Brexit is a process taking place in a new political and economic environment of rising protectionism throughout the western world. However, a successful Brexit strategy is still possible, but negotiating it will be less straightforward than previously thought. A ‘hard Brexit’ in the current economic and security context would leave the UK isolated in an unfavourable trade environment. Arnaud Hoyois argues a ‘soft Brexit’ is the only viable strategy in a post-liberal world.

An economically successful Brexit strategy relies on securing a ‘soft Brexit’, one that enshrines the uniqueness of the UK, permits a political discourse that revives the Anglo-American relationship, albeit allowing the UK to continue being a meaningful player in the European system. Politically, this process can be sold as a protraction of the Churchill / Thatcher / Major policies of the uniqueness of British participation in the European system. A soft Brexit could be perceived as a success by moderate Brexiters if properly presented. It would entail highlighting exit of the EU itself in a short timeframe, the end of formal direct ECJ jurisdiction over Britain, a unilateral ‘veto power’ over excessive unskilled EU immigration, opt-in options to some EU policies perceived as beneficial to specific groups of constituents and, going forward, a formally intergovernmental UK-EU relationship based on voluntary cooperation.

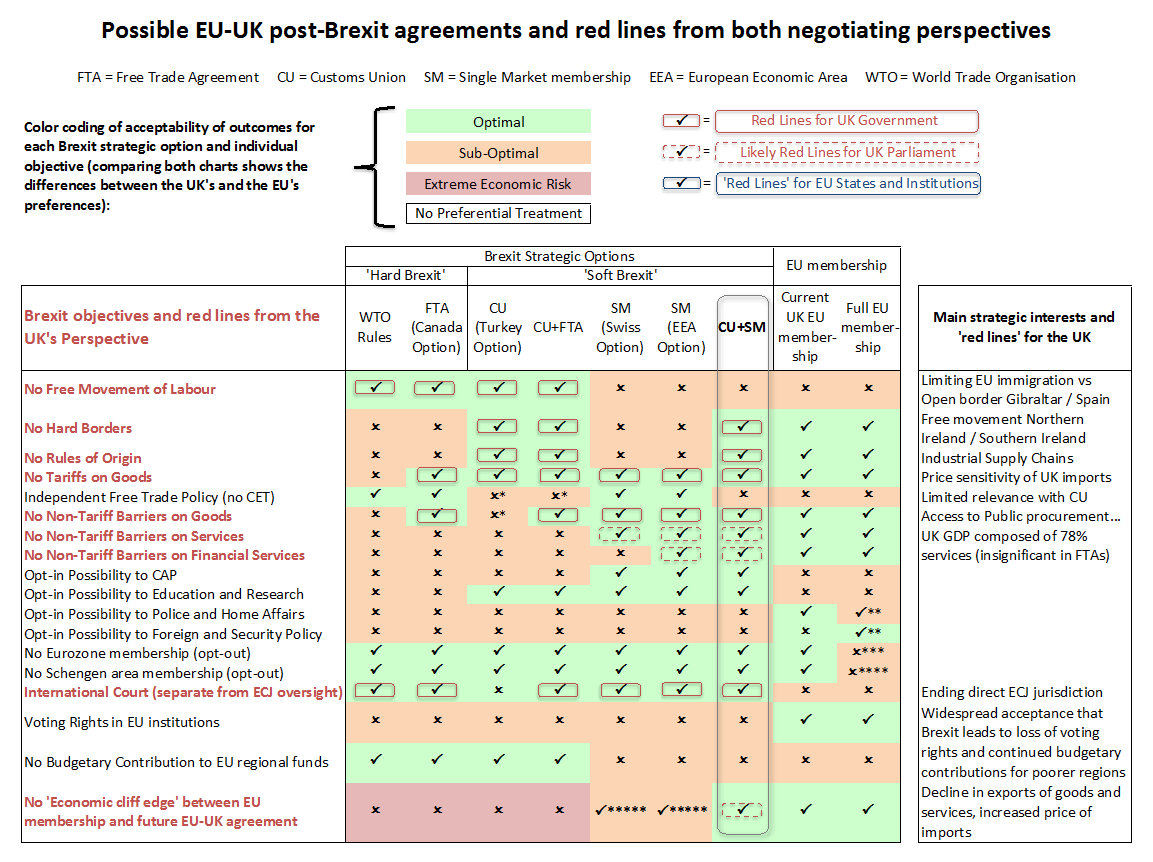

However, securing a sustainable ‘soft Brexit’ requires a deep understanding of the British political and economic red lines, as well as a series of inescapable compromises to safeguard continued full access to the Customs Union and the Single Market. Appreciably, doing so might increase the political majority in Parliament, and across the country, counting with the additional approval of moderate Remainers. The UK Parliament, the EU institutions and increasingly vocal stakeholders of this process will be instrumental in ushering in this new phase of the Brexit process.

Determining Brexit’s Red Lines

Although the British government’s negotiation strategy for a bespoke agreement with the EU has become clearer of late, it is far from optimal, therefore far from definitive. At the behest of the financial and automobile industries, as well as the Northern Irish government’s insistence, the Conservative government’s red lines during the upcoming negotiation are now apparent.

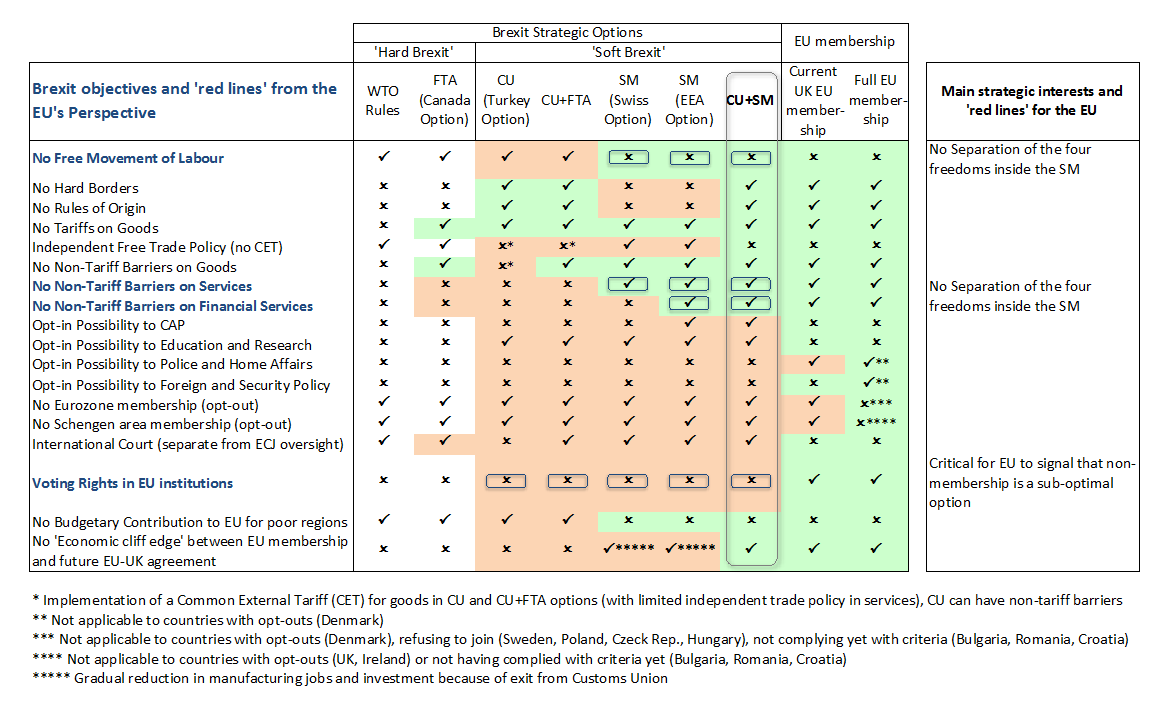

Conversely, the EU only has two red lines, the refusal to separate the four core freedoms of the Single Market (goods, labour, services, capital) for all member states (32 states in the EU/EFTA), and non-representation in EU institutions for associated European states (EEA/EFTA). In addition, there is an abundance of public information regarding prior and on-going free trade negotiations between the EU and non-member Western states, making its negotiating strategy quite predictable. The EU’s institutional and member state ratification process of such agreements has also become clearer of late, following the travails of CETA.

However there is still a missing component: the British Parliament’s red lines prior to ratifying the final agreement, and possibly prior to Article 50 notification, significantly widening the terms of the negotiation.

At the moment, limiting the freedom of movement of labour, and exiting the ECJ’s jurisdiction remain the principal motivations behind the UK government’s strategy, so as to satisfy Brexit’s core supporters. All other campaign promises of the Brexit camp, sometimes contradictory, are still up in the air, and will depend on how events unfold in the final negotiation. This is without a doubt a strategic misjudgement based exclusively on national and party political dynamics. All campaign promises will require further adjustments and compromises in accordance with the realities of international trade negotiations, international economics (growth and debt forecasts, inflation, supply chains, factory closures in key regions) and regional geopolitics.

The inevitable red line, the Customs Union

It is now evident that the need to secure continued fluidity in cross-border supply chains, in order to ensure sustained foreign investment in automobile, aeronautics and other manufacturing industries such as chemicals, has also become a red line. Any other position leading to companies relocating, reduced investment and growth prospects, as well as job losses in factories, would not be politically sustainable for any government in the long run. Moreover, less complex industries such as food manufacturers, wholesale and retail traders and textile manufacturers are also at risk from increased tariffs. Guaranteeing continued passage for goods (no hard borders) and an exemption from rules of origin controls for manufacturing industries requires membership of the EU’s Customs Union (CU). As the global trade environment changes and the readiness of G20 partners to offer alternative FTAs decreases, this red line will likely harden.

Importantly for the UK government’s current strategic thinking, the EU will not allow any cherry-picking options within a customs union. This possibility so far only applies to candidate and neighbourhood countries with less-developed economies as a temporary or permanent substitute to Single Market membership. The EU’s Customs Union with Turkey is considered incomplete and in the process of being improved and modernised. These deals are considered trade-offs meant to protect developing economies prior to entering the European Single Market (SM). Historically, the CU is the first step of economic integration. In the present circumstances, it would not be in the EU’s interest to allow differentiated access to the CU for mature economies, potentially unravelling the entire SM edifice.

Significantly, among the CU’s benefits, avoiding hard borders is acutely important for the UK, as are avoiding the bureaucratic headaches of rules of origin and tariffs for goods within the area. The important trade-off is that, because of the common external tariff, it precludes an independent free trade policy post-Brexit (trade policy must shadow the EU’s). However the CU is crucial in ensuring no hard border is created between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland, thereby fulfilling a key promise of the Brexit campaign.

Going forward, formulating a coherent strategy for Brexit, therefore, means CU membership outside of the EU (see chart of possible Brexit options and UK and EU red lines).

Equally important to CU membership is continued trade in goods avoiding non-tariff barriers within the Single Market. Any other position leading to gradual increases in the price of goods (a precursor of which is being inflicted by changes in the exchange rate) would also be politically unsustainable. This can be secured in one of two ways, by applying for continued access to the Single Market (CU+SM) or signing a Free Trade Agreement with the EU (CU+FTA). Both options allow for an international court, separate from ECJ oversight.

The CU+FTA’s key advantages are the elimination of the free movement of labour and of budgetary contributions to the EU. However, as with all FTAs, it comprises scarcely any services industries. Applicable financial services ‘equivalence’ regimes, covering only a narrow range of services, are inherently uncertain.

Because of the composition of the UK’s GDP, with 78 per cent corresponding to services industries, not benefitting from non-discriminatory principles for nationality in the EU’s services market has far-reaching economic consequences.

Attempting to carve out special consideration for British financial services in the FTA is also doomed to fail because of the EU’s red line regarding the refusal to separate the four freedoms, including services. Attempting to create a similar deal to that signed with Ukraine, Georgia and Moldova (DCFTAs), which allows ‘passporting’ for some services, although plausible, is unlikely to succeed because it is designed for developing neighbourhood countries the EU wishes to have a regulatory convergence with. The EU institutions will no doubt point out the difference with a mature economy heavily relying on services industries wishing to deviate from EU regulations and, as with a tailored CU deal, the risk of unravelling the entire SM edifice.

Above all, because of the length of typical FTA negotiations, the refusal by the EU to simultaneously negotiate Article 50 Brexit provisions and an FTA with the UK, and the inherent difficulty in agreeing on an interim arrangement, this Brexit option creates the risk of significant economic disruption in the interim period. Moreover, this ‘economic cliff-edge’, starting two years after Brexit notification and ending with final ratification of the FTA, with the risk of a fall-back to WTO trading rules in the interim (applying tariff and non-tariff barriers), is further complicated by the changing world trade environment and the difficulties for the EU to ratify deep and comprehensive FTAs, such as CETA with Canada.

Ensuring a sustainable Brexit policy: Single Market membership

A potential decrease in worldwide market liberalisation might gradually change the British perspective on Brexit. Crucially, Single Market membership is the only option that significantly eliminates tariffs and especially non-tariff barriers to services. Brexit’s economic disruption would end immediately and the ‘economic cliff-edge’ could be easily bypassed by continued full membership, until full ratification of the new agreement (in practice this would be a manageable downgrade from full EU membership to an EEA-type agreement). The UK could easily renegotiate its participation to all EU negotiated free trade agreements, customs unions and association agreements (60 non-EU countries) and freely participate to those being negotiated with Japan and several emerging countries of ASEAN.

For the UK, continued participation in the Single Market, could be achieved much in the same way as non-EU EEA states have negotiated (‘Norway option’, with close to full SM access and a dynamic approach for new regulations, using the intergovernmental EFTA Court instead of the ECJ) or Switzerland has negotiated (sector-by-sector, with limited SM access for financial services, an approach the EU dislikes because it requires updating the agreements on a regular basis). The sector-by-sector approach is unlikely to serve the UK well as it creates a permanent economic cliff-edge, if one agreement is breached, they can all be annulled.

The first trade-off is a budgetary contribution for less developed regions of the EU-EEA, applicable to EEA member states and Switzerland, which the UK Government already seems to accept as the price of doing business (even if it is currently only envisioning this contribution in exchange for access to a limited number of services industries). Under the present circumstances, these might actually prove increasingly helpful for the British government in de-industrialised areas.

The second trade-off is that any limitation to the freedom of movement of labour has been rebuffed as a principled red line for the EU institutions, as well as its member states, in both the informal statements regarding Brexit and the continuing EU-Swiss agreement negotiations. Short of the British government backing down on its proposed limitations to the freedom of movement of labour, because of the combined opposition from the City of London, international credit ratings agencies, lobbying from the British, US, Japanese, Canadian and European business associations (from all G7 members), and one or both of the houses of Parliament, future Single Market membership is unlikely. However, less significant yet greatly symbolic issues might interfere positively, such as continued free movement of labour, residents and tourists between Gibraltar and Spain, without requiring an unachievable new constitutional settlement. Moreover, it would also probably remove the risk of a new Scottish independence referendum in the medium term.

Nonetheless, the UK Parliament might have an evolving stance on this issue, eventually making SM membership an additional British red line prior to final Brexit negotiation or even ratification. This possibility might be hastened by the increasing limitations of monetary policy to tackle the fallout of Brexit and possible stagflation – depending on whether and when this occurs. As pressure mounts on the economy, possibly in terms of inflationary pressure, reduced investment, reduced growth prospects or growing unemployment numbers, it is possible that the consensus around exit from the Single Market fractures, alongside its political majority in Parliament. Lack of investment in relevant public services (mainly the NHS and subsidised housing) will only intensify the level of pressure on Parliament. Growing awareness by Unions, environmentalists, and recipients of EU social and regional funds on the financial and regulatory shortfalls from exit of the SM, might escalate the level of political pressure.

Moreover, additional limitations will become apparent when alternative Free Trade Agreements (FTA) with third countries are considered. As the PM’s recent talks with China and exploratory trade-oriented visit to India have demonstrated, FTAs with emerging countries will carry a significant political price with them. These will include genuine trade-offs for British businesses to gain increased access to foreign markets or, more disturbingly, public perception of trade-offs. They include increased migration quotas, especially for students, increased purchases of UK assets by foreigners, increased access given to foreign products in agricultural and fisheries markets, increased access to public procurement contracts in favour of foreign businesses, etc. The recent change in the world trade environment regarding multilateral trade deals might accelerate this process, as emerging countries’ find it increasingly difficult to further access the markets of G7 members.

The British public has not been prepared for the necessary give and take nature of trade agreements following exit from the SM. In a context of public discontent with free trade agreements, this will likely block any alternative strategy to SM membership. The SM membership red line from Parliament might therefore appear towards the middle, or even the end of the drawn out Brexit process, rather than the start. If the parliamentary process follows a rational course, stretched out negotiations and a proper auditory process might further emphasize Parliament’s balancing role in determining a successful Brexit strategy.

Although the notion of what is an optimal deal cannot be the same from UK’s and the EU’s separate perspectives, UK membership of the Single Market and the Customs Union is beneficial to both the UK and the EU (see optimal vs. sub-optimal Brexit objectives on chart). Brexit could occur, with the UK enjoying all the economic benefits of the EU without formal membership (thereby implementing the ‘Great Repeal Bill’), compromising by loosing its voting rights in EU institutions (but not its consultation rights through ‘comitology’ practices as used by EEA states). Theoretically, it could refuse to implement EU legislation (‘vetoing’ in Conservative terminology), with an immediate lockout from any affected SM area by the EU Commission (a possibility that already exists in the EEA treaty). This form of compromise could also be applied to waves of excessive intra-EU migration when wages are undercut in specific economic sectors. Actually tackling excessive immigration remains possible in other ways, including differentiating foreign students from foreign workers in statistics, implementing controls for work contracts and residency rights (as other EU and EEA member states do), enforcing existing SM directives allowing for only three months to seek a job before having to leave the UK, and tackling non-EU immigration in similar ways.

The American political transition is already making apparent the disparities between Trump’s campaign statements and the way the Trump administration actually conducts itself, both domestically and internationally. The same should be true of Brexit, key campaign themes will only be partially honoured due, on the one hand, to changes in the global economic environment and, on the other, to specific and gradual disinvestment risks by key economic actors when a ‘hard Brexit’ might damage their prospects. The process will eventually require a clear strategic choice, established with parliamentary oversight of the executive, preferably based on an analysis of optimal, sub-optimal and excessively risky objectives within each option.

Lastly, in the current economic environment, should Parliament fail in building a majority over the final terms of a Brexit deal, the CU+SM option could eventually become the sub-optimal interim deal, until such time as a clear majority can be built.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE. Image source: CC0 Public Domain.

Arnaud Hoyois is a researcher in European and International Studies at King’s College London (MA, MRes, PhD candidate), his research interests include European integration theory, the Common Security and Defence Policy and European military and civilian interventions in Eastern Europe and Africa.

I think the most important thing to most voters is ending free movement. Everything else is secondary.