. People living in the core face lower security risks and have higher incomes in comparison to those in the periphery. This situation has entrenched the notion that areas in the periphery are ‘lagging behind’, and reinforces perceptions of Congo as ‘an inscrutable and un-improvable mess‘. In short, international aid policies played a part in expanding some of the economic and political divisions of the Great Lakes region.

The undesirable effects of MONUSCO are another channel through which outsiders may be aggravating regional fragility. The presence of large numbers of UN personnel in towns like Goma have created dual labour markets for cooks, cleaners and drivers. High expatriate salaries led real estate prices to plummet. Because of MONUSCO, Kinshasa has limited incentives to expand its military capacity in the east.

On the other hand, by protecting the main urban centres, MONUSCO bases prevent any armed group in Kivu and Ituri from overpowering others. Even if the UN mission plays an essential role in civilian protection, it could also be ‘condemning’ myriad rebel formations to coexist indefinitely. Not only does MONUSCO divert resources away from productive foreign investments in the Congolese economy, but it also distorts local markets and might impede on the kinds of ‘autonomous recovery’ processes that conflicts are sometimes found to induce.

Beyond the adverse effects of aid and MONUSCO, the manner in which the UN and donors connect with local actors is also of prime importance. How intervention relates to violence depends on the complementarities between insider and outsider strategies, which can perpetuate the ‘status quo’.

The genealogies of ruling parties in Burundi and Rwanda have largely contributed to shape their relations with outsiders. Donors, for their part, see Rwanda as a useful reservoir of development success stories, and bashing Burundian authorities is a cheap way to project a pro-human rights image. In eastern DRC, the security status quo enforced by MONUSCO prevents rebellions from spinning out of control, which lets regional elites carry on with the plunder of natural resources. In turn, the international community does not oppose the status quo as it wants to avoid the disturbances and humanitarian costs that a third Congo war would provoke.

The behaviour of the UN, donors and local elites together interact within a regional ‘assemblage’ or – to use Mary Kaldor’s terminology – a ‘political economy of war’ which produces the path dependencies in which the region has been engulfed for so long.

A main implication here is that there could be better ways for outsiders to achieve their goals in the Great Lakes. Studying the pathways and interactions through which UN and donor activities impact on regional fragility helps identify the causes of unintended consequences. Understanding the failures of interventions through a ‘political economy of war’ lens is also fundamental for them to be appropriately reformed.

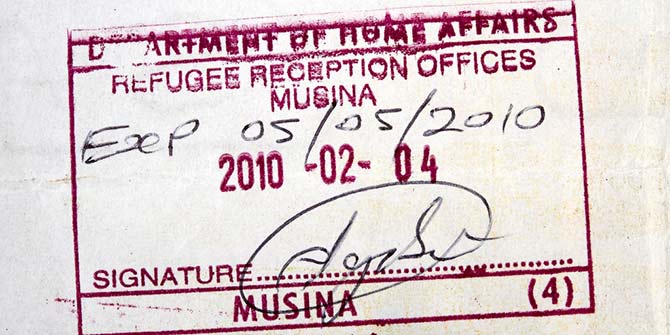

It is even more relevant in the current context of increasing fragility, and the security landscape in the Kivu and Ituri provinces is hardly sustainable, as the constantly increasing numbers of refugees and displaced persons in the region reveals. Rwanda’s authoritarian development policies have kept internal tensions in the country alive and well.

The election of Tshisekedi is an opportunity to bring intellectual fresh air to the debates around development and peace in the Great Lakes. Fragile regions deserve better than stagnation and violent status quos. International actors should learn from their mistakes to avoid creating islands of economic growth or introducing costly peacekeeping missions. They may bring short-term relief but not sustainable peace.

Léopold Ghins (@LeopoldGhins) is a policy analyst and researcher whose interests focus on governance, economic empowerment and aid interventions in fragile regions. He has previously worked for the FAO and the World Bank, including on Burundi and Rwanda. He currently works at the OECD.

Photo credit: Reuters/Thomas Mukoya

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and in no way reflect those of the Africa at LSE blog, the Firoz Lalji Centre for Africa or the London School of Economics and Political Science.