China’s economic activities in Africa have expanded rapidly over the last two decades and now cover trade, investment, infrastructure, construction, manufacturing, and development finance. Unlike the European Union, which has long had an explicit trade policy structure, or the US’s Africa Growth and Opportunity Act, China only has a basic policy framework in place for facilitating trade and investment flows between itself and African countries, writes Kulani McCartan-Demie.

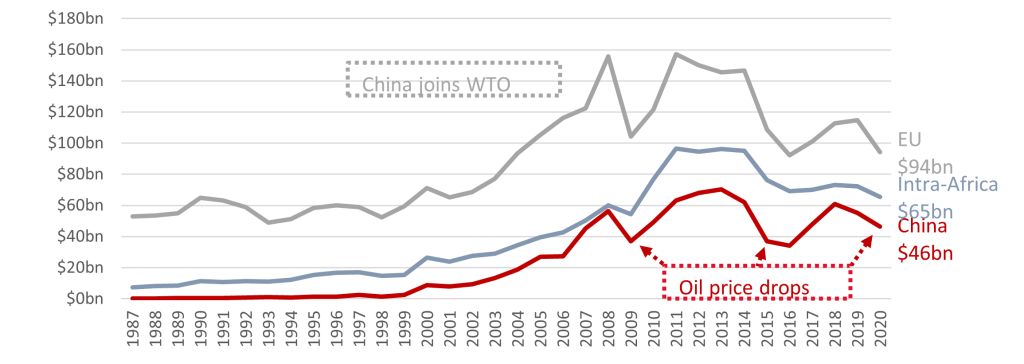

The relationship between China and Africa could perhaps best be described as ‘casual’ and ‘open’, even as African countries are committed to expanding their trade opportunities with China. The rapid trade growth has seen China become Africa’s second most important trade partner after the EU (Figure 1). While this ‘friends with benefits’ arrangement may be newer, China has become a preferred partner for African countries looking to master the delicate two-step dance of trade and industry. China offers investments to scale industrial development through manufacturing to produce goods, and a huge potential market to trade goods and services.

After three decades of 走出去战略 “Go Out” policy encouraging Chinese investments overseas and the acquisition of foreign technology and know-how, China appears to have changed track. While this period saw an expansion of global export markets and trade surpluses, many overseas investments were unsuccessful. In 2020, Chinese President Xi Jinping adopted a “Dual Circulation” strategy, pledging to reduce overseas capital outflows and rebalance growth towards domestic consumption. The new approach translates into reduced development financial flows, with a £16.1 billion reduction announced at the 8th Forum for China-Africa Cooperation, and preceded by a sharp plunge in global lending by China’s largest policy banks, China Exim Bank, and the China Development Bank.

The reduction of financing is not exclusive to Africa, nor does it indicate a deteriorating relationship with China. Instead, the dual circulation strategy aims to deepen and intensify private sector investment with targeted support to smaller and medium-scale projects as opposed to large-scale infrastructure deals. It is unclear how this will impact the ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), but as China restructures its financial engagement, its relationship with Africa appears to be maturing from the hot flush of speed dating into a steady courtship. Whether this is truly a ‘partnership of equals’, both sides have entered a new stage in their economic relationship.

Casual but unbalanced

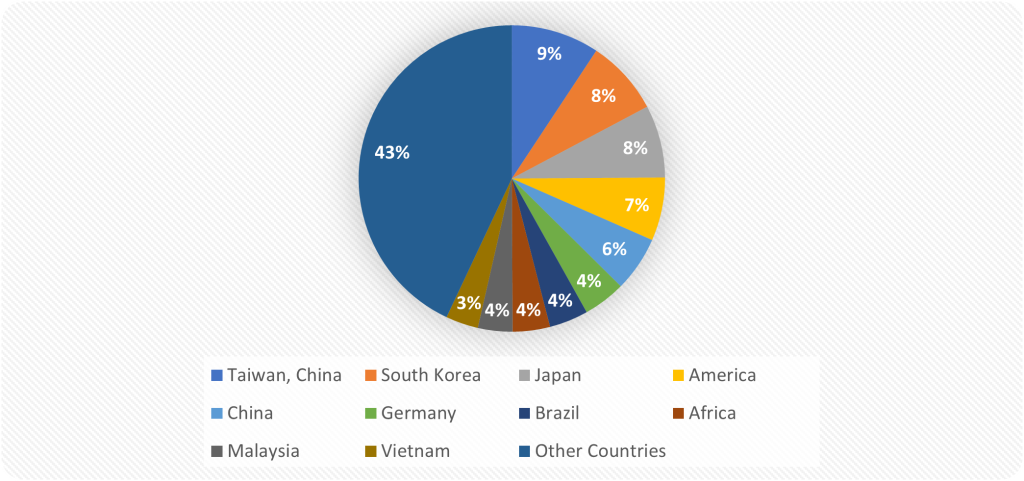

Africa’s trade with China is unbalanced. It is typically made up of low value-added commodities being sent to China and manufactured goods being sent back. The volume of China’s trade with Asian countries (£2.47 trillion) is far greater than that of African countries. Africa’s share of China’s £4.84 trillion global trade in 2021 was only 4 per cent.

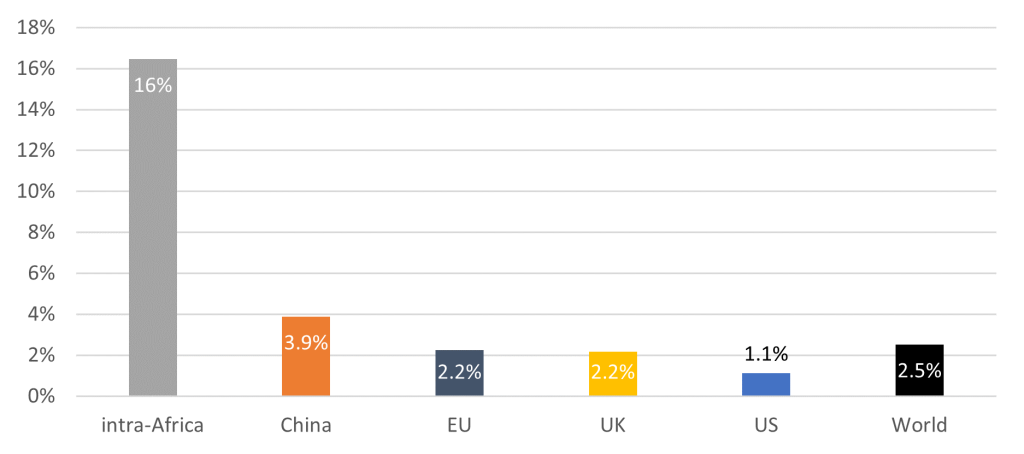

While the volume of trade is comparatively low, the value of Africa-China trade has grown substantially but unevenly (accounting for commodity shocks). Africa’s exports to China have grown from £56.4 billion in 2013 to £84.6 billion in 2021. This growth in value is not the result of a diversified African export basket and Africa continues to run a trade deficit with China.

The bulk of China’s imports from the continent continue to come from a handful of resource rich African countries and through a relatively undiversified export basket compared to Africa’s exports to the rest of the world. China satisfies its appetite for commodities through imports from across the world – not just Africa. Yet, during its speed-dating with various African economies, Chinese finance emerged as a large force for natural resource-rich countries such as Angola and Nigeria, reflecting its relationship priorities in Africa: access to vital natural resources including platinum, iron ore, copper, cobalt, timber, and petroleum for Chinese industry.

Trade policy interests and arrangements

African countries are generally in the initial stages of designing a China trade policy. Only the most basic framework is in place for trade engagement between Africa and China. Of the three major arrangements, the first is the obligatory World Trade Organisation most favoured nation privileges that cover all WTO members. Second, the concessional arrangements for the least developed countries through China’s duty-free quota-free initiative covering 33 African countries. Third, a free trade area agreement that was signed in 2021 between China and Mauritius.

African trade policy is focused on the following areas: trade promotion, access to technology know-how, emerging e-commerce initiatives, clarifying sanitary and phytosanitary regulations, and “green lane” schemes to fast-track inspection and quarantine processes for African produce. China’s trade interests concentrate on natural resource imports from Africa and export of manufactures.

Chinese financing for infrastructure along with investment in manufacturing has also driven this “open relationship”, which other partners are now trying to emulate. Though, this dating pool appears to be tilted in favour of China; forty-four African countries signed up to the BRI.

Make it official

As the world’s second-largest economy, China remains an important trade partner for Africa. Yet, China’s current trade offer to Africa falls below expectations. While there is increasing uptake by African LDC eligible for China’s duty and quota free market access, China does not offer a generalised system of preferences. A preferential programme like that offered by the US’s AGOA should also be a key priority, especially given the fierce competition from Asian countries which have better market access arrangements with China.

China should rethink its engagement model with Africa. The Forum on China–Africa Cooperation offers an opportunity for collective diplomacy, but it does not provide an institutional framework for transparent monitoring of its outcomes. The trade promotion target to boost non-oil exports from Africa to £241.77 billion by 2024 also needs to be accompanied by investments in the industrial capabilities of African firms to produce value-added goods and the reduction of tariff and non-tariff barriers that currently inhibit market access.

African countries need to coordinate to design a coherent trade policy with China to overcome the bottlenecks for exports. African policymakers need to align a fully formulated industrial policy to the emerging investments in the manufacturing landscape from China. Production in China’s Economic and Trade Cooperation Zones (ETCZs) in several African countries should be aimed not only at global exports but also at the continent-wide market that is being created under the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), providing a major boost to exports and intra-African supply and value chains. Policymakers have more agency to set their relationship boundaries with China, and while “keeping it casual” through informal bilateral arrangements may have taken precedent up until now, it’s time for trade policy engagement to ramp up a notch and “make things official”.

This blog draws on research from How Africa Trades published by LSE Press.

Photo credit: GovernmentZA used with permission CC BY-ND 2.0