What impact would leaving the EU have on Britain’s higher education and research? The second hearing of the LSE European Institute’s Commission on the Future of Britain in Europe took place on 8 December. Convenor Anne Corbett reports on the discussion.

What impact would leaving the EU have on Britain’s higher education and research? The second hearing of the LSE European Institute’s Commission on the Future of Britain in Europe took place on 8 December. Convenor Anne Corbett reports on the discussion.

Situation, challenge

Higher education and research do not have a place in David Cameron’s shopping basket of EU renegotiation items. But they are an obvious topic for a higher education institution such as the LSE to take up at a defining moment in Britain’s relationship with Europe. The sectors directly or indirectly affect millions of lives, and by extension, the economy and society.

What is more, there are a few surprises about the EU policy scene in higher education and research. Out of the limelight of European Council and leaders’ summits, these are domains where the trend of the last decade has been to closer and almost uncontested European integration – linked to the European Research Area managed by the EU, and to the European Higher Education Area as a platform for best practice and capacity building, which is managed by the intergovernmental Bologna Process and supported by the European Commission.

A recent study backs the idea that the higher education arena might also be politically salient. Students are currently tantalising the political campaigners by saying that on the one hand they are instinctively pro-EU and, on the other, that they have yet to think as to how or even whether to vote.

At the time the LSE Commission hearing took place, Universities UK (UUK), the collective voice of the universities, and Scientists for EU, a widely supported grassroots movement, had already campaigned for several months on the grounds that a Brexit would be a catastrophe for British research and innovation.

Universities for Europe, the UUK campaign group, gives five reasons for voting ‘Remain’:

-

The EU supports British universities to pursue cutting-edge research leading to discoveries and inventions which improve people’s lives

-

It supports British universities to grow businesses and create jobs

-

It makes it easier for UK universities to attract talented students and staff who contribute significantly to university teaching and research and benefit the UK economy

-

The EU helps universities to provide more life-changing opportunities for British students and staff

-

It provides vital funding to the UK’s most talented researchers, supporting their work in areas from disaster prevention to curing cancer.

Source: Universities for Europe

The Scientists for EU case is summed up in their evidence to the House of Lords: the UK does extremely well out of its EU connections and there is realistically no alternative game in sight.

This group sees a causal link between the UK’s global success and membership of the EU. The European community of science has critical mass. It is the most productive hub of science worldwide, bigger even than the US. The UK should understand that there is a virtuous circle linking UK achievements and the EU’s strong scientific standing.

The Brexit campaigns argue that Britain would be better off outside the EU. The polls suggest that the messages ‘Vote Leave, take control’ and ‘Vote Leave, go global’ have significant public appeal. This perspective formed part of the discussion in the hearing, although it was only afterwards that the leading Brexit campaign, Vote Leave, published its full argument on research and innovation sector.

As convenor of the hearing, it is my view that the two and half hours of debate were constructively framed and promisingly modified. The key question was whether or not the weight of evidence supports the view that the EU enriches what the UK can do. The points put forward by the participants – academics, academic leaders, the policy community, the student voice and more – suggested that it was not enough to think in economic terms of ‘added value’. The core issues for higher education and research were not only the headline-grabbing questions of funding and control. In a global and technologically connected world, what ultimately matters for higher education and research are how best to secure benign conditions for the production of knowledge, and how to enhance the student experience. The interest of the hearing was how the experts balanced these factors.

The EU’s importance to higher education and research

Conditions for the production of knowledge

The idea that a Brexit would be a catastrophe for research and higher education was challenged in this hearing. There would be many ways for Britain to get what it wanted if it left the EU, said some participants. The UK government would have money available once Britain’s contribution to the EU ceased. It could make up for the loss of EU funding by financing research and industrial innovation through what Britain recovered for public funds by now longer paying into the EU budget. It could buy back into EU programmes like non-EU member states, Norway and Switzerland. There would be new incentives to develop and enhance bilateral and ‘Anglosphere’ collaboration, especially with the US , Canada and Australia. In any event a Brexit would not lead to sudden change or all ties being lost. Britain’s global reputation would give it favourable terms with its ex-partners in the EU, and new opportunities for international collaboration bilaterally and with the ‘Anglosphere’.

Participants at the hearing with hands-on experience of major collaborative projects contested all these points. Major disruption would follow and much would be lost. The UK has contributed hugely to the fact that the EU has now acquired global critical mass in research. Why lose its place at the table? Even the Anglosphere argument looked shaky on examination. Australian innovation strategy, for example, prioritises links with China.

These experts drew in their own experience in research and innovation collaborations to cite the effectiveness of the EU as a hub. Big science and innovation projects, such as in the life sciences projects of the Knowledge and Innovation Centres (KICS) are geared at creating systemic change, not mere incremental improvement. To carry out such work they need a pool of resources, data, and infrastructure that are beyond the capacity of a single state.

But such projects also flourish through shared bonds of knowledge and ideas. The UK has got into the habit of working closely with its European partners. The scientist-led European Research Council has succeeded in attracting excellent researchers from all over the world to work in Europe, and many of them come to the UK. The Horizon 2020 programme has proved effective in identifying challenges common to member states. It is win-win, according to these experts. The UK contributes massively in expertise. But UK research efforts have also been strengthened by the EU, both in terms of particular projects and by exploiting the EU’s global reach as a stepping stone to research collaborations world-wide.

Higher education – trade or education

Global trends that make higher education, like research, increasingly international and collaborative, drew out the different perceptions of the experts present. For the UK government and the policy-making world, higher education is widely perceived as a tradeable service where the UK performs strongly. Hence again the argument that the UK’s excellent global reputation and the drawing power of its universities would enable the UK to go it alone and escape from EU bureaucracy.

There would be no risk of UK campuses becoming insular should a Brexit happen: UK students get international experience at home. UK universities could recruit more international students. The government would lose less taxpayers’ money on EU students attending English universities who then disappear without repaying their loans. It would not bear the costs of the Erasmus programme. Brexit could make for better targeted collaboration with chosen bilateral relationships, the provision of scholarships for selected EU students, and an incentive to develop the ‘Anglosphere’ in which the UK is so much at ease.

But for many participants the EU’s relevance to higher education was broader-based. For young people their higher education experience comes at a time their personal and professional identities are being forged. The global context is crucial. This is true of lifelong learners too.

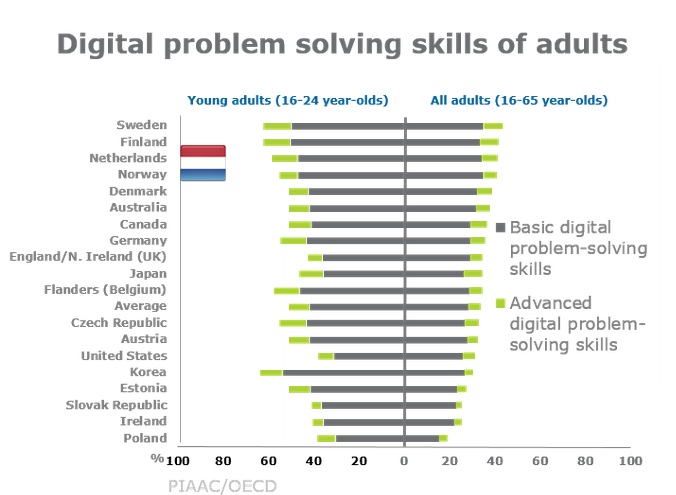

No one connected with the higher education world should ignore the recently published OECD report Education at a Glance, whose striking graphic was presented at the hearing:

Employment prospects for those without the high level problem-solving skills that higher education is intended to deliver have suffered badly in the last decade: middle-rankers have not progressed, the prospects for those with low problem-solving skills have stayed stable while those with middle range problem-solving skills have plunged. Higher education itself cannot ignore the message that employability more than ever depends on a mix of knowledge and skills, ranging from the technical to the personal.

Not only does that mean more (and diverse) higher education and more individual international mobility. The EU-backed schemes for mobility and study abroad have a contribution to make, through cross-border sharing of educational experience and skills through students and academics. These have spin-offs into higher education’s wider cultural and democratic function. The decades-old Erasmus programme has long proved its worth and in the case of the UK, the hearing confirmed that the presence of Erasmus students brings a welcome European dimension to student life and to teaching. The latest incarnation, the Erasmus+ programme, has a much expanded sectoral coverage and more international reach. These are success stories, and some sort of alternative to the more apocalyptic headlines in the press on the state of the EU.

The EU has also been pragmatic in its approach to the higher education domain. It is limited by treaty to do no more than offer support for quality-building efforts – other than where EU fundamental law impinges. That has some downsides. Some social scientists are currently up in arms against a recent directive on data sharing, which they say inhibits longitudinal studies.

But much of the work of the European Commission directorate concerned, Education and Culture, is to network institutions and even individuals to share what is regarded as best practice for a modernising, globalising agenda. While new opportunities for Commission activism have arisen as higher education and research have become central to the EU’s growth strategy Europe 2020, it is a vital support for the intergovernmental Bologna Process – and the European Higher Education Area, in which 48 countries now participate.

One outcome presented at the hearing is that the Bologna Process has generated practices and standards taken up in other areas of the world. An example is quality assurance regulation. QA also shows – in microcosm – signs that the possibility of the UK voting to leave the EU has already precipitated some loss of influence at European level. The British, pioneers in this area, have just been dropped from the decision-making body.

To sum up: expert opinion remains divided as to whether a Brexit would lead to catastrophe, to opportunity, or to a middle way ‘of course we’ll muddle through’. But two findings might enrich a wider debate. This hearing brought to the fore that there is much more at stake in these policy sectors than funding and control. A lot of research and higher education practice happens within a collaborative European frame. There is a rational justification in all this for making the most effective use of the attributes of a university: its knowledge, its talent and its ideas.

Nor should we underestimate how personal involving these issues are for thousands of potential voters. Students themselves may be stepping up to the plate. An academic in European studies reports that her students actively demand to be informed about both sides of the argument. But there are reports the pro-EU line has become so entrenched in higher education that those who disagree are treated as ‘pariahs’. Why can’t we be advocates, asked another academic at an impassioned moment of the hearing . We have given our professional lives to the cause of European integration.

‘I don’t want to be insular,’ said the student representative present, reacting to the idea that such cornerstones of the EU as freedom of movement and non-discrimination between EU citizens might be imperiled. It echoed the sentiment of a submission to the hearing: ‘The political has become personal, very personal’. There are surely lessons here for all the political campaigns.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the BrexitVote blog, nor the LSE.

Dr Anne Corbett is an Associate at LSE Enterprise. She was convenor of the hearing on Research and Higher Education, LSE Commission on the Future of Britain in Europe, and is the author of ‘Universities and the Europe of Knowledge: Ideas Institutions and Policy Entrepreneurship in European Union Higher Education Policy, 1955-2005 (Palgrave 2005).

How wonderful a thing it is that the ever generous EU give so much money to UK universities.

How magnificent that the EU gives us a teeny weeny bit of our own money back while keeping Billions of our money for their lovely projects & keeping the 55,000 EU civil servants in the sumptuous lifestyle they are accustomed to.

Wunderbar.