There was a time when the topic of the EU had little salience in British politics. Resul Umit (Vienna Institute for Advanced Studies) analysed the tweets of MPs in Ireland, Westminster and the devolved governments and found that few tweeted much about EU affairs in 2014-15, especially if they were in unsafe seats. This allowed Eurosceptical parliamentarians to fill the gap and effectively ‘own’ the subject for themselves.

There was a time when the topic of the EU had little salience in British politics. Resul Umit (Vienna Institute for Advanced Studies) analysed the tweets of MPs in Ireland, Westminster and the devolved governments and found that few tweeted much about EU affairs in 2014-15, especially if they were in unsafe seats. This allowed Eurosceptical parliamentarians to fill the gap and effectively ‘own’ the subject for themselves.

If you follow a MP on Twitter, you will often see them tweeting about the EU. It was not always this way. Before the Brexit referendum, less than 3% of MPs’ tweets were about EU affairs. MPs are not alone in ignoring the EU: research in other parliaments finds similar results. National parliaments devote less than 2% of oral questions and around 7% of all plenary time to EU affairs.

These figures have long puzzled those who see parliamentary involvement in EU affairs as a way to remedy the problem of the so-called ‘democratic deficit’ in the EU. But it would require parliamentarians to fulfil their representational functions and inform their citizens about EU affairs. So what prompts MPs to share information about the EU – or indeed not to? In a recent article (now available as an open access article in the Journal of Legislative Studies), I focused on this question, analysing over 400,000 Twitter posts by MPs from Ireland and the UK, including the devolved parliaments, between 1 October 2014 and 31 January 2015. For context, David Cameron had in 2013 promised an in/out referendum on EU membership if he won the 2015 General Election.

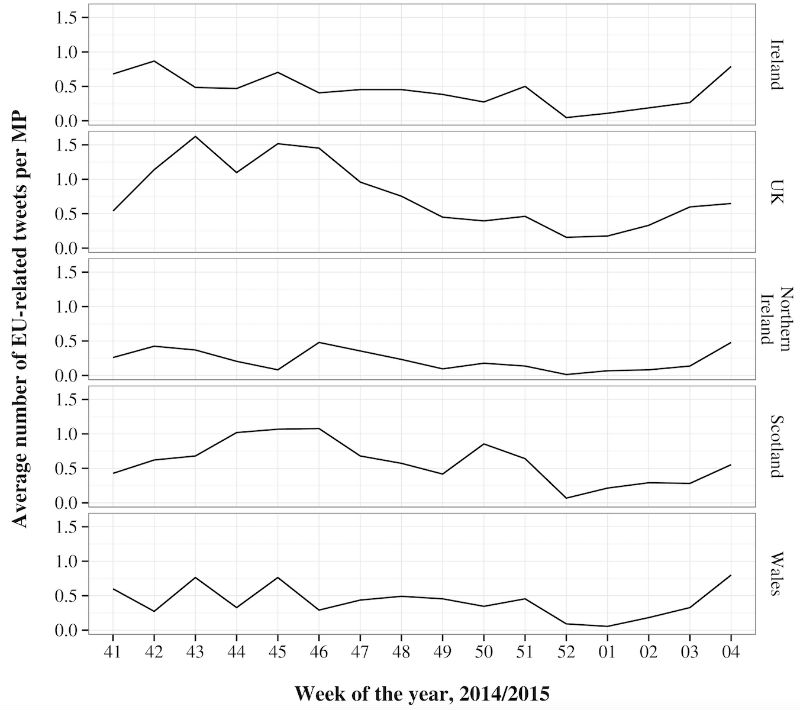

How did the communication of EU affairs unfold over this period? The figure below plots the average weekly number of EU-related tweets posted by the MPs in each parliament. It shows that EU affairs feature among the tweets of MPs from all parliaments, even during Christmas and the holiday season around week 51 and 52, but always up to certain level.

Overall, my analysis suggests that MPs are strategic about their communication, and that the low electoral benefits and the high political complexity of EU affairs are significant deterrents to tweeting about them. One consequence is that the voices of Eurosceptic MPs echo disproportionately louder on Twitter.

Most EU issues have – or had – limited salience among European citizens. For example, on average, only 3% of the electorate in the UK saw the EU as the most important issue facing their country at the end of 2014, when I conducted my study.

It stands to reason, then, if MPs are electorally unsafe and thus in need of electoral rewards, they try to stay away from communicating low salience issues such as EU affairs. Indeed, I find a positive relationship between seat safety and communication of EU affairs on Twitter. Specifically, a change from a marginal to a safe seat increases the expected number of EU-related tweets by 30%. The change from a marginal to competitive seats increases the expected number only by 20%, and this increase is not statistically significant.

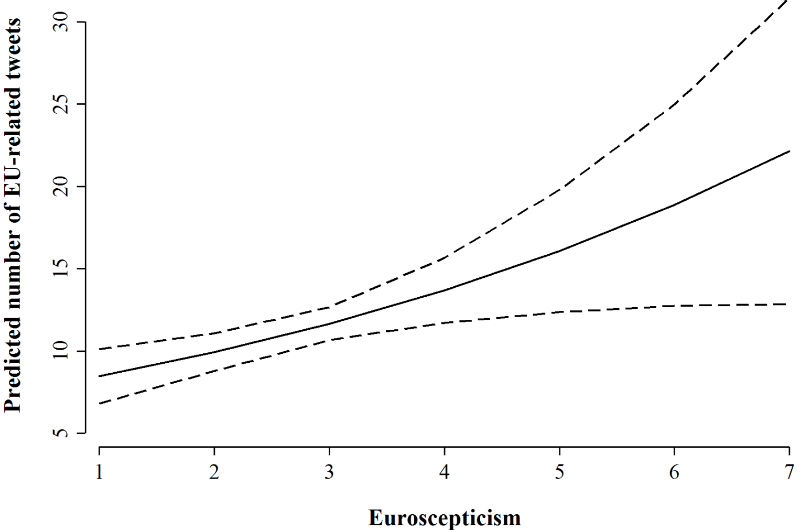

Despite its overall low salience, the EU was a salient issue for some parties, especially the Eurosceptic ones that ‘owned’ it. Every unit on the scale of Euroscepticism of a party is associated with 17.4 per cent increase in the expected share of EU-related messages by its members. The figure below shows that the communication of EU affairs more than doubles between the extremes of the scale: while MPs from parties that are strongly in favour of European integration are predicted to post roughly nine EU-related messages in four months, this number rises to about 22 messages for MPs who are members of parties that strongly oppose integration.

Eurosceptic parties could affect the communication of EU affairs without actually winning any seats. Even in constituencies where they lost, their relative success could nevertheless challenge the incumbents to address EU affairs. Likewise, for every percentage of vote share achieved by their Eurosceptic competitors, MPs were predicted to post 3.4 per cent more EU-related messages on Twitter.

The other factor that stands out is responsibility for EU affairs. MPs with a clearer attribution of responsibility – due to their membership in institutions such as national parliaments, governing parties, or EU committees – communicate EU affairs more often. The problem is that it is often difficult, more difficult than it is in regional or national affairs, to attribute responsibility in EU affairs to both MPs and their constituents. This makes it harder for MPs to claim credit for influencing them.

Here, being a member of the committee in charge of EU affairs increases the expected rate of EU-related messages by 175% compared to the members of other committees. Similarly, national MPs post 82% more EU-related messages than regional MPs. There is a relatively smaller but nonetheless significant effect of being a member of the party or parties in government: it increases the rate of EU-related tweets by 33% compared to those by MPs from opposition parties.

MPs choose what they communicate to voters strategically, and the salience and complexity of political affairs affect the way individual MPs decide that strategy. During this period EU affairs did not fit well in the strategy of many MPs. As a result, Euroscepticism had the opportunity to dominate parliamentary communication of EU affairs on social media in the crucial period just before the 2015 General Election and David Cameron’s renegotiation with the EU.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE.

Resul Umit (@ResulUmit) is a researcher in political science at the Vienna Institute for Advanced Studies. He also teaches at the Webster University Vienna.

Here we have one of the main factors behind the referendum result. British exceptionalism and inclination to regard Europe as “over there” and either unimportant or malign – something done to us rather than something which can do us good – led us to decide the EU was not for us. This was exacerbated by negative and often dishonest journalism from the likes of Boris Johnston.

Where we go from here has never been more in doubt.w

This analysis confirms my impression from reading Tim Shipman’s book about the referendum. The Remainers were probably in the majority in the political and media establishment, but lost because they lacked the passion of the Leavers. Jeremy Corbyn was unwilling to mobilise Momentum to campaign for Remain and among the prominent Conservatives, only George Osborne was 100% passionately in favour of EU membership. If David Cameron was an essay-crisis prime minister, he comes across (in the book) as being like a clever student who expects to coast a vital exam, then fails.