President Obama’s intervention into the debate over whether or not the UK should leave the European Union has been attacked by Eurosceptics in the UK. Tim Oliver writes that given that the UK and US frequently interfere in one another’s domestic matters, and the concerns in Washington over the consequences of Brexit for both the EU and the transatlantic relationship, Obama is justified in openly stating his opposition.

President Obama’s intervention into the debate over whether or not the UK should leave the European Union has been attacked by Eurosceptics in the UK. Tim Oliver writes that given that the UK and US frequently interfere in one another’s domestic matters, and the concerns in Washington over the consequences of Brexit for both the EU and the transatlantic relationship, Obama is justified in openly stating his opposition.

Anybody following the news will not have failed to notice that President Obama’s visit to the UK and his views on Brexit, along with a host of other such comments including a letter to the Times by eight former US treasury secretaries, have drawn the ire of Eurosceptics in the UK. While a lot of this criticism has consisted of nothing more than puerile abuse, the chief complaint voiced in this context has been that the President is unduly interfering in what should be a strictly domestic matter for the UK.

There is a degree of hypocrisy here given some of those who have criticised Obama think nothing of calling on him and the United States to intervene in other problems around the world. Nor have many of those on the political right, in particular, held back from calling on the US to push the UK and other European allies to spend more on defence. As was made clear recently in his interview with The Atlantic, Obama has previously had to push David Cameron on the issue of UK defence spending. As is always the way with an American President, Obama is damned if he does say something and damned if he doesn’t.

It is also little more than a fantasy to believe that the US does not already interfere in UK domestic matters and vice versa. Indeed, this occurs on a daily basis in the relations between any set of advanced democracies in the modern world. It is particularly true of those states on either side of the North Atlantic: while the world has been mesmerised by the achievements of emerging markets such as China and India, it has overlooked the extent to which Europe and North America have become economically interdependent, and the extent to which developments on one side of the Atlantic can have implications for regulatory matters and security cooperation on the other side.

Brexit cannot therefore be seen as a purely domestic matter. Yes, it is a choice the British people alone will make, but the consequences are not for them alone. Voting to leave the EU would be a decision that would transform the UK, change the EU and reshape the transatlantic relationship. It would have clear economic, political and security implications for the US and several other countries. These are not issues any US President – be they Republican or Democrat – could stay silent on. And as the leader of the Atlantic alliance, the American position matters not only for the British people, but for the rest of Europe as well.

The American view and the wider consequences of Brexit

President Obama is not speaking out against Brexit simply as a favour to David Cameron. The President has tried – if not always successfully – to adopt an approach to international relations which avoids unnecessary conflicts, and he is wary of pursing a rigid doctrine that could result in reckless decisions. He has previously summed this philosophy up quite simply as ‘don’t do stupid shit.’ And in a rather crude way that is precisely how he, and Britain’s allies, view Brexit.

The United States is not alone in making clear its opposition to Brexit. No government of a country allied to the UK – countries who have in the past gone as far as to fight wars with Britain – has supported the idea of the UK leaving the EU. Britain’s closest neighbour, the Irish Republic, has repeatedly warned that the economic and security implications for it and Northern Ireland mean it strongly opposes a Brexit.

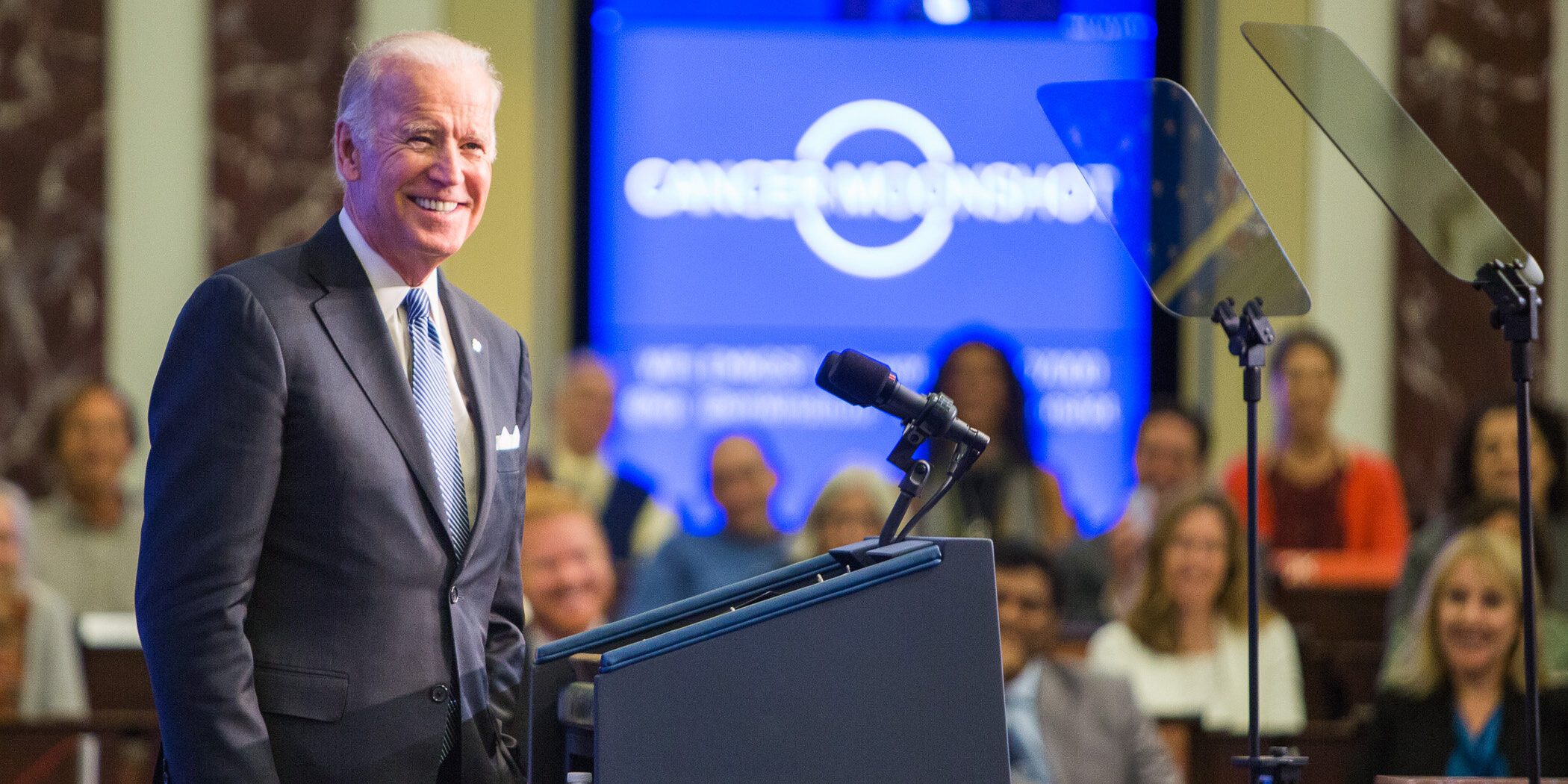

Credit: The White House

Surveys of European allies and countries around the world, such as one run in 2014 by the DGAP, reveal deep worries about where a Brexit would take the UK, as well as concerns over what Brexit may mean for their relations with the UK and the mutual interests and relationships they have in common. A Brexit would also clearly change the EU. It would lose one of its largest, most outward looking and important member states.

The EU today reflects a list of British successes, such as the single market and the multiple enlargements that British governments supported. Brexit could shift the political balance in the EU, running the risk of making it less open, less interested in global issues, and less Atlanticist. Britain’s Brexit debate often overlooks how fragile the NATO alliance is or how Britain can also appear to free-ride on the United States’ security guarantee. The assumption among some Eurosceptics that it has been NATO that has kept the peace in Europe is as selective a reading of history as those who claim it has all been down to the EU.

For the US, the transatlantic relationship is not just about the so called ‘special relationship’. Accusations that the UK is a US ‘Trojan Horse’ inside the EU display an ignorance of the hand the United States has had in European integration from the very start and it is misleading to suggest that America depends on the UK for relations with the rest of the EU.

The closeness of Europe and the United States means the US is not going to give up on the EU even if Britain leaves. The US government wants the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership to work, not a smaller free trade deal with just the UK. A Brexit would mean Britain risks becoming an awkward ‘inbetweener’, beholden more than ever before to the ebb and flow of the wider transatlantic relationship.

Then there is the UK itself. The possibility of Brexit leading to economic damage to the UK, of instability in Northern Ireland, of heightening tensions between a global London and the UK, and finally opening the Pandora’s Box of Scottish independence means Britain’s allies and friends are understandably concerned about where a Brexit would leave one of their closest allies.

And let us not forget that once the British people have had their say, the rest of the EU and Britain’s allies will have theirs. If Britain votes to leave, then it cannot simply demand a new relationship with the EU of its own choosing. That new relationship will be one the rest of the EU – including the European Parliament – will have to agree to and they will have their own red-lines. The suggestion that the UK could join NAFTA as an alternative conveniently overlooks what the US may feel about this, let alone Mexico or Canada.

When all is said and done, a central part of the debate leading up to the EU referendum will be hearing the opinions of countries such as the United States and Britain’s other closest allies and friends in the world. Without these views being heard, the debate will be one that is oblivious to how much Britain’s place in the world – like that of any other modern state – depends on the behaviour and outlook of others. As such, we should welcome President Obama’s intervention as a development that raises the public’s understanding about the potential consequences of Brexit.

This article first appeared on the UK in a Changing Europe blog.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of BrexitVote, nor of the London School of Economics.

Tim Oliver is a Dahrendorf Postdoctoral Fellow on Europe-North American relations at LSE IDEAS and a Non-Resident Fellow at the SAIS Center for Transatlantic Relations. He has also worked at RAND, the Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst, LSE, UCL, the House of Lords and the European Parliament.

In the long run both Obama and Cameron will turn out to be right on this.