The UK economy has been resilient so far, but faces challenges that a falling exchange rate and monetary expansion have only postponed. Outside the Single Market, trade will be more difficult. And even if – optimistically – the resulting likely fall in growth is short-lived, it takes a surprisingly long time to make up a short-term loss. Nicholas Barr explains why the economic gain from being inside the Single Market, or a functional equivalent, is considerable and argues for a new focus on skills training as Brexit approaches.

The UK economy has been resilient so far, but faces challenges that a falling exchange rate and monetary expansion have only postponed. Outside the Single Market, trade will be more difficult. And even if – optimistically – the resulting likely fall in growth is short-lived, it takes a surprisingly long time to make up a short-term loss. Nicholas Barr explains why the economic gain from being inside the Single Market, or a functional equivalent, is considerable and argues for a new focus on skills training as Brexit approaches.

Nobody can know what is going to happen in a situation with so many dimensions and so many uncertainties – and past predictions made with too much certainty and too much precision have damaged trust in ‘experts’. That said, two trends can be identified with some confidence.

For the EU27, the political imperative outweighs economic considerations

Some of the people who voted Leave did so for reasons like increasing national sovereignty, even if that had economic costs. But the same is true on the other side of the channel. For many, the European project is not merely economic. For Germany, it is central.

‘The EU is “a unique community of solidarity and values. It is our guarantor for peace, prosperity, and stability. [..] Only together will we be able to uphold our values of freedom, democracy, and the rule of law and realise our interests – economic, social, ecological, foreign relations and security – in global competition’ (Angela Merkel speaking the day after the UK referendum, Der Spiegel, 24 June 2016, translated from the German).

Though Brexit is at the top of the UK agenda, for the other EU countries it is only one item. There is Brexit, but also the Euro crisis, the refugee crisis, relations with Russia, low growth and detachment of citizens from elites. Arguably dwarfing those is the primary objective of maintaining the political coherence of the EU project and, in the short run, protecting it in the face of elections in France, Germany and Italy.

These multiple agendas dilute the importance of Brexit for the EU27, and the last creates a political imperative that the EU must provide – and be seen to provide – significantly better terms for its paid-up members than to a country choosing to leave. Putting too much weight on economic arguments is mistaken. Sanctions on Russia show that Germany is willing act for political and ideological reasons even if that harm its exports.

Trade will face increased frictions, at least in the short run. And since trade contributes to economic growth, reduced trade has negative effects

The UK economy has been robust since the referendum – a combination of the depreciation of sterling, monetary easing, and faster growth than expected of the world economy. These have postponed but not eliminated the problem. Unless the UK remains a de facto part of the single market, leaving the EU will disrupt trade at least in the short-term, as the UK moves from free trade and movement of people and capital to a situation where either or both are less free. The IT revolution accentuates the problem.

The IT revolution changes the nature of trade

Instant cheap communication makes it much easier to co-ordinate complex supply chains in which products are designed in one country, made from components manufactured in several countries and assembled in another country. In that process components cross many borders and frequently move backwards and forwards across the same border. Thus an iPhone is not made in Cupertino but is co-ordinated from Cupertino; and BMW has over 20 locations, with suppliers located in many more.

‘If there is just one anecdote that succinctly sums up the problems [of Brexit] … it is this: the story behind the crankshaft used in the BMW Mini, which crosses the Channel three times in a 2,000-mile journey before the finished car rolls off the production line. A cast of the raw crankshaft … is made by a supplier based in France.

‘From there it is shipped to BMW’s Hams Hall plant in Warwickshire, where it is drilled and milled into shape.… [E]ach crankshaft is then sent back across the Channel to Munich, where it inserted into the engine. From Munich, it is back to the Mini plant in Oxford, where the engine is then “married” with the car.

‘If the car is to be sold on the continent then the crankshaft, inside the finished motor, will cross the Channel for a fourth time (Guardian 3 March 2017).’ For another excellent summary, see the Economist 23 November 2016.

Of course, companies can and will rearrange their supply chains, but that will be time consuming. In addition, even if a company builds 100% of its product in the UK, its exports to Europe will face problems caused not only by tariffs and rules of origin that cause frictions at international borders, but also by regulatory hurdles. A key advantage of the single market is common regulations, an advantage that will be reduced outside it.

Don’t take my word for it.

‘Lord Kerr [the author of Article 50] said leaving the EU will mean that Britain’s economic relationship with Europe will be less advantageous than it is now; that its relationships with the rest of the world will be more difficult economically; that trade halves as distance doubles and that customs controls cause delays that damage modern global supply chains’ (Financial Times 22 February 2017).

‘…since the end of the Second World War, the world has sought to increase levels of trade and make it easier. A unique aspect of the forthcoming Brexit negotiations is that it is aimed at doing the opposite. These will be the first trade talks in three generations where even the best possible outcome for either side will be worse than what exists currently’ (Evening Standard, 2 March 2017).

Bringing the economics and politics together is the question of the strength of the UK’s hand in negotiating trade deals with the EU and other trading partners.

‘Britain would do itself a grave disservice by miscalculating that the EU has most at stake because Britain imports more from the 27 than vice versa. The important point is that trade with Britain matters much less to each of its partners than vice versa’ (FT, 9 March 2017).

The three largest economies are the USA, the EU and China, which produce nearly 50% of the world’s output and generate over 40% of world trade. (For a more detailed discussion, see this post by Simon Hix and Hae-Won Jun.) Countries will put greater weight on a trade agreement with the EU27 (14.5% of world GDP) than with the UK (2.4% of world GDP).

It is true that countries have made friendly noises about trade deals; and trade with those countries might well grow rapidly.

‘Britain would harmonise regulations with its former colonies rather than the European Union under new proposals for trade integration that critics have dubbed Empire 2.0’ (Guardian, 10 March 2017).

But, as Figure 1 shows, about 40% of UK trade in goods and services is with the EU and 18% with the USA. UK trade with the EU is 17 times as large as with China and 8 times as large as with Australia, Canada, India, New Zealand and South Africa combined, so Commonwealth trade, though highly desirable, is only a partial solution. Note too, that ‘friendly noises’ says nothing about what deal is on offer. The UK’s bargaining power should not be overestimated.

These arguments about trade, superimposed on the effects uncertainty will have on investment, suggest that UK trade will dip, with effects in the short and medium term.

An initial period of lower growth can take a long time to make up

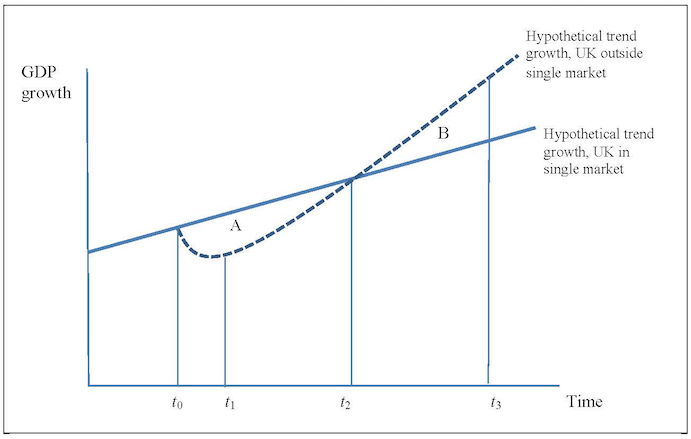

Suppose that the long-run growth path of the UK economy is shown in Figure 2 by the straight line path if the UK remains in the single market. The dotted line (UK outside the single market) illustrates an optimistic case where growth, though initially lower after Brexit, then picks up (at t1) on a faster growth path. But even if growth is faster outside the single market (itself a major topic of debate), the deeper and longer the dip (shown by area A), the longer before the UK reaches the output it would have had within the single market (shown as t2), and longer still before the faster growth (shown by the area B) has made up for the output lost during the dip.

Consider some examples. Suppose that outside the single market, UK growth is 1% lower for five years, but thereafter is 0.5% higher. We consider a GDP index, where an index of 98 does not mean that output has fallen by 2%, but that it is 2% lower than would otherwise have been the case.

As a matter of simple arithmetic, under those assumptions the GDP index will fall from 100 at t0 to about 95 at t1. With growth then 0.5% higher, the loss starts to fall, but the GDP index does not return to 100 till year 15 (t2). Continued higher growth starts to make up the loss shown by A, but the loss is not fully made up until year 27 (t3).

A plausible response is that that scenario is too pessimistic, so consider a much smaller effect, with growth rising 0.5% faster after 2 years. Even so, it takes 6 years till the GDP index has returned to 100 (t2), and 10-11 years till the gains shown by B have made up the loss shown by A (t3). Even the smaller loss is significant: the cumulative loss shown by the area A is about 6% of GDP, i.e. nearly 3 years of defence spending and close to one year of NHS spending.

The back-of-envelope intuition is simple. If GDP = 100 and growth falls below trend by 1% for 2 years and then rises 1% above trend, GDP will return to 100 after 4 years and after slightly less than another 4 years will have made up for the initial loss. Thus the economy is ‘in profit’ after year 8, i.e. 4 times the length of the initial dip. But if growth is only 0.5% above trend after turnaround, it will take till year 6 for GDP to return to 100, and nearly another 6 years before all the loss has been made up, i.e. 6 times the length of the initial dip.

What am I saying and what am I not saying? I am not predicting many years of austerity. These are examples, not predictions. Nobody knows – and with negotiations only starting nobody can know – what will happen.

What I am saying is that:

- Leaving the single market will have a negative effect such that, for a period, growth will be lower than would otherwise be the case.

- Even if the period of reduced growth is short and followed by faster growth, it takes a surprisingly long time to make up the initial loss.

- Structural change is rarely fast, so regarding the process as short is optimistic.

Can we rely on the prediction of a dip of some sort? Not in the same way as predicting that jumping off a high building will be harmful, but like predicting that heavy smoking has a high probability of damaging your health. The average effect of smoking is negative, but with variation around the average, with some people harmed more and/or sooner, and some not at all. That last fact does not invalidate medical advice against smoking. The prediction that leaving the EU, by damaging trade at least initially, is robust in the same sense.

For these reasons, a study by the National Institute of Economic and Social Research (Monique Ebell, 27 January 2017) concluded that,

‘ … leaving the single market will be associated with a long term reduction in total UK trade of between 22% and 30%, depending on whether the UK concludes an FTA [free trade agreement] with the EU or not. The estimated increases in trade from concluding FTAs with all of the BRIICS, are … just over 2% … [and] with all the Anglo-American countries (USA, Canada, Australia and New Zealand) … less than 3%. This stark difference reflects that the single market is a very deep and comprehensive trade agreement aimed at reducing non-tariff barriers, while most non-EU FTAs seem to be quite ineffective at reducing the non-tariff barriers that are important for services trade.’

The FT’s Martin Wolf, a world expert on trade, concludes that

‘The overriding objective must be to achieve the best possible deal on trade. The reality, however, is that the UK has a weak hand: without a deal, it would have its trade disrupted and relationship with the continent in tatters. Its counterparts know this’ (FT, 7 March 2017).

Possible pitfalls of new trade deals

A trade deal is multidimensional and complex. Multiple simultaneous trade deals will stretch technical and political capacity.

Trade deals that open up new markets are desirable and to be welcomed, so of course I wish the negotiators well. But it is important to understand the scale and complexity of the task. (For detailed, politically neutral discussion by a former European Commission top trade official, see How to (Br)Exit: A guide for decision-makers.)

Free trade requires agreed regulatory standards that apply not only to goods (cars, food safety, pharmaceutical drugs) but – and crucially to the UK – also to services, where regulatory design is much more complex. But the context of Brexit makes that difficult.

‘Free trade’ and ‘take back control’ do not sit comfortably together

The economist Dani Rodrik (27 June 2007) points to an ‘impossible trinity’, arguing that ‘democracy, national sovereignty and global economic integration are mutually incompatible: we can combine any two of the three, but never have all three simultaneously and in full’. If a country chooses sovereignty and democracy it cannot have globalisation, precisely because globalisation requires an internationally agreed regulatory environment.

Even when the political will is there, trade agreements have typically taken several years to complete. The issue of regulatory design points to pitfalls to watch out for.

Insufficient bandwidth. Trade deals may be badly designed because UK negotiators are too few or lack experience, since the EU has conducted such negotiations up to now. The examples of PFI deals (privately-financed schools and NHS hospitals) that have gone sour, and failed public-sector IT projects sound warning bells.

Political issues. Some trade deals may be influenced by short-term political presentation and may look good at the time, but be bad in the long-run. Again, the PFI precedent is relevant.

Bargaining power. The issue arises in various guises.

- ‘Top of the US list of demands … would be much greater access for cheap American farm products … that would undercut farmers in Conservative-held constituencies and enrage environmental and food safety lobbies because of US output of products such as hormone-treated beef and chlorine-treated poultry. US companies are also pressing for much greater access to UK public services, including the NHS’ (FT 16 March 2017).

- ‘Preliminary soundings with Commonwealth partners such as Australia and India have indicated that they have all put liberalisation of UK immigration policy near the top of their wishlists’ (ibid.).

- Some industries, for example cars, are particularly exposed.

New policies needed at home

Though trade is beneficial overall, its benefits are not shared equally – there are losers as well as winners.

My Letter to Friends (2), written directly after the referendum, argued for wider policies to address the concerns of the losers from globalisation. If a policy – in this case increased trade – benefits the economy as a whole but at the expense of some people, it is good economics, good politics and good social policy to share the benefits more fairly. The best answer to populist politics is to address the underlying problem.

Larry Summers, former US Treasury Secretary, makes the point succinctly:

‘Surely it would be better for society to … enjoy the extra output and establish suitable taxes and transfers to protect displaced workers?

‘Among other things, this will mean major reforms of education and retraining systems, consideration of targeted wage subsidies for groups with particularly severe employment problems, major investments in infrastructure and, possibly, direct public employment programmes’ (FT, 5 March 2017).

So policies to look out for should include increased investment in skills in terms both of quantity and quality. More specifically, they should include:

- More and better non-degree tertiary education and training. Britain has invested heavily in higher education but much less in other parts of the tertiary sector. The March Budget announced additional resources for training for 16-19 year olds – a welcome step, but on its own not enough.

- More generous in-work benefits in the short run, and over the medium term a higher minimum wage and reduction of zero-hour contracts and casual labour. Again, the Budget was helpful in this regard.

- Better support for people seeking work.

- Improved family support; the Budget included more free childcare.

- Policies, including housing policy, addressed at poor communities as a whole.

Though parts of the Budget show the right direction of travel, the policies need more resources and – crucially – need to be followed through in the coming years.

Conclusion

If the UK is outside the single market there are firm grounds for expecting a dip in the economy. Growth rates will be lower for a time than would otherwise be the case. The size and duration of the dip are uncertain, but structural change takes time even when the political will is there (for example, the reforms in Central and Eastern Europe after the collapse of communism), and longer if the politics are unhelpful. My intention is not to talk the country down, but to help the coming debate by offering such clarity as exists amid the smoke.

The economic gains from being inside the single market or equivalent are considerable. Martin Wolf should have the last word, pointing to the advantages of

‘ … high-quality access to the single market, via a comprehensive free-trade agreement and an “enhanced equivalence” regime for services, plus a smooth transition to such an arrangement …’ (FT, 7 March 2017).

Note

I am grateful for conversations with and comments from Iain Begg, Richard Bronk, Paul De Grauwe, Bob Hancké, Kevin Joyce, Tina Joyce, Waltraud Schelkle and Ros Taylor. Remaining errors are my responsibility.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE.

Nicholas Barr is Professor of Public Economics at the European Institute, London School of Economics.

Also by Nicholas Barr: Why Britain voted Leave and what to do about it

UK is not accepting Freedom of Movement of People so Single Market, the argument is pointless

Brexit means standing tall and being proud of being British. Yes it will cost jobs, yes it will cost money. British pride is worth more. British inventiveness will in the end prevail. We should be preparing for WTO realities and not accepting the insults from EU personages.