Africa is facing many development challenges. This has inspired policymakers and scholars to advocate for African governments to use military personnel and apparatus in development projects, a phenomenon known as ‘African developmental militarism’. But, as O.A. K’Akumu writes, having the military in the civilian space may lead to conflicts of interest.

Advocates of African development argue that the military is often the best-equipped institution in many African countries. It has highly trained personnel, known for their discipline and efficiency. In contrast to the disciplined forces, the private and public sectors of many states are perceived to be corrupt, inefficient and driven by special interests.

Colonel Birame Diop of Senegalese Air Force, when seconded as the Director of the African Institute for Security Sector Transformation wrote: ‘In certain countries such as South Sudan and Zimbabwe, the situation in the public and private sectors is so delicate that for several years to come, the military will remain the only functioning organisation capable of dealing with certain national challenges.’

In 1998, Johanna Mendelson Forman and Claude Welch, writing for the Centre for Democracy and Governance, said: “The reality is that the armed institutions of these developing states often form one of the few nationwide institutions that is present outside the capital city. But beyond the mere physical presence of soldiers, militaries have frequently acted as the main tools of the state to deliver such services as health care, infrastructure repair, and even educational services.” Forman and Welch made this observation decades ago yet very little appears to have changed.

The threat of mission creep

Allowing a powerful institution into the public realm could result in it dominating the space and hampering the growth of public and private sector actors in the national economy. This is against prevalent ideologies that prioritise the development of these sectors. For example, the New Public Management paradigm seeks to enhance the capacity of public sector actors, while neoliberalism promotes the interests of the private sector actors.

Across Africa, militaries have a practical history of development work. The Ethiopian Herald wrote in 2017, “Army has been participating in various development activities including the construction of major roads, building schools and health posts in collaboration with and high participation of local community in a manner to respond to natural disasters and fight against poverty’’.

But many groups argue that drawing the military into the civilian space leads to the militarisation of African societies and will inevitably politicise the institution. Political elites may take advantage of such indulgence to use the military for national problems that require political solutions. Once they start doing the work, military leaders may also want to influence the political decisions with the worst-case scenario being a total takeover of government through a coup d’état.

Uganda is a classic case of this phenomenon. In 1966 the Parliament of Uganda demanded that then Prime Minister Milton Obote be investigated following allegations of corruption. This was an internal political problem that Obote decided to solve by using the military. Obote moved against Uganda Parliament by revoking the existing constitution that made Kabaka Mutesa II the ceremonial President and declared himself President of Uganda and promoted Idi Amin Dada to the position of Commander in Chief of the armed forces. Amin’s forces then drove Kabaka into exile. This left Obote as both head of state and government. Amin later deposed Obote through a coup d’état in 1971.

This playbook has been seen in different parts of the continent. Egyptians have lived under developmental militarism for the last seven decades, following the 1952 coup d’état by Gamal Abdel Nasser. Egyptian society is the most militarised in Africa and the army is involved in different facets of the economy from kitchenware to food production.

In early 2020, the Kenyatta government moved to take over Nairobi’s municipal service provision from a democratically elected local government. This began when the central government brought up criminal charges hinged on allegations of corruption against the city’s elected Governor Mr Gideon Kioko Mbuvi. The functions of the local government were taken over and given to a newly created Nairobi Metropolitan Services (NMS). The president then proceeded to appoint military officers to head and manage NMS. In doing this, the president relied on the virtues of the military as an efficient and non-corrupt institution. Nonetheless, the move generated intense politics of developmental militarism in the capital city. It was opposed by politicians, specifically, members of the legislature and the Governor of Nairobi. President Kenyatta’s move was a case of using the military as a shortcut solution. He had accused the Governor as the head of local government of being corrupt but there were political means of solving such a problem other than drawing the military into the civilian duties of a sub-national government including traffic decongestion, provision of water, and the construction of hospitals.

The logic of developmental militarism can be used to depose the leader of a local government. However, the politics of pro-involvement and anti-involvement remains the same even if played in a democratic context. As a political debate, whatever the pros and cons, African developmental militarism is here to stay.

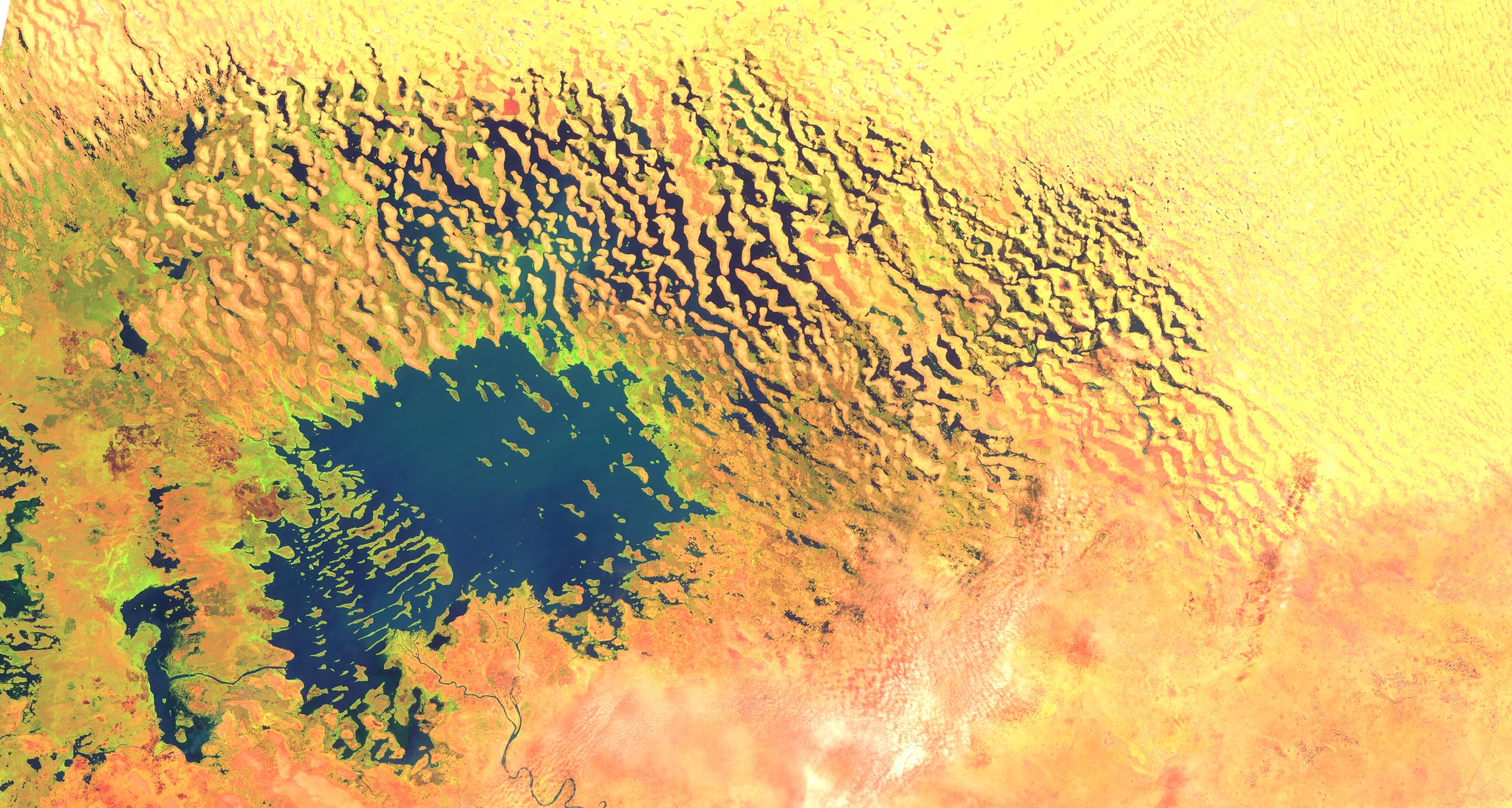

Photo credit: Defence Imagery used with permission CC BY-NC-ND 2.0