Are UK civil servants at the centre of EU bargaining – at the “top table” – or are they on the periphery? Simon Hix is Harold Laski Professor of Political Science at the LSE and Senior Fellow on the ESRC’s UK in a Changing Europe programme.

Are UK civil servants at the centre of EU bargaining – at the “top table” – or are they on the periphery? Simon Hix is Harold Laski Professor of Political Science at the LSE and Senior Fellow on the ESRC’s UK in a Changing Europe programme.

The data for this analysis come from 869 interviews by Daniel Naurin, at the University of Gothenburg, and his research team between 2006 and 2012.(1) Daniel and his researchers asked a simple question to each member state’s official in the same 11 committees and working groups in the EU Council: “Which member states do you most often co-operate with in order to develop a common position?”. The answers reveal which governments tend to work together in EU negotiations, and as a result which governments are better connected than others. Also, as the research was conducted in 2006, 2009 and 2012, it is possible to look at whether there have been any major changes since the Eurozone crisis and the growing Brexit debate.

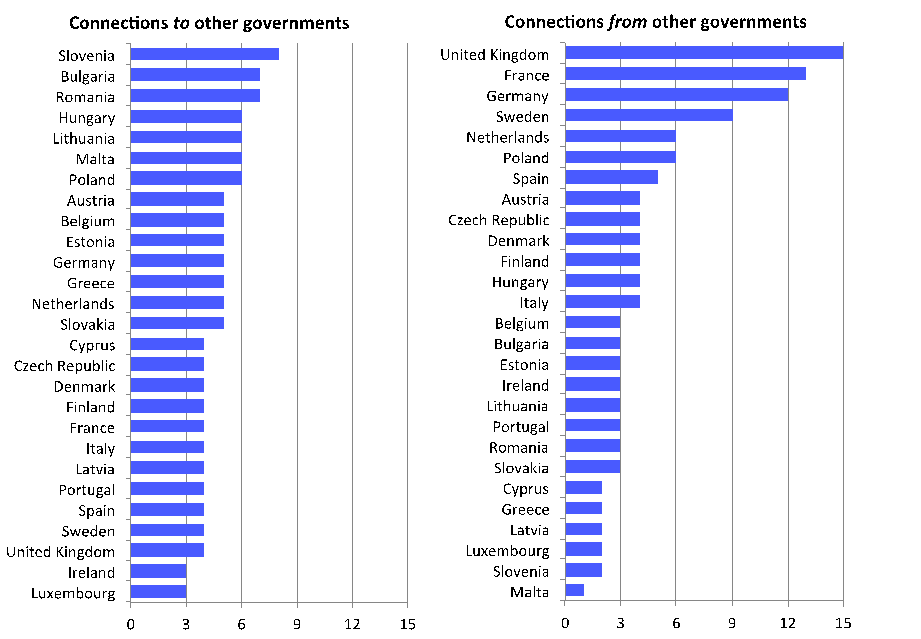

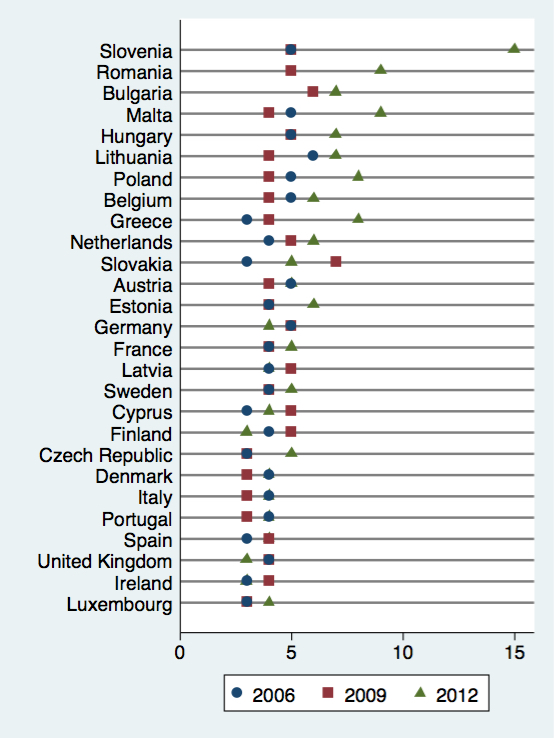

To start with, Figure 1 shows the two side of the connections: (1) how many other governments each government said that they worked with (were connected to) on average in each year; and (2) how many other governments mentioned a particular government (were connected from). Put together, these two measures give an indication of how much influence an EU member state’s officials have in EU negotiations.

Figure 1. Connections in EU Council negotiations

So, UK officials on average mentioned 4 other governments they co-operated with: France, Ireland, Netherlands and Sweden in 2006; Germany, France, Ireland and Sweden in 2009; and Germany, Netherlands and Sweden in 2012. As the figure on the left shows, the officials of most other member states mentioned a higher number of other governments with which they co-operate. This might reflect the fact that the UK officials feel confident that they can achieve their aims without needing the support of many others. For example, the officials from the other large member states (Germany, France, Italy and Spain), with the exception of Poland, also mentioned only a small number of other governments, whereas the officials of many of the smaller member states named a higher number.

The centrality of the UK, along with the other large member states, is clearly revealed in the number of officials from other EU governments who mentioned the UK (in the figure on the right). Measured this way round, the UK’s officials are the most well connected of all the governments. In fact, the officials of only 6 other governments (out of 26 others) did not mention the UK as the main government they co-operated with in their working group in either 2006, 2009 or 2012: Greece, Italy, Luxembourg, Portugal, Cyprus, and Romania. Not surprisingly, France and Germany, as the other two most powerful member states, were the second and third most mentioned by officials from other governments. Interestingly, though, amongst some of the smaller member states, several of the UK’s traditional allies (Sweden, the Netherlands, and Denmark) are also central players in EU negotiations.

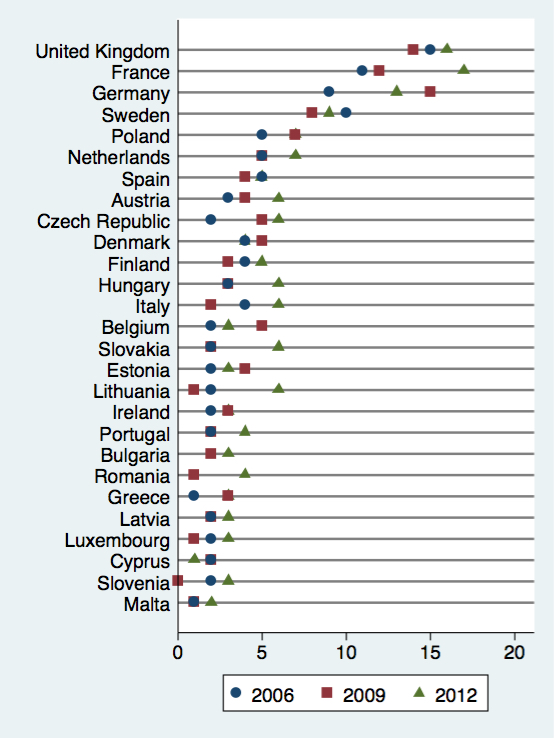

Figure 2a (above). Changes in connections over time: connections to other governments

Figure 2b. Changes in connections over time: connections from other governments

Figure 2 shows the breakdowns for 2006, 2009 and 2012 separately. The UK’s position has been stable across this period, both in terms of connections from other governments to the UK (on the right) as well as UK connections to other governments (on the left). If anything, the number of governments connecting to UK officials increased between 2006 and 2012. Overall, the main change between 2006 and 2012 has been the increase in the number of connections made by officials from some of the newer member states (such as Slovenia, Romania, Malta and Poland) to governments from the other member states. In short, not much has changed (yet) in day-to-day EU negotiations since the eurozone crisis.

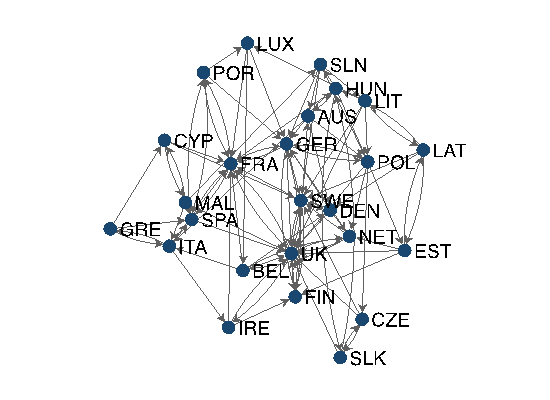

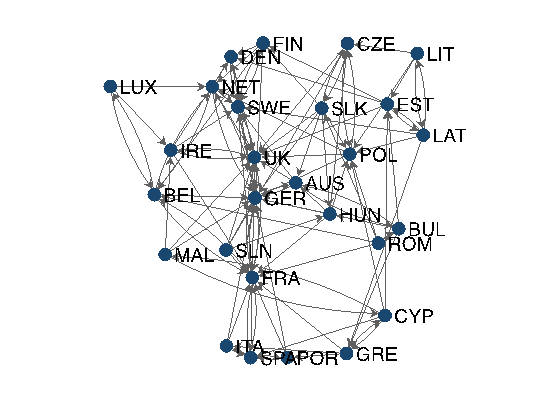

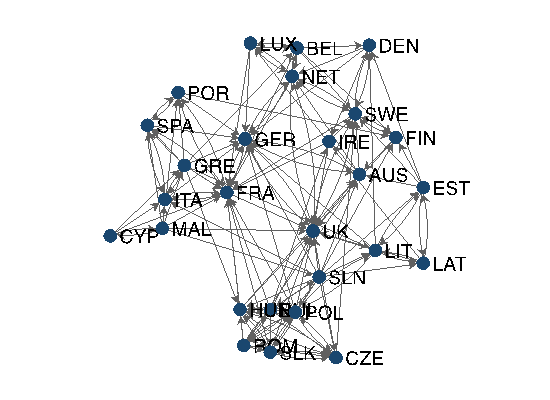

Finally, whereas these numbers reveal how many connections each government has, they do not show which groups of governments work together. To illustrate this, Figure 3 shows the network of connections in 2006, 2009 and 2012. In these figures, the arrows show the direction of a connection from one government to another, and the positions of the governments are determined by how many connections each government has as well as who they are connection to: with the more connected governments closer to the centre, and governments with similar connection patterns located closer together.

Figure 3. EU negotiation networks

2006

2009

2012

These network pictures clearly show the centrality of the UK in EU negotiations. Germany and France are also close to the centre, but UK officials appear to be the best connected of all the member states’ officials.

In other words, when it comes to negotiations behind the scenes, before votes take place and before laws are adopted, the data suggest that the UK government is right at the heart of EU policy-making, and certainly at the top table, alongside Germany and France. The data also suggest that the eurozone crisis has not had any noticeable effect on the centrality of the UK in EU bargaining.

As ever, though, there are some caveats. I have only focussed on the “first” other member state each official mentioned (although looking at the second, third and fourth mentioned member states does not affect the conclusions). I have also not looked into connections in particular policy areas, and the UK clearly cares about some policy areas more than others. And, for a full picture of the UK’s position in EU politics, these findings need be considered along other results.

Endnote

(1) See, for example, Daniel Naurin and Rutger Lindahl (2010) “Out in the cold? Flexible integration and the political status of Euro opt-outs”, European Union Politics 11(4) 485-509.

This article represents the views of the author and not those of the BrexitVote blog or the LSE.