Although some non-EU states take part in the Erasmus student exchange programme, it is unclear whether the UK will continue its participation following Brexit. Charlie Cadywould writes that educational and cultural exchanges will be vital for ensuring Britain does not close itself off from Europe, but that programmes like Erasmus need to do a much better job of encouraging those not enrolled at a university, such as vocational learners, to join in.

Although some non-EU states take part in the Erasmus student exchange programme, it is unclear whether the UK will continue its participation following Brexit. Charlie Cadywould writes that educational and cultural exchanges will be vital for ensuring Britain does not close itself off from Europe, but that programmes like Erasmus need to do a much better job of encouraging those not enrolled at a university, such as vocational learners, to join in.

The question of what kind of relationship the UK will have with the rest of Europe after 2019 continues to dominate the political debate. So far, most of the focus has been on the four freedoms and aspects of the single market – immigration, trade and regulatory divergence – while little attention has been paid to other aspects of the UK’s relationship with Europe.

Whatever the effect on trade rules and free movement, we Brits do not need to close ourselves off from our European neighbours. Broad horizons will make future generations better exporters, more mobile and give us more ‘soft power’. Cultural and educational exchange programmes will also help the UK to attract foreign students – an important export in its own right – as well as the best talent from around Europe.

The big challenge ahead is to ensure that cultural and educational exchange is available to all, and not just elites and those attending top universities. It is no coincidence that those who backed Brexit last year were far less likely to hold a degree: my recent research found this group were also far less likely to have socialised with someone from a different country in the previous six months, or even to have travelled abroad.

This isn’t happening at the moment. Take Erasmus, Europe’s flagship cultural and educational exchange programme. The programme has been shown to improve participants’ employability through soft skills, hard skills such as the ability to speak foreign languages, and in some cases work experience. It helps participants to be more confident in their abilities, more tolerant towards other people, and more open-minded and curious about new challenges.

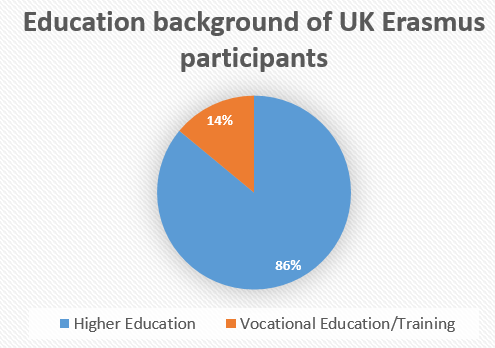

Despite all these fantastic benefits, it has a real problem reaching people from deprived backgrounds, ethnic minorities, and those who don’t go to university. The scheme has been expanded to include a vocational element, but it represents a minuscule portion of the Erasmus programme, which is still dominated by university students. If we look just at the raw numbers of Brits who participated in Erasmus to study in 2015, 11,981 (86 percent) were enrolled in higher education, compared to 1,943 (14 percent) participating in vocational education or training.

Note: Figures from 2015

However, while higher education study placements typically lasted for the best part of a year – the average length was 211 days of funded study – vocational learners typically only spent two or three weeks abroad. In fact, when the total number of days funded through Erasmus in 2015 is aggregated, less than 4 percent went to those enrolled in vocational education and training programmes.

While there is no data available on the differential impact of these forms of participation in Erasmus, it seems unlikely that a two-week trip somewhere would lead to the same levels of understanding for a different culture, language skills, soft skills, or long-lasting personal friendships that would be formed over the course of several months.

We might be leaving the European Union, but as we relinquish certain institutional ties, informal links will only become more important. The individual relationships formed through educational and cultural exchange, the attitudes, knowledge and skills it imparts, will be vital to ensuring Britain does not close itself off from the world, and continues to benefit from co-operation with our European neighbours. Rightly, though, in order to ensure there remains political support for these exchanges, they must be reformed to benefit a much wider range of people. Expanding Erasmus for skills is a much-needed first step.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE. It was first published at LSE EUROPP.

Charlie Cadywould is a Researcher at the international think tank Policy Network, which alongside its German partner Das Progressive Zentrum, recently organised a town hall event in London to discuss the future of UK-Europe co-operation with Thomas Oppermann, chair of the SPD group in the German parliament.

So funny this, coming from my old alma mater the LSE. I remember then-director Howard Davies (he was the one who resigned over the Gaddafi thesis scandal) on a visit to Lisbon talking sneeringly about Erasmus. Of course Erasmus was good for some, he said, but really that was all very 20th century. What really mattered was engaging with China, and off he went reciting a truckload of statistics about the LSE and China. But still, some would have to make do with Erasmus, the poor cousin, especially (the implication was clear) the poor universities “on the continent”.

And now we’re told, by an LSE blog, that Erasmus is good but elitist. In fact I even sense the suggestion that if Erasmus were not so elitist maybe Brexit wouldn’t have happened… I’m not quite sure about what the suggestion is, now that the UK is leaving the EU. We’re leaving but we still want to tell you that you should be doing a better job of the programmes that we don’t want to participate in any more? Oh well, good luck with your own future non-elitist China-Erasmus programmes.

All true, very true, and fair comment.

Erasmus was set up to encourage exchanges of university undergraduates, to promote harmonization of degree programmes and standards and the cooperation of academics throughout the European space. Even as founded, it was not without its detractors, especially in the United Kingdom. Partly because it was very innovative, it had no remit to create other kinds of exchange, or other kinds of co-operation, so it seems unfair to criticize it for not doing what it was not intended to do. Since most continental universities were in the 1990s much less selective than UK universities, the accusation of elitism seems a remark you should address to the British, not to the Erasmus Programme. I write as a retired academic who was an early protagonist of the programme and who was pleased to include on it any student I could, regardless of social background and regardless of grades achieved in the UK. The least socially privileged students often made the best use of the programme, not least because the richer sort were already very well-travelled. Again the charge of “elitism” seems ideologically motivated and historically unfounded.