The link is often made between “good governance” and the ability to meet long-term development goals. But what is good governance, exactly? A new report suggests that good governance that promotes transparency of policy in Uganda can improve economic performance and achieve human-development SDG targets.

Good governance has been touted for its positive impact on sustainable development. Estimating and understanding how changing governance can improve other development outcomes quantitatively is therefore a critical lens through which sustainable development can be viewed. However, the term “governance” is often a difficult concept to pin down, and its measurement is a complex exercise. Terms like accountability, transparency, inclusiveness, responsiveness and rule of law all form part of the criteria in assessing what constitutes good governance, but how should policymakers assess the effectiveness of their governance frameworks?

A USAID commissioned study by the Pardee Center analyses the progress of development in Uganda since 2015 and evaluates various policy choices and their impact. The report uses the International Futures (IFs) forecasting model to design alternative scenarios and potential improvements to Uganda’s development trajectory. It outlines the challenges faced and the opportunities that Uganda could leverage in its efforts to promote human development and achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Among the various sectoral scenarios investigated, good and quality governance is identified as a vital component in amplifying development efforts in the country.

Uganda’s good governance trajectory

The government of Uganda has long recognised the many ways governance has a role in the pursuit of sustainable development and has made considerable efforts, particularly since 2007, to promote good governance in aspects of its political, social and economic life. This has resulted in proactive needs-based planning mechanisms at both the national and local government level.

Due to these efforts, Uganda has made a marked improvement in governance in the last decade and, according to the 2020 Ibrahim Index of African Governance (IIAG), the country ranked 22nd (out of 54 countries) with a score of 51.8 (out of 100 points), three points above the African average. The index takes an integrated approach to measuring governance under four categories: security and rule of law, participation rights and inclusion, foundations for economic opportunity and human development. Uganda’s progress has largely been a slow improvement, although a decline in the overall index was observed between 2018 and 2019. The largest deterioration was observed in the security and rule of law and participation rights and inclusion sub-sectors. Meanwhile, the overall African trend shows that improvements in good governance have had a profoundly positive effect on human development and foundations for economic opportunities.

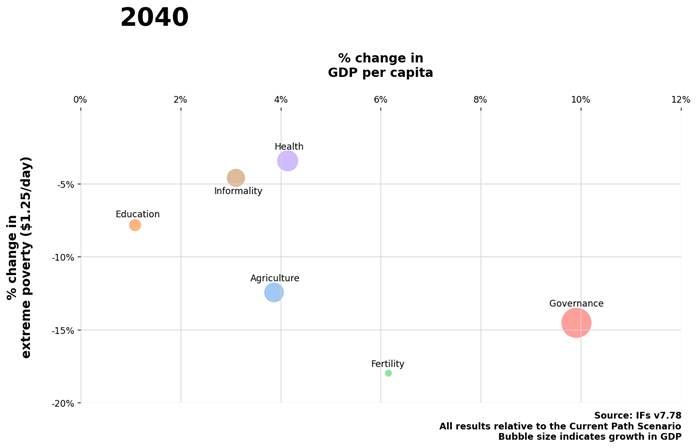

The cyclic and compounding benefits of quality governance can also be observed in Uganda. The results of the study indicate that improved governance has the broadest benefits among other competing priorities and results in the largest increase in economic growth and income. The Improved Governance scenario modelled in our report places a particular emphasis on the importance of transparency in light of Uganda’s oil prospects and the potential benefits accrued to Ugandans if transparent management of the resource can be achieved. In this instance, the scenario simulates a future in which corruption is reduced and Uganda achieves improved transparency.

In the Improved Governance scenario, the rate of corruption is reduced by 40% over a five-year period from 2023. As a result, gross domestic product (GDP) and government revenue gradually increase and, by 2040, are more than 10% over the Current Path modelled for that year. The proceeds of a much larger GDP and government revenue, if well managed, can help the government of Uganda to extend a range of public services and goods like water, sanitation, electricity, health and other basic infrastructure. In turn, these improvements could lead to greater gains on key human development indicators that underpin the SDG goals.

Because of higher economic growth expected in this scenario, extreme poverty, for example, is projected to fall from about 40% in 2021 to 13.5% in 2040, compared to about 16% in the Current Path, representing approximately 1.7 million fewer people living in extreme poverty in that year. Although Uganda still does not achieve the headline SDG goal to eliminate extreme poverty even by 2040, it shows that greater effort to improve all aspects of governance beyond corruption could increase productivity and reduce, by significant margins, the timelines currently projected for Uganda to meet the SDG targets.

Decentralised solutions as alternative pathways

Another report by the Pardee Center reiterates the need for good governance and explores alternative pathways that could be prioritised or pursued simultaneously, recognising that many developing countries will likely not meet many SDG goals. The report advocates for Decentralized Solutions, an approach that promotes a more organic mix of development efforts, such as strengthening local governance and rural development, promoting local energy production and sustainable agricultural practices, among others.

Uganda has already taken considerable steps to institutionalise this form of governance through the creation of local government authorities, a management framework for its natural resources, such as oil, and integrated climate-smart systems in its agricultural policies with the help of non-government organisations (NGOs), private sector and civil society.

However, the implementation of such a system comes with synergies, trade-offs and challenges for Uganda. Mobilisation of both domestic and external revenue is one of the biggest constraints to an effective decentralised governance system. To mitigate some of these challenges, Uganda could capitalise on its oil resources through greater transparency to avoid the pitfalls of the “resource curse”, while making concerted investments to improve efficiency of other sectors in its economy such as agriculture.

In addition, targeted external assistance, strengthening local government capacity and better coordination with the national government could promote effective good governance. Such an integrated governance plan could put Uganda a step closer to achieving many of the human-development related SDG goals alongside these efforts. Importantly, if Uganda is to gain greater traction towards the SDG targets, there needs to be a shared commitment to stability and growth upheld by the principles of transparency, inclusive decision-making and informed policy choices.

Photo credit: Michell Zappa. Licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.