Comparisons of British and French colonialism in Africa have typically examined the legacy of institutions but ignored colonial public investments in health and education. New research into these investments finds they are better predictors of today’s development in Francophone than Anglophone Africa. As conflict and political instability has been similar between these two sets of countries, Anglophone Africa’s higher economic growth in recent decades is suggested as eroding the persistence of colonial investments.

Comparisons between British and French colonialism in Africa, and their legacies, have long interested social scientists and historians. In Africa, most have compared and contrasted British and French institutions of colonial rule or have examined whether one set of institutions was better, or less bad, for political reform and economic development. By contrast, studies examining colonial investments and their legacies on African development are scarce if we exclude the literature on missionaries, a largely private investment in education.

The focus on institutions alone is unfortunate because public investments in sectors such as health and education reveal a government’s preferences for resource allocation, especially when formal institutions (laws and rules) are unclear, as was the case in most of British and French Africa. Further, colonial-era investments, and not just institutions, are important to understand current development, with recent research showing that districts with higher levels of investments then are more developed now, as proxied by literacy, nightlight density and other development proxies.

Colonial investments as development predictors

In a recently published article, I use district-level data on public investments in former French West Africa (henceforth Francophone Africa for simplicity, even if the French empire extended beyond West Africa) and in former British East and West Africa (henceforth Anglophone Africa) to examine two questions.

Are colonial investments equally good predictors of today’s economic development in both former empires? Colonial institutions in French colonies were more homogeneous and investments were less unequally distributed across a colony’s districts than in British colonies. This could be seen as facilitating interregional redistribution after independence and, with it, a reduction of the colonial-era footprint when compared to Anglophone countries, some of which became deeply divided between directly and indirectly ruled areas (such as in Nigeria, Sierra Leone and Uganda).

However, I find that investments in health and education are better predictors of today’s level of development in Francophone than in Anglophone districts. That is true if we exclude East Africa and thus restrict the comparison to West Africa.

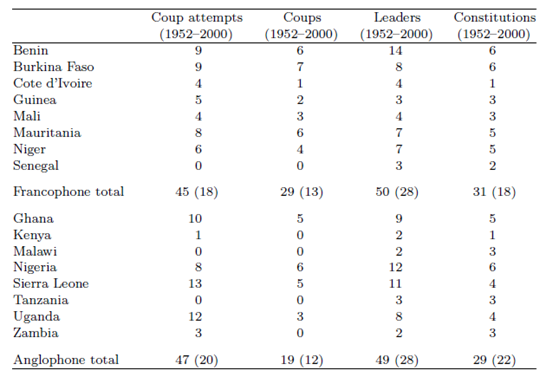

Why is the historical persistence of these investments lower in Anglophone districts? I first thought that conflict might explain the difference. The basic idea here is that if Anglophone countries suffered from more conflict after independence, their higher political instability should reduce persistence, for instance by increasing the rate of government turnover and thus the changing of distributive preferences. I collected data on measures of political instability, such as coup attempts, coups, leadership turnover and the number of constitutions since independence. As Table 1 shows, however, Anglophone countries have not suffered from more instability than Francophone countries.

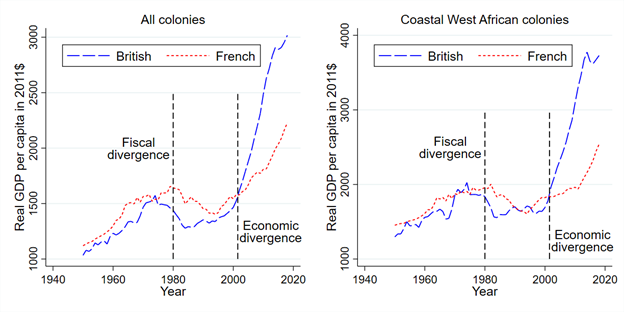

Given that levels of instability are not the source of the difference, I consider the impact of economic growth in recent decades. Analogously, higher levels of economic growth between the colonial period and today might erode the persistence of colonial-era investments. I find several empirical patterns consistent with this idea. First, this only makes sense if growth has actually been higher in Anglophone than in Francophone countries. Figure 1 show this to be the case. While growth levels in sub-Saharan African have been overall low by world standards, they have been higher in former British colonies since 2000. The origin of this divergence in growth may date back to 1980, when Anglophone countries increased their fiscal capacity.

The second pattern concerns investments per capita. Public investments were higher in French West Africa than in British colonies on a per capita basis. However, nightlight density, educational achievement and access to health care are now higher in Anglophone countries.

Third, colonial investments in Anglophone Africa were (even) more unequally distributed across districts than in Francophone Africa, but this may no longer be the case. Regional inequality in East and West African countries remains high (such as between the centre and the periphery, urban and rural areas, the coast and the interior), but Anglophone countries may have closed the colonial-era gap.

Fourth, I find that colonial investments are less predictive of current development in districts of countries with higher growth records. This again suggests that growth and changes in economic activity erode the persistence of colonial investments.

Remaining questions

To the best of my knowledge, this is the first academic paper examining why colonial investments predict current levels of development in Francophone Africa more so than in Anglophone Africa. It is certainly not the last word on the topic. Future research could try to geolocate economic activity more precisely and investigate how changes in the location of economic activity erode the persistence of investments and inequality, for instance, if activity increases more in poorer regions.

Finally, the two mechanisms examined here to understand differential persistence (conflict and economic growth) do not preclude other explanations. The article’s goal is more modest: to encourage researchers and policymakers to further understand differential legacies of colonial investments and, in doing so, formulate policies that may foster development and reduce the regional inequalities that East and West Africa inherited from colonial rule.

Read the full article in the Journal of Historical Political Economy.

Photo: Healthcare worker provides vaccination. Credit: Erick Kaglan / World Bank licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.