A notional divide between ‘anywheres’, ‘nowheres’ and ‘somewheres’ has emerged since the EU referendum. Paula Surridge, Siobhan McAndrew and Neema Begum (University of Bristol) explored attitudes towards the EU in the context of social identities, social capital and neighbourhood belonging. Counterintuitively, they found that people with a stronger attachment to their locality tended to be more pro-EU.

A notional divide between ‘anywheres’, ‘nowheres’ and ‘somewheres’ has emerged since the EU referendum. Paula Surridge, Siobhan McAndrew and Neema Begum (University of Bristol) explored attitudes towards the EU in the context of social identities, social capital and neighbourhood belonging. Counterintuitively, they found that people with a stronger attachment to their locality tended to be more pro-EU.

Imagined communities based on national and ethnic identities are important for understanding anti-EU attitudes at the time of the 2016 Referendum. National identity has been much scrutinised in relation to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, but it increasingly appears that new forms of nationalism have emerged among the White British more broadly in England.

It is already well-established that a range of structural characteristics – particularly education – have been influential in determining the EU referendum result. From the burgeoning accounts of why people voted to Leave, it has also become clear that accounts based on single-factor explanations are too thin. With a result as close as this, even marginal drivers may have had a critical influence on the overall result.

Attention has, rightly, focused on values and national identities. But what about other sources of identity and belonging? This remains less clear, despite the strong interest in social identities and in social capital in social science literature. In the wake of the result, do we actually know whether those in favour of continuing EU membership are really ‘citizens of nowhere’?

Using data from the early release of Wave 8 of Understanding Society, made available by the University of Essex to researchers with interests in what drove Brexit, we looked at the effects of social identities, social capital and neighbourhood belonging on attitudes towards EU membership.

Respondents to the survey in Wave 8 were asked how important their age and life stage, gender, ethnic or racial background, profession, education, family and political beliefs are to their ‘sense of who you are’. Alongside these measures, we include a measure of the importance of Britishness to the respondent.

To measure whether people felt they belonged to a more local area, we asked eight questions designed to capture how respondents felt about their local community.

Finally, we measured social capital in the sense of connectedness with a set of questions designed to identify how wide and diverse someone’s friendship circle was. We categorised respondents into three types: low volume/low diversity; high volume/moderate diversity; and low volume/high diversity.

Our analyses also control for a wide range of other factors: gender, social generation, ethnic group, education, occupation, household income, housing tenure, religious affiliation and attendance, and the ‘big five’ personality measures. Full details can be found in our working paper.

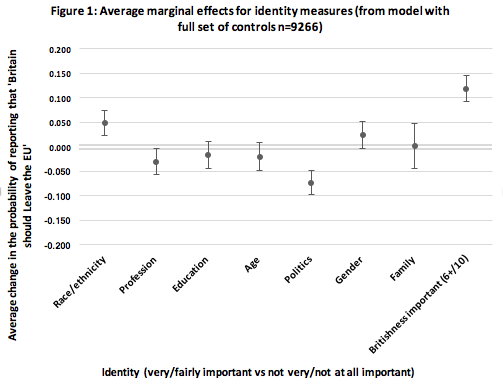

Figure 1 shows the predicted changes in the probability of answering ‘Britain should leave the EU’ where each identity type was deemed ‘very’ or ‘fairly’ important to a ‘sense of who you are’ by the respondent. Effects above the x-axis increase the probability of a ‘Leave’ response, while those below the x-axis reduce the probability of a ‘Leave’ response. The confidence interval is shown as error bars in the chart: where it crosses the x-axis, the effect of having a stronger sense of that type of identity is not statistically-significant at the 95% level.

Our results suggest that there are important social and political identity effects on attitudes towards EU membership, in addition to the strong effects of national identity already established by researchers. The largest of these effects is the importance of political identity – but ethnic identity is nearly as strong.

We also found that people who said ethnic identity was ‘important to who you are’ were more likely to hold anti-EU attitudes if they identified as White British – but this did not apply to members of other ethnic groups. To put it another way, those from White British backgrounds who said their ethnic or racial background was not important to their sense of self were less likely to be anti-EU.

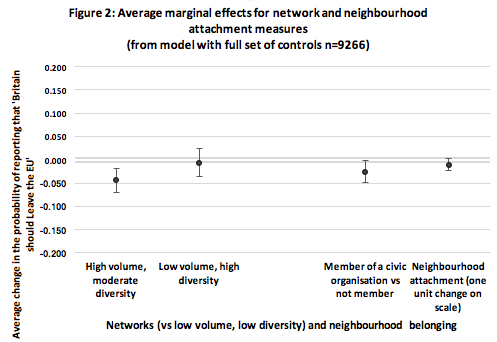

The influence of connectedness more generally is mixed. As Figure 2 shows, our measure of neighbourhood attachment was marginally non-significant, but worthy of note since stronger neighbourhood attachment predicted more pro-Remain attitudes. This is perhaps counterintuitive, given the discourse around ‘anywheres’ vs ‘somewheres’ .

When it came to personal friendships, we found that people with lots of friends who were moderately diverse predicted more pro-EU attitudes compared with having fewer friends and a less diverse network. However, among those with few friends, the level of diversity made little difference to EU attitudes. This is interesting, since network diversity is often thought to promote tolerance and pro-social attitudes – although this does not necessarily translate to EU attitudes. In this case, it seems that it is having more friends, rather than diverse ones, which matters.

People who participate in at least one civic organisation are more pro-EU than non-joiners. Together, these findings suggest that social capital is influential in explaining attitudes to the EU, but not as straightforwardly as commonly thought; and the effects look considerably weaker than those related to social identities.

What do we take from this set of findings? We found that social identities and social capital have as great an effect on EU attitudes as social class and income do. We are tapping into a range of ways of thinking about belonging. Social identification, particularly national identification, has been described elsewhere as essentially relating to an ‘imagined community’. Equally, we can think of network connections and civic participation as ways in which we belong, actively, to real communities. These are important for understanding ongoing post-Brexit divides in political attitudes. Whilst both appear to influence attitudes to the EU, in this case it is the imagined communities of national and ethnic identities that are more powerful.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE.

Paula Surridge is a Senior Lecturer at the School of Sociology, Politics and International Studies, University of Bristol.

Siobhan McAndrew is a Lecturer in Sociology with Quantitative Research Methods at the School of Sociology, Politics and International Studies, University of Bristol.

Neema Begum is a doctoral candidate at the University of Bristol. Her research will examine changing dynamics in ethnicity and voting behaviour through a case study of voting in the EU referendum.