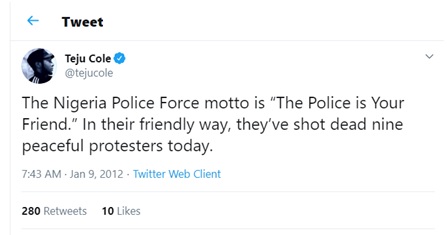

The Nigerian police’s motto, The Police is Your Friend, intends to remap perceptions of state violence at the fore of the youth-led #EndSARS protests. While highlighting the transformative potential of social media, protesters also brought into focus the ways in which the Nigerian postcolonial state abuses citizens and estranges them through acts of violence. But if not a friend, is the state an enemy or a stranger?

The #EndSARS protests in Nigeria invite us to rethink the famous motto of the Nigerian Police: The Police is Your Friend. While #EndSARS was generated by structural issues and produced several meanings, it was in large part a citizen-led social media campaign against police brutality and violence in Nigeria which was, for several weeks in October 2020, the top-trending topic globally on Twitter, drawing support from Hillary Clinton, Joe Biden and celebrities around the world. With Amnesty International calling for investigations into unjust killings of protesters at Lekki, a major hub of the protest in Lagos, and Nigerian state officials targeting many of #EndSARS promoters after denying involvement in these nefarious acts, we are confronted with the conceptual implications of an avowed friendship between the postcolonial state and citizens whose daily encounter with state agents, as the Lekki shootings have shown, is an unending song of the precarious and tragic.

The Police is Your Friend, which was itself part of a rebranding response to public perceptions of police as a foe, may then be seen as a rhetorical strategy that commands sociation, which attempts to remap perceptions of state violence. Through the online protests, we come to see that The Police is Your Friend misreads how friends are ‘called into being by the pragmatics of co-operation’, something policing in Nigeria desires of citizens but also undermines through its own brute display of force and vindictive imposing of fear on citizens. The affirmation of friendship is itself pertinent, as it ironically offers what should be self-evident as a condition for public trust.

The enunciation of friendship marked by The Police is Your Friend also means we examine the Nigerian state through an analytical frame that recollects Bauman’s phenomenon of strangerhood. ‘There are friends and enemies. And there are strangers,’ Bauman writes. ‘The stranger disturbs the resonance between physical and psychical distance: he is physically close while remaining spiritually remote.’ The stranger represents an incongruous and hence resented ‘synthesis of nearness and remoteness’ . The paradox is evident in the assertion of friendliness by state agents who give reasons to mistrust the state. To accept the friendship of the state is both to misrecognise the troubled morality that undercuts its exercise of power and to refute the perspective of the postcolonial state as a site of estrangement.

This idea of the postcolonial state in Africa as a stranger is prominent in a section of Tejumola Olaniyan’s writings, in which he imagines the postcolonial state constructed by modernity as a site of aporia, imposed strangeness and oppressive illusion. Following from Bauman, he notes that productively reshaping the state in Africa demands encountering it as ‘a stranger,’ rather than as a friend or even an enemy. Olaniyan calls for a neutral, unprejudiced starting ground that enables us ‘to come to terms with the stranger, the postcolonial state in Africa’:

‘The stranger is seen and known, but is neither friend nor enemy. Such an attitude takes state estrangement as neutral normative, and procedurally demands a valiant suspension of our admittedly justified—because experienced—prior assumptions of state enmity or friendliness in the fulfillment of its obligations and in the staking of claims by citizens.… Whether as citizen, scholar, politician, or state agent, to approach the state as a stranger is to foreground and make possible open and equal possibilities for everyone in dealing with the state, on the basis of citizenship as level ground (Olaniyan 2016).’

Some may immediately locate a problematic here, arguing that the state in Nigeria, as its police apparatus indicates, rather materialises itself to citizens through the crippling grip of domination and antinomies which make it a known foe that is untamable and must be accepted as a necessary evil. The fact that the state has failed to facilitate good governance and has been repressive led to its enemy status in the imagination of the average citizen. The state is then seen as a prized category to be cheated at every point possible because it is not a friend interested in citizens’ well-being.

Consistent with Olaniyan’s claim that ‘friends and enemies are on the same terrain of the known and decidable’, the police motto enacts the possibility of a state that can be known and knowable; it also demonstrates the ironic affirmation of friendship by state agents whose duty to protect and serve is eclipsed by the often tragic vexations it visits on citizens. People know the police is neither friend nor enemy, and they do not want it to be either of these.

Although the likelihood of Tejumola Olaniyan’s idea of the postcolonial state as a stranger that is potentially composed of the possibilities of friendship and enmity may be undesirable and undesired, equally important is the response of citizens who understand the state as an ambivalent mix of nearness and remoteness they cannot avoid. When we consider that friendship itself is shaped by the politics of vulnerability – understood not in its recent elastic articulations that foreground the condition of destigmatised victimhood but through the politicisation of injury and suffering, there is the sense in which the friendship the state and its agents offer subjectivises citizens as a vulnerable class endlessly susceptible to the workings of arbitrary power and brutality. To reject the identity of the vulnerable dictated by the state’s avowal of friendship is not to embrace enmity but the notion of the strange.

Even if those providing public service are not expected to be friends with citizens, they can at least be friendly. But the official response to #EndSARS showed might show this as illusory. The Police is Your Friend encroaches violently upon the public through barbaric police acts and culture from which proceeds limitations rendering life bare and disposable.

Giorgio Agamben’s notion of the bare life of homa sacer as sacred yet extinguishable through violent acts of politics does not overstate the present conditions of impunity that provoked #EndSARS. What Agamben calls the sovereign sphere, where ‘it is permitted to kill without committing homicide’, becomes operable as the very character of police brutality in Nigeria, a fact that galvanised youths and celebrities in a messy, leaderless but organised and organic protest both online and on the street. Nigerian Policing, as we find with the case of George Floyd and the Lekki killings, generates the condition for the operationalisation of sovereign power and its tragic exertions. In these avoidable killings in Nigeria, ‘the life caught in the sovereign ban is the life that is originarily sacred – that is, that may be killed but not sacrificed – and, in this sense, the production of bare life is the originary activity of sovereignty’. The Police is your Friend in this framework can be read as an empty signifier, a meaningless idiom that obfuscates the actual subjectivisation of life as bare and barren.

Thus, when Olaniyan writes that the ‘state ought not to be anybody’s enemy or friend, but a stranger – a stranger is structurally and substantively composed, in a chastening way, of the possibilities of both’, one wonders how this meaning of the state as a stranger comes across to people who have experienced real violence. In other words, precarious dealings and forced encounters with state agents often propel cynical relations that produce traumatic and numbing relations with the state. This is the core of the #EndSARS protest, and it is one that speaks to a larger culture of human devaluation in Nigeria.

To speak up against this larger oppressive culture is to see #EndSARS as symptomatic of a more troubling social malaise in the body politic. In any case, if the ‘modern’ Nigerian state relates overwhelmingly to its citizens as though they were adversaries, or a nuisance best subjected to abjection, as Wale Adebanwi and Ebenezer Obadare astutely remind us, then to imagine a police establishment that can be friendly or even befriended is a herculean task indeed. After the so-called institutional ‘friends’ of citizens have repeatedly and traically forced themselves on the rest of us, #EndSARS emerged as a radical moment of counter-hegemony during which many Nigerian youths saw real friendship in the faces of one another. It is for this reason that #EndSARS could be read as enacting the conditions that made possible a celebration of the political possibilities of social media friendship and its transformative potentials.

Photo by Tope. A Asokere on Unsplash