The European Union’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism wasn’t designed to hurt African exports, yet it could end up affecting them more than those from elsewhere in the world. Given Africa’s low contribution to global carbon emissions, Jamie MacLeod asks how CBAM fits into the agreed principle of ‘common but differentiated responsibilities’.

Countries around the world are designing increasingly creative policies – involving both carrots and sticks – to try to steer their economies towards reducing carbon emissions. Some, like the US, are emphasising the carrots with programmes like the (poorly named) Inflation Reduction Act which involves $369 billion in tax credits and subsidies to promote domestic green industries, such as electric vehicles. The EU, on the other hand, went for sticks. It first implemented an Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) that has, since 2005, gradually ramped up the price of emitting carbon for certain industries using a “cap-and-trade” approach. The next cab off the policy rank: CBAM.

Carbon border adjustment measures, like the EU’s CBAM, ostensibly seek to address one of the weaknesses of an ETS. Namely, companies can circumvent higher carbon prices by relocating abroad where carbon isn’t taxed. From there they can export into the EU market without reducing emissions and with less overheads because they have avoided additional carbon charges. The process has been dubbed ‘carbon leakage’.

CBAM will require importers to buy certificates to cover the difference between the carbon price that is paid in the country of production and the price of carbon in the EU ETS. The carbon price on imports will be based on the weekly average auction price of EU ETS and applied to emissions declared by importers.

In many countries, particularly lesser developed ones without well-developed carbon monitoring and reporting systems, that won’t always be possible. In those cases, the charges will be set at the average emissions intensity of the 5 per cent worst-performing EU installations.

The measure will initially apply to goods deemed to be at high risk of carbon leakage including iron and steel, cement, aluminium, fertiliser, hydrogen and electricity. It will be applied to all countries with certain exceptions for ones with closely aligned carbon market systems.

CBAM will begin with a transitional period, involving reporting but no charges, from October 2023. In January 2026 full implementation will begin and by 2030 the list of covered products will expand.

Africa and the EU

The EU is Africa’s most important export market, so African countries are particularly sensitive to EU trade policies. Around 26 per cent of Africa’s fertiliser exports are destined for the EU, although exports of Africa’s iron and steel (16 per cent), aluminium (12 per cent), and cement (12 per cent) are less exposed. If CBAM is extended to cover manufacturing, fuels, or agricultural goods, Africa’s exports would be even more affected with almost a third of each current sent to Europe.

Many producers in African countries are not yet using the cleanest and greenest technologies, which would require capital and intellectual investment. Electricity supplies on the continent are instead often reliant on older, cheaper, and less green sources. For example, South Africa is the most industrialised economy on the continent and still sources around 90 per cent of its electricity from coal. As a result, production in African countries is often more carbon intensive than competitors elsewhere in the world. Any CBAM tariff will therefore be proportionately higher for African countries, putting them at a competitive disadvantage.

Effect on Africa

At €87/tonne, the average ETS price of carbon in 2022, CBAM would increase tariffs on Africa’s exports to the EU by 6.3 per cent for fertiliser, 11.3 per cent for iron & steel, 8.5 per cent for aluminium, and 13.5 per cent for cement. These additional tariffs would be higher than those levied on countries including India and China, in some instances by a factor of two because of the greater carbon intensity of production in Africa.

African exports to the EU of the covered products would fall because of the tariffs and reduce the GDP of African countries by up to 0.9 per cent, which equates to about £20 billion annually.

While not insurmountable, these economic consequences are deceptively important. Africa’s industrial exports create formal jobs, raise substantial tax and foreign exchange revenues, and contribute to a pathway for meaningful economic development through industrialisation.

Some countries will be affected more than others, and in certain sectors, it will be substantial. The worst hit will include Mozambique, Gabon, Libya, and Mauritania, because of the importance of EU exports to their economies. South Africa’s metals sector, which is important for jobs but is already struggling due to persistent energy crises, will also be affected.

How do African policymakers feel about CBAM?

For many African policymakers, the EU’s CBAM is unfair, particularly in light of the ‘common but differentiated responsibilities’ principle established in UN climate negotiations. They are aware that African countries are responsible for just 2.8 per cent of historical carbon emissions, and that the average fridge in the US consumes about three times as much electricity as the average Kenyan or Nigerian.

As Kevin Urama, the Chief Economist of the African Development Bank, said at the African Economic Conference in December 2022, “It’s hard for Africans to put closing coal plants first when a fifth of our population remains undernourished”.

No one would argue that African countries should remain poor. The challenge is to ensure economic growth while transiting to cleaner energy and production methods. One should not be sacrificed on the mantle the other. That requires care in the design and implementation of carbon measures by the leading economies of the world.

Impact and equitability

The world needs policies like the EU’s CBAM to urgently cut carbon emissions. But it needs these measures to be designed with fairness in mind so that the poorest don’t shoulder an unequal burden and are instead supported to grow and develop. When trade and climate experts in the EU designed their CBAM, they probably had climate at the front of their minds, and perhaps competitive pressures with countries like China or the US second. Unfortunately, the effects on Africa and many of the world’s least developed countries appear to have been overlooked.

Production processes and energy generation in African countries need investments and finance to become greener. That will involve partners like the EU following through with climate finance commitments, but also efforts to promote access to greener technologies (potentially in a similar vein to the Covid-19 vaccine patent waiver). Countries will need new and additional assistance to set up carbon monitoring and reporting systems so this doesn’t become another non-tariff barrier to EU market access. A graduated implementation of the CBAM for less developed countries would be welcomed, to give them longer time frames to adopt improved production methods and adjust to reporting requirements.

The EU’s CBAM is so important because it sets a precedent. With the UK, Japan, Canada and potentially the US investigating similar policies, the EU’s CBAM will establish the benchmark that others will follow. It’s worth making sure it works for everyone.

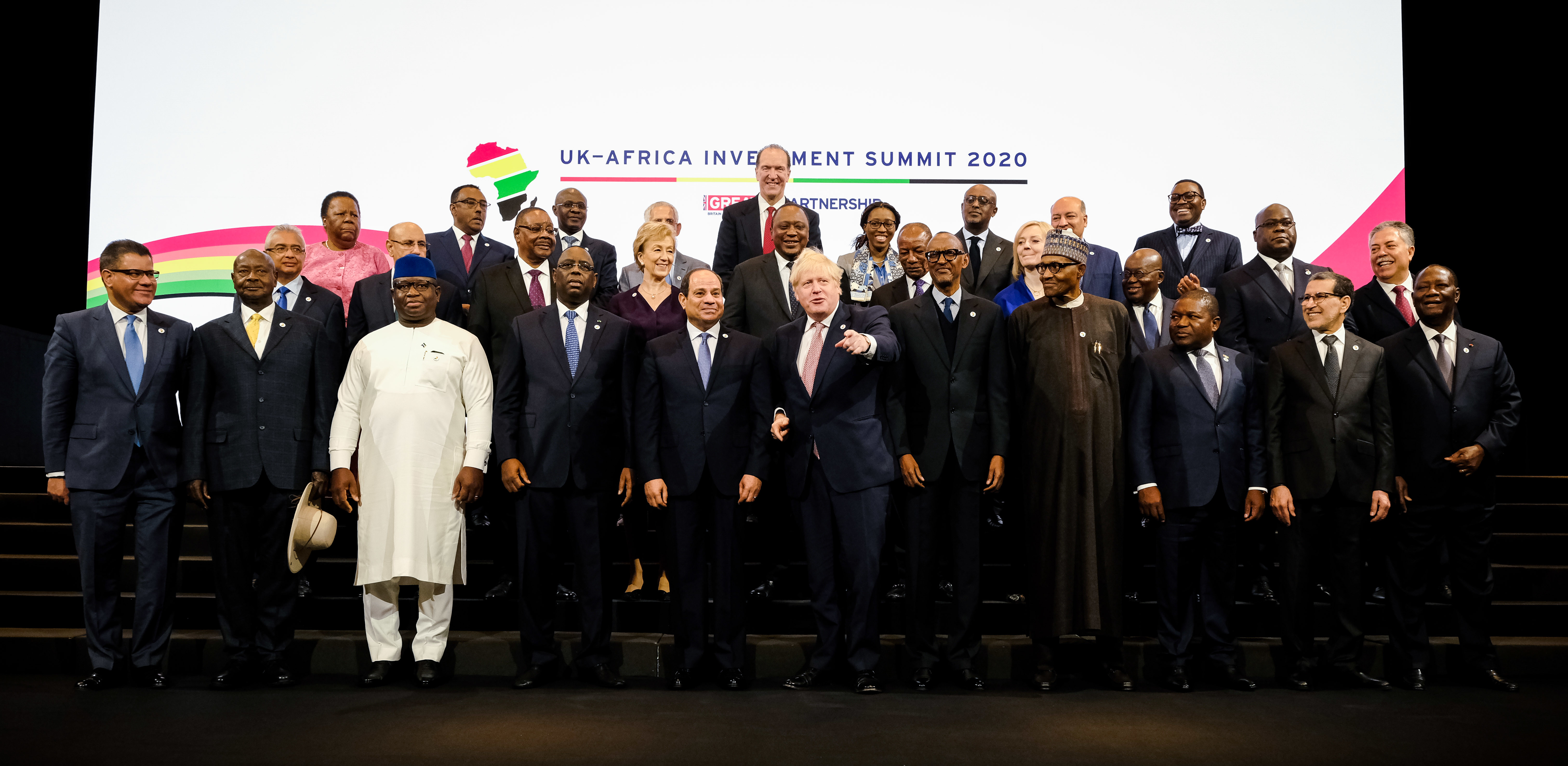

Photo credit: Carsten ten Brink used with permission CC BY-NC-ND 2.0