European migration bodies have supported the technological modernisation and militarisation of border posts in West Africa, interrupting long-term patterns of mobility in the region. An armed attack on a border post between Burkina Faso and Niger highlights the tensions these posts have caused, which speaks to broader European attitudes to livelihoods on the African continent.

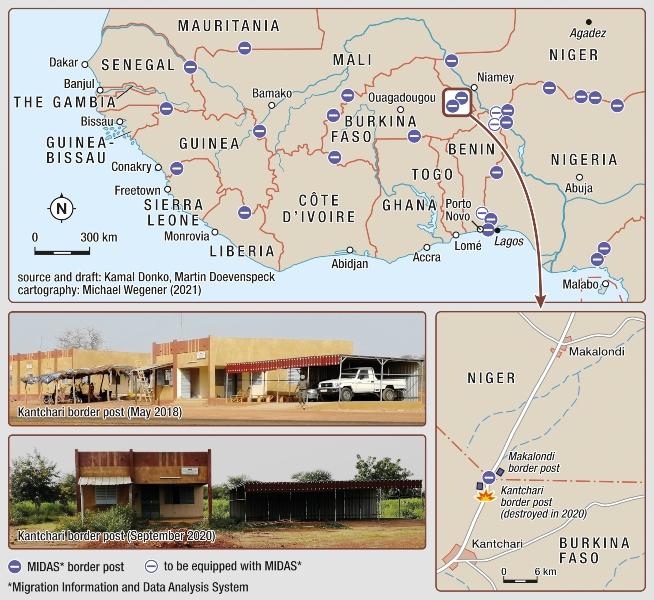

On 18 April 2020 non-identified armed men attacked and destroyed a border post just outside the town of Kantchari in the borderland between Burkina Faso and Niger. Merely two years before, in January 2018, this border post had been inaugurated. It was determined to be a place of strategic interest by the International Organization of Migration (IOM) and European migration control actors keen to extend the borders into the African continent and to stop West African ‘illegal’ labour migration as close to its origin as possible. International funders collaborating with the Burkinabè government not only established this brand-new border post building and site 18 kilometres outside of Kantchari, but also equipped it with state-of-the-art biometric border technology, including a fingerprinting system that is directly connected with a European database. The system would, for instance, block attempted re-entries after deportations early on. Furthermore, a number of newly trained border police officers were dispatched from the capital Ouagadougou and other regions in Burkina Faso, effectively replacing or reinforcing the local police force.

The externalisation of European ‘migration management’ to West Africa has thus resulted in technologically modernised and heavily militarised border posts and borderlands, threatening visa-free travel, freedom of settlement and borderland economies in the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). Migration control has interrupted historical mobility patterns, depleted the diversity of mobility practices and criminalised local economies. By taking the Kantchari-Makalondi borderland as a case study, our research examines the relations between border management, forced immobility, economic decline and violence.

Our research suggests the attack on the border post is a graphic result of this situation. The post was completely destroyed and everything that was not looted went up in flames, including the entire technological investment in migration control. The border post was already attacked on 4 April 2020 when one policeman was killed. As revenge, the army raided a village of Fula people nearby the border post. This in turn led to the attack and total destruction of the post on 18 April.

To this day, controls are therefore carried out at the former border post at the outskirts of the town, close to the customs and the Gendarmerie. As all the technical equipment went up in flames, too, there has been a return to old paper-based control practices, presumably with all the well-rehearsed practices of controlling and passing. While the newly trained reinforcement officers from the capital are still around, they are also based in the town of Kantchari and use the former paper-based systems. In addition, the security forces now also lack the basis for controlling the informal border crossings where they run an increased risk of being ambushed. As a result, non-documented border crossings have increased again.

On the one hand, this assault was both an attack on symbols of a contested state in general, and on a specific location of state intervention in the regional economy, which had heavily depended on the mobility of people and goods. On the other hand, the event and the dynamics of mutual attack and revenge should be understood in a broader context of the complex conflict situation. Looking at this situation from a relational analysis enables us to see that the border is not only made by the state and their agents, but also by surrounding actors, such as citizens winning and loosing from shifting border and mobility regimes.

This agency manifests both in a Kantchari that is now economically starved and in unemployed informal borderworkers. In its most extreme form it has resulted in a radically shifted border regime: namely a burnt down high-tech border post that underlines the significance of borders for understanding the multiple spatialities of violence and conflict.

One local policeman analysed the change Kantchari saw after the new border post and migration regime was implemented:

‘Between ourselves, I’m going to tell you a secret. Illegal trafficking was convenient for everyone and especially for us. With this new tool (MIDAS), we can no longer honour certain commitments. Before there was mutual understanding between the transporters and us, everything was going well. It was a win-win situation for both of us. But now everything has become complicated. Today people find themselves unemployed, the hatred against the state and its symbols is real. It is badly thought out by the decision-makers in our country who are in the pay of Westerners … I confess that this policy and the repression that followed has plunged everyone into poverty. One must always be afraid to stay next to the hungry, he will do anything to reach his objective’. (Informal conversation, Kantchari 18 December 2019)

Reading the border as a relational space enables us to grasp the multiplicity of effects changing migration policies. These effects do not only impact those who travel, but also affect the spaces they travel through, get stuck in or do not seek out anymore. However, if space is to be understood as a process of and result from relating objects, places and people, borders present an empirical challenge. For if people are stopped at borders, space can become a container for them. Refugees stuck at the European Union’s external border can attest to this. In addition, the closing and separating function of borders and the control and prevention of circulation puts at least two spaces, on either side of the border, in a specific relationship. With the spatial spread of control and barring functions, borders can thus be understood both as relational spaces themselves and, at the same time, relations of spaces. Carefully attending to the wider relational effects of a changing mobility regime enables us to see the border as constitutive of and embedded in the making of space.

Our research understands the violent borderland as being constituted in and through such multidirectional relations, relations between new and existing practices of border management, mobility control and struggles and resistances, relations between people, ideas and infrastructures. By having studied the processes by which ‘irregular migrants’, ‘human traffickers’ and violent actors are made through relational practices, we have shown that migration control is not a discrete, given entity. Carefully attending to the subaltern geopolitics of uneven practices and spaces of (im)mobility and resistance allows us to understand better how configuring European borders impacts African livelihoods and, indeed, how Africa and Africans are situated and valued in global geopolitics.

Learn more about work at the Bayreuth Cluster of Excellence ‘Africa Multiple’.

Photo: Flintlock 2018 Training in Agadez, Niger. Credit: U.S. Navy photo by MC3 (SW/AW) Evan Parker/Released. Licensed under CC BY 2.0.