Some of the recent reactions to the Article 50 judgment in the High Court are frankly frightening. Gavin Phillipson asks whether rightwing politicians and journalists attach any value at all to what we call ‘the rule of law’ or ‘the independence of the judiciary’? He worries that they are out simply to bully the judges and whip up hatred against them. In this post, he elaborates on the Brexit vote’s implications for the relationship between politicians and the rule of law.

Some of the recent reactions to the Article 50 judgment in the High Court are frankly frightening. Gavin Phillipson asks whether rightwing politicians and journalists attach any value at all to what we call ‘the rule of law’ or ‘the independence of the judiciary’? He worries that they are out simply to bully the judges and whip up hatred against them. In this post, he elaborates on the Brexit vote’s implications for the relationship between politicians and the rule of law.

David Davis, the backbench MP for Monmouth (not the Minister for Brexit) complained of ‘unelected judges calling the shots – this is precisely why we voted out!’ Jack Lopresti MP said ‘unelected judges should not seek to thwart the will of the British people’, while Suzanne Evans, candidate to be the new leader of UKIP, called for the judges who gave the judgment to be sacked – a tweet she at least had the grace to delete. Meanwhile Douglas Carswell, supposedly the moderate voice of UKIP, suggested the judgment showed the need to get some different judges by reforming judicial appointments, while MPs and journalists ‘furiously’ accused ‘activist judges’ of mounting a ‘power grab’, seeking to overturn the referendum result.

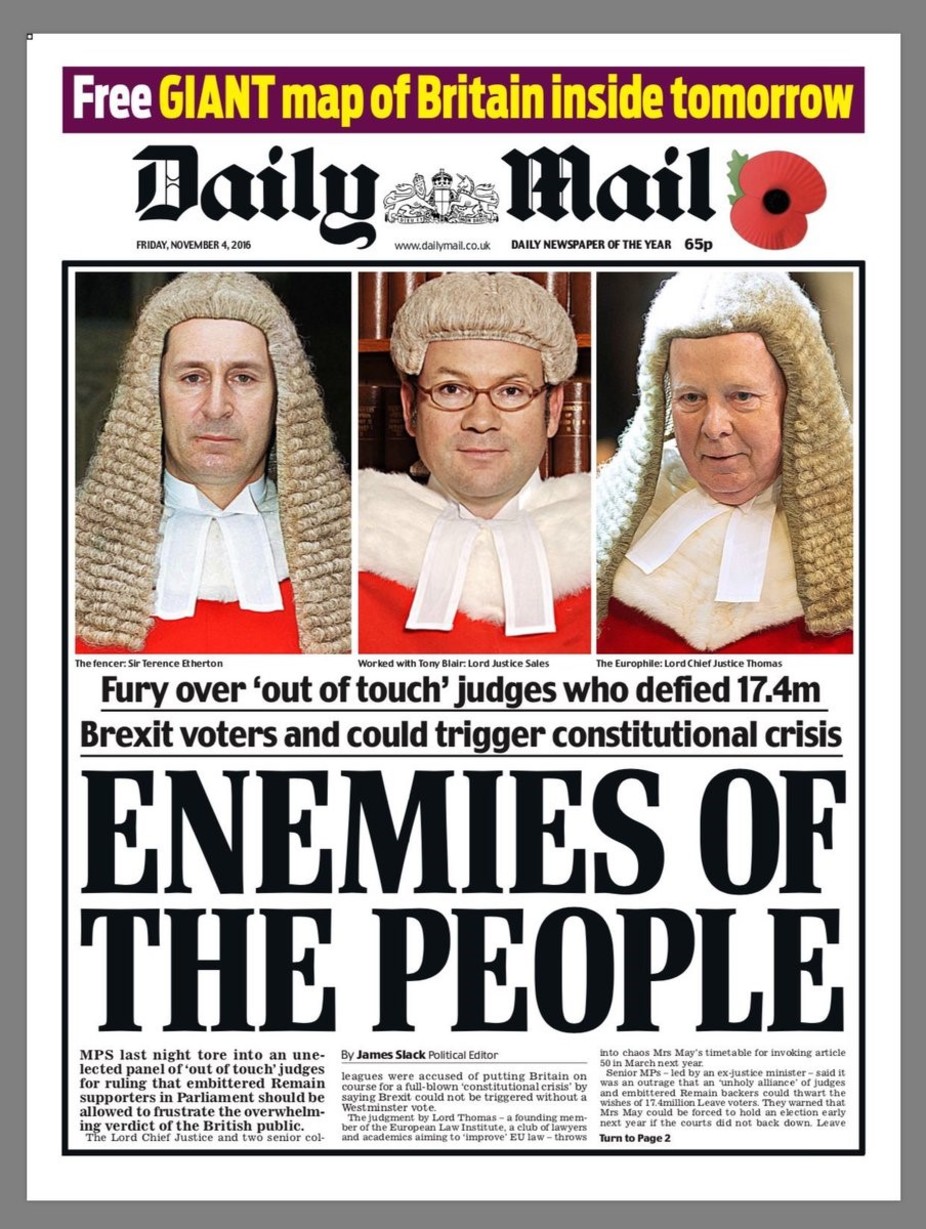

This seemed bad enough but then came the blaring headline in the Daily Mail, over a picture of the three High Court judges: ‘ENEMIES OF THE PEOPLE’. The paper talked of the ‘fury over ‘out of touch’ judges who defied 17.4 million Brexit voters’. The Express, even more hysterically, shrieked that the judgement left Britain in ‘’a crisis as grave as any our country has faced since the dark days when Churchill vowed we would fight them on the beaches…’ Not only was all this laughable or dangerous nonsense, but it seemed to betray the most basic misunderstanding of our most fundamental constitutional principles – as well as of the judgment itself, which it seemed no-one felt any obligation to actually read before wading in to attack it.

Rule of law

First, there seemed to be a widespread assumption that courts just decide cases like politicians – to get the policy outcome they personally favour. Hardly anyone seemed to accept that decisions like this are simply the courts’ best assessment of what the law requires. But read the case yourself: it’s an elegant and powerful, but purely legal argument. As the judges say at the beginning of the case:

It is agreed on all sides that this is a [legal] question which it is for the courts to decide…Nothing we say has any bearing on the question of the merits or demerits of a withdrawal by the UK from the EU or on government policy.

That legal question was one of the most basic the courts must decide in any state in which the government, like the people, is subject to law: does the government have the legal power to do want it wants to – in this case, trigger the formal Article 50 process of withdrawing from the EU? The court decided, unanimously, that the government lacked this legal power, because it is a bedrock principle of the constitution that the prerogative cannot be used to take away rights granted to citizens by Parliament – and that is precisely what triggering Article 50 would do. So this was nothing whatsoever to do with trying to stop the UK leaving the EU: it was making a purely legal finding about whether it is Parliament or the Government that can lawfully implement the decision to leave.

The sovereignty of Parliament

More broadly, what the court was doing here was upholding two fundamental pillars of the ‘unwritten’ British constitution – the rule of law and parliamentary sovereignty. The latter means the government can’t use the ancient, residual prerogative powers it inherited from the Crown to take away rights parliament has put into law – or render nugatory an Act of Parliament. In making this finding, the High Court was at pains to trace the subordination of the Royal Prerogative to Parliament all the way back to the great 17th century historical struggles between King and Parliament that resulted in the Civil War and the Glorious Revolution. That revolution was crowned by the 1689 Bill of Rights, which states, in words that were quoted and applied by the High Court yesterday:

The pretended Power of Suspending of Laws by Regall Authority without Consent of Parlyament is illegall.

Put simply: the royal prerogative can’t be used to take away your legal rights. What could be more wonderfully English than that? A high principle of liberty-under-law, ringing down through the ages from the 17th century! It’s a judgment that should have made any patriotic Brexiteer proud. And yet we got the reaction above. Do any of these politicians really disagree with having independent courts to decide when the government is acting unlawfully? Or think that politicians should be able to sack judges when they rule against the government, or pick ‘tame’ judges who never will? Do the newspapers want to incite hatred against our judges? Are they trying simply to intimidate them?

We can only judge what we saw – naked attacks on the rule of law and the independence of the judiciary and the grossest distortions of what the court actually decided.

This article was first published on The Conversation and it gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Brexit blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Photo by The Conversation: (CC BY 2.0).

Professor Gavin Phillipson is Director of the Human Rights Centre at the Durham Law School.

It is ironic that the whole point of Brexit was supposed to be to establish the primacy of Parliament and of our judiciary.

The revolution devours its children.

Having read the judgement in full I must agree that the High Court decision has clear legal merit. However, there is one very troubling issue that flows from the judgement. The Court declared that the Referendum was “Advisory”. Thirty-six million people cast their vote having been told by the government that the result of the referendum would be binding on the government. No one who voted did so in the belief that the result could be overturned by Parliament. This judgement now raises the spectre of conflict between the People and their Parliament. Whilst it is unlikely that Parliament will vote to block the Invocation of Article 50, there is every probability that Parliament will seek to limit the authority of the government to negotiate withdrawl from the EU so as to achieve all the freedoms that the people voted for.

So, I repeat, the High Court judgement is clearly correct in law. But, to declare, after the fact, that the referendum result was advisory when 36 million people voted in the rationally held belief that it was deterministic, is simply unnacceptable. This case should never have been heard. The question as to whether the case was justiciable in the national interest should have been tested independently before the High Court heard the arguements. Changing the rules after the game has started always creates ill feeling and mistrust.

Dear Nigel,

I knew full well that the referendum was advisory in nature prior to the day of the vote as we should all have known. PM Cameron said he and his government would treat it as binding, he did not, however, speak on behalf of those parliamentarians which sit on the opposite side of the house.Furthermore, the Government conceded that the question was justiciable during the course of court proceedings.

Finally, it cannot be said that the question asked on the ballot on the 23rd of June made clear what the negotiating position of the UK should be. It is therefore only right and proper that it is debated and decided upon on using our democratic process. That is that it will be debated and decided upon by the peoples representatives in parliament.

To rob the people of the of transparency and openess creates ill feeling and mistrust (although possible within a different segement of the people than you were refering to).

Kind regards,

Stefan

https://you.38degrees.org.uk/petitions/prosecute-the-daily-mail-for-contempt/manage/edit

This campaign is NOT about Brexit. Those who sign up may variously support Brexit, or Remain, or hard or soft Brexit. And this campaign is NOT designed to stifle press debate of judicial decisions.

But it is about preserving something essential to Britain’s future – the rule of law.

What unites us is that we strongly oppose the use of inflammatory or intimidating language directed at the judiciary by the press. We believe there is an existing law that makes this illegal. And we would like that law enforced.