Recent research in Somalia challenges core assumptions about the role of the private sector and diaspora in governance and state-building in fragile contexts. LSE’s Duncan Green talks to Dr Claire Elder at the Centre for Public Authority and International Development about the impact of her work and the benefits of focussing on ‘new’ issues in policy spheres.

This post is part of a series on public authority evaluating the pathways to real-world impact of research at the LSE Centre for Public Authority and International Development.

Talking to Claire Elder about the impact of her CPAID work on Somalia raises a whole host of issues around how research can influence policy and practice:

- How the act of researching for a PhD can itself lay the groundwork for future influence

- How exploring a problem can have impact, even if you’re a bit hazy on solutions (which makes attribution even harder)

- The benefits of working on a ‘new’ issue

Claire’s research focuses on two overlapping issues: the role of the Somali diaspora in shaping the development of Somalia in recent years; and how the private sector fills in for and challenges the role of the state in contexts emerging from war. A current paper (forthcoming in African Affairs) looks at how contracting and procurement (a long and essential component of elite bargaining and conflict reconciliation) undermines the resurrection of a legitimate central authority.

All these issues are, to put it mildly, political hot potatoes.

Before embarking upon her PhD, Claire was a research analyst for the International Crisis Group. She did not know at the time the extent to which she would continue to rely on her knowledge of international organisations and connections to politicians, the aid sector, business leaders and prominent diaspora figures in shaping her research agenda and impact. She has recently been requested to advise on diaspora policy and private sector development.

Her recent work on the ‘politics’ of business-state relationships exposes some of the falsehoods of privatised governance, and her doctorate exposes critical problems with current thinking and practice about diaspora-centred development. As she argues:

‘Diaspora have become the de-facto allies of development since the 2000s. The ‘diaspora option’, implemented through technical assistance programmes supported by the International Organization for Migration (IOM), have contributed to the formation of a contested ‘diaspora state’. In the specific case of these programmes, many ended up involved in politics and resentment mounts due to inequality in access to opportunities.’

The return of the diaspora isn’t the magic bullet that many in the aid sector hoped for – diaspora returnees can be highly politicised, pursue their own interests and use their connections with the aid sector to siphon off resources to them and their friends. Power and politics don’t disappear just because someone is returning from a spell in Europe or the US.

Her research on technical assistance in 2017/18 had caused quite a stir amongst donors, ultimately bringing the issue to the Aid Coordination Unit, informing the decision of some donors to withdraw support for the programmes (as they reported directly to her). The World Bank also abandoned the diaspora component to its Capacity Injection Programme in 2019 until further review. She stayed in touch with the IOM, who came back in 2020 and asked her to become an expert adviser for an IOM working group that is drafting a new diaspora policy for the government.

The challenge of impact attribution

But, like many academics whose work seeks to influence policy, highlighting problems alone often makes it even harder to prove impact (‘attribution’). If you come up with a whizzy new solution – a new policy or an analytical ‘toolkit’ like the political marketplace – that is adopted by a government or aid agency, you can reasonably claim some of the credit. But if what you are saying is ‘look again, this is not what you think it is’ – it is harder to attach a specific outcome to your work. In other cases, impact can be unwanted if research is attributed but misconstrued.

Elder has done extensive research on business networks and business-state relations in Somalia, some of which has been funded by the World Bank. Her ethnographic PEA work that is concerned with policy agendas and structural problems within the ‘aid industrial complex’ can lead to some uncomfortable and unwelcome discussions about ‘tradeoffs’ and ‘power’:

‘Attributing impact in these cases can be frustrating business as you have little control over how your research will be interpreted (not least because hardly anyone outside academia reads the full paper). The report was widely circulated, top officials cited it was ‘eye-opening’, but the take-away from the World Bank group was to cut infrastructure investments not to rethink the underlying structures and violent hierarchies of profit, power and hegemony.’

In both cases, Elder has the benefit of producing cutting-edge research on relatively ‘new’ issues in development policy and practice. Private sector, like migration, is not new, clearly, but the aid sector has only recently become enthused with the transformative potential of both. A new issue that has less research attached is more likely to get picked up and influence critical debates.

And there is potential for knock-on in other countries; Elder is currently applying for larger grants to investigate how diaspora and the logistics economy is shaping conflict and ‘public authority’ in other contexts including Yemen, Libya, and South Sudan – all of which are (to some extent) emerging from conflict. She is likely to be in some demand for some years to come.

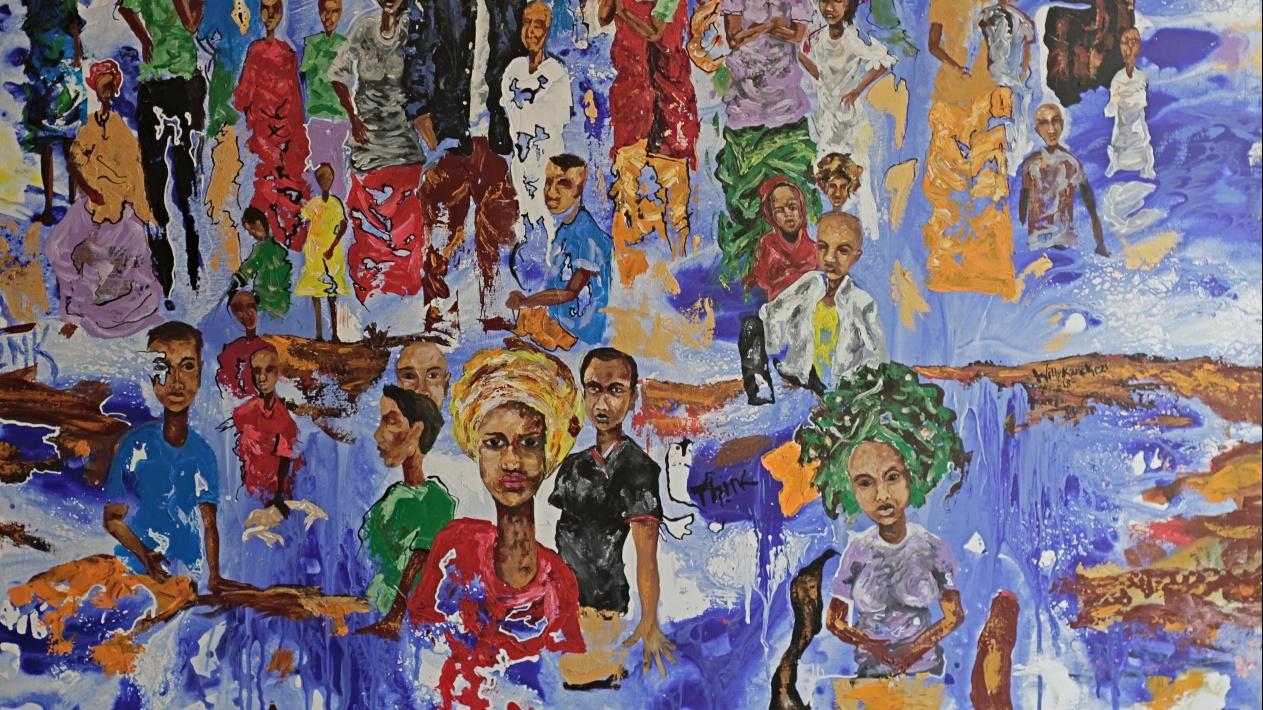

Photo: EUTM Somalia – Opening ceremony. EUTM Somalia. Credit: European External Action. Licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.