The Good Friday agreement put to rest age-old conflicts in Ireland. It also offered hope that the reunification of Cyprus might be possible within the European Union. But lately, as Stavros Zenios writes, the “Green Line” that divides the easternmost island of the EU is viewed as a template for a soft border at the westernmost island of the Union after Brexit.

The Good Friday agreement put to rest age-old conflicts in Ireland. It also offered hope that the reunification of Cyprus might be possible within the European Union. But lately, as Stavros Zenios writes, the “Green Line” that divides the easternmost island of the EU is viewed as a template for a soft border at the westernmost island of the Union after Brexit.

European nations can sure find better ways to resolve political questions than turning for answers to the last divided capital of Europe. The Green Line is a war zone, and I was once stopped by UN peacekeeping troops when I inadvertently rode my bicycle into the demilitarised buffer zone behind the University campus. It is hard to see the Green Line delivering what Northern Ireland needs.

Nevertheless, this template is being discussed. The UK Government position paper refers to Cyprus as an example. A working paper from the Brexit Policy Institute “points to the Cyprus model” for the “free movement of goods”. Nikos Scoutaris of the European University Institute suggests that the legal arrangements accommodating the Cyprus situation could offer some inspiration if Northern Ireland (and Scotland) wish to remain in the EU. On the other hand, Michel Barnier, the EU chief negotiator, suggests that the solution for the border between Northern Ireland and Ireland cannot “be based on a precedent”.

In this blog, I review the desideratum of Northern Ireland and the Green Line arrangements, and explain why these arrangements cannot work for Northern Ireland. I point out two significant asymmetries between the two islands. While the Cyprus experience has something to offer, it does not provide a template, nor should it.

The desideratum of Northern Ireland

The Prime Minister’s Article 50 letter articulates the UK position:

We must pay attention to the UK’s unique relationship with the Republic of Ireland and the importance of the peace process in Northern Ireland. The Republic of Ireland is the only EU Member State with a land border with the United Kingdom. We want to avoid a return to a hard border between our two countries […]

This deference to the status quo is most likely welcome by all actors. However, unilateral flexibility is insufficient. The border will be subject to EU regulations on the one side and UK regulations on the other. An agreed reciprocal arrangement is needed to ensure that the border is as seamless and frictionless as possible. That’s where the Green Line enters the discussion.

Image by Jpatokal, (Wikipedia), licenced under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported.

Image by Jpatokal, (Wikipedia), licenced under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported.

Green Line flexibility

While the Republic of Cyprus territory covers the whole island, the northern part is under Turkish military control since the events of 1974. When the country joined the EU in May 2004, the application of the acquis was suspended in the areas where the Government does not exercise effective control. The Green Line separating the north dates to the hostilities between the Greek-Cypriot and Turkish-Cypriot communities in 1964, when a British officer marked with a green pencil the cease-fire line through the capital city of Nicosia. With the advance of the Turkish army in August 1974, the line was extended 180Km from the west to the east coast, with a buffer zone patrolled by UN Blue Berets. The Green Line is not considered as an external border of the EU, and Council Regulation 866/2004 defines the terms under which provisions of EU laws apply to the movement of goods and persons. This is known as the Green Line regulation.

The Regulation adopts “special rules concerning the crossing of goods, services and persons, the prime responsibility for which belongs to the Republic of Cyprus. As these areas are temporarily outside the customs and fiscal territory of the Community and outside the area of freedom, justice and security, the special rules should secure an equivalent standard of protection of the security of the EU with regard to illegal immigration and threats to public order, and of its economic interests as far as the movement of goods is concerned. “The Government is required to “carry out checks on all persons crossing the line with the aim to combat illegal immigration”.

These excerpts present the hard side of the Regulation. There is a kinder, gentler, side that encourages trade between the north and the areas where the Government exercises effective control. Goods validated by the Turkish-Cypriot Chamber of Commerce as originating at the north can cross freely the line. It is this flexible provision that inspires potential arrangements for Northern Ireland.

Regarding persons, EU citizens and third-country nationals who are legally residing in the northern part of Cyprus can cross the line. So does anybody who enters the island through the Government controlled areas. But what happens to those entering the northern part of the island through Turkey? The Regulation states that “while taking into account the legitimate concerns of the Government of the Republic of Cyprus, it is necessary to enable EU citizens to exercise their rights of free movement within the EU and set the minimum rules for carrying out checks on persons at the line and to ensure the effective surveillance of it, in order to combat the illegal immigration as well as any threat to public security and public policy.”

This masterpiece wording of creative ambiguity. EU citizens who enter the island through the north can cross the Green Line by showing an ID card or passport. Third country nationals are, in general, denied entry. Why this distinction? EU residents can enter freely the island, and the fact that they may have arrived through Turkey is not used against them. Third country nationals need to obtain an appropriate visa and have it checked at a legitimate port of entry. The Government does not wish to relegate control of its borders at Green Line crossing points.

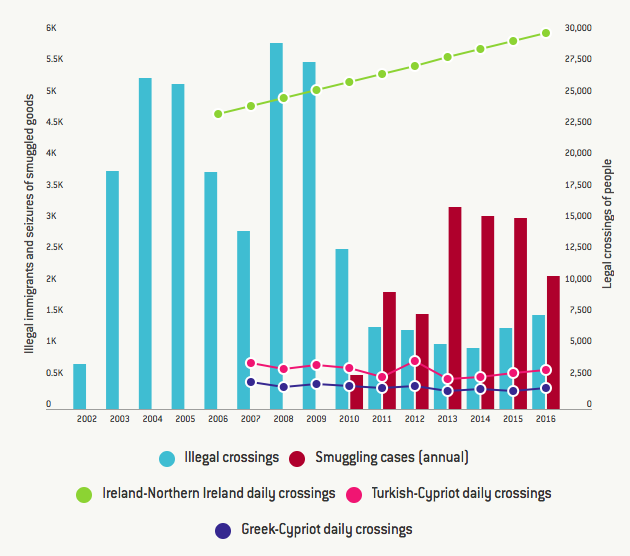

The Regulation asks “the Commission shall report to the Council on an annual basis […] on the implementation of the Regulation and the situation resulting from its application”. From these reports, we can monitor the experience over the last 14 years (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Illegal immigration and smuggling across the Green Line, and the crossing of persons across the Green Line and the Ireland-North Ireland border.

Note: Data for illegal immigration, seized products, and crossings of persons across the Green Line from Commission reports. Crossings in Ireland for 2006 from the Centre for Cross Border Studies and for 2017 from FactCheckN. and linearly interpolated in between.

The Green Line is not so green

While flexible, the Green Line is far from being the soft border required for Northern Ireland. There is a small number of “official crossing points” where Republic of Cyprus police enforces the Green Line regulation. Similarly, Turkish-Cypriot “authorities” —the “Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus” unilaterally declared its independence in 1983, but is recognised only by Turkey— exercise, in general, symmetric controls for persons and goods crossing from the Republic controlled territories.

Why is a hard border unavoidable? Leaving aside the complexity of the military conflict with Turkey, one significant goal is to stem illegal immigration from the north. Even with strict police controls and fenced up the buffer zone and military patrols across the line, there has been significant leakage. The number of irregular migrants is reported in Figure 1. While illegal crossings are less than 0.5% of the legal crossings, the leakage is significant for an island with a population about 1 million. To put these numbers in perspective, Cyprus was slated to receive a maximum of 300 Syrian refugees, and the illegal immigration across the Green Line is more than five times this quota.

The official crossing points also serve for verifying that goods transported are produced in northern Cyprus and can be traded without duties. Turkey, that enjoys free trade with the north of Cyprus but is not EU member, cannot export its products to the EU through the Green Line. However, smuggling of goods remains widespread. The reports of the Commission reveal very little trade across the Green Line (4–5mil EUR per annum), but also seizures of smuggled goods (Figure 1). A report by Sapienta Economics reveals much higher consumer spending (33.5mil. EUR in 2016), which is about .15% of the combined GDP of the economies on both sides of the divide. Smuggling is mainly due to price differentials and the higher tax on tobacco products in the Republic of Cyprus. There is also smuggling of agricultural and animal and dairy products, and products violating intellectual property rights. All trade is intra-island.

The Green Line model for Ireland

The flexible arrangements of the Green Line for the movement of goods, prompted the Brexit Policy Institute to propose empowering the Northern Ireland Executive to identify goods as originating in Northern Ireland (and not simply travelling through Northern Ireland from the UK or a third country). The EU could allow these certified goods to enter the EU market via the Republic of Ireland and to be treated as EU goods. This arrangement could indeed work, although certificates would need to be checked at “official crossing points”.

How would the UK reciprocate? According to the Brexit Policy Institute:

The UK could allow such [certified] goods enter the UK market as “domestic goods”, and this would allow the UK to present this arrangement as a symmetrical one.

This is hardly a reciprocal arrangement with the EU, it is more like eating your cake and having it too. A reciprocal arrangement will require products originating in the Republic of Ireland to cross freely into Northern Ireland and the UK. And this raises some hard questions:

- Could the Northern Ireland Executive discriminate against products not produced in Northern Ireland, according to UK law? Possibly yes, and the Executive will be willing to do it to promote Northern Ireland exports to EU markets.

- Could the Republic of Ireland discriminate against products originating in other EU member states? Most likely not, and the Government would rather be unwilling to make special efforts for a small trading partner.

A practical reciprocal arrangement would be to treat all EU products entering Northern Ireland from the Republic of Ireland as domestic goods. But such an arrangement will be a back door entry for EU products into the UK.

Furthermore, if the UK wishes to “take back control of its borders”, as one of the objectives of Brexit, it cannot avoid the hard feature of the Green Line when dealing with crossings of persons. Only an agreed reciprocal arrangement that anyone in the Republic of Ireland can cross into Northern Ireland, and conversely, will render a hard border unnecessary. But such an agreement will be a back door entry of EU citizens into the UK.

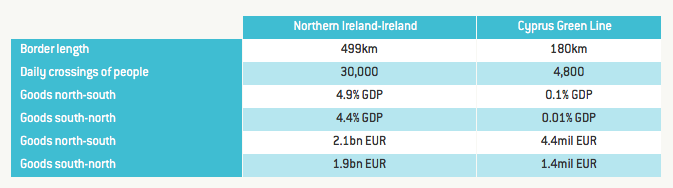

If anybody harbours hope that the Green Line template could still serve Northern Ireland, let us not forget the scale differences between the two islands. Crossings of persons and goods across Northern Ireland-Ireland border is an order of magnitude bigger than crossings across the Green Line.

Table 1.

Note: Data on Northern Ireland trade with the Republic of Ireland from Bruegel and authors calculations. Trade and persons crossing the Green Line using data from the Commission report for 2016 and authors calculations. Persons crossing the Irish border from FactCheckNI.

Asymmetries between the cases of Northern Ireland and Cyprus

Some aspects of the Green Line regulation relating to goods could indeed provide inspiration for a Northern Ireland border post-Brexit. However, such arrangements require official crossing points, which everybody agrees should be avoided in Northern Ireland. This salient point is conspicuously absent when the Green Line is invoked as a model.

There are two significant asymmetries between the cases of Northern Ireland and Cyprus. These are worth bearing in mind, as they delineate what the Green Line template could and could not achieve.

First, the Republic of Cyprus is a member of the EU and the Green Line regulation allows part of its territory not under Government control to enjoy membership benefits. The interlocutor of the EU is a member state. In the case of Northern Ireland, arrangements are sought for a territory that will be under the control of a non-member state (UK). There will be no member state interlocutor, and the EU will have to deal with a region. The case of Cyprus is easier in this respect.

Second, north Cyprus does not have officially recognized State authorities. Arrangements that require a sovereign —such as customs control, issuance of drivers licenses, and vehicle roadworthiness certificates— can not be worked out between the Republic of Cyprus and the north. The situation between the UK and Northern Ireland, and the Republic of Ireland is easier in this respect.

Setting a good example

Where does this discussion lead us? The hope that Green Line can be a role model is, in our opinion, misplaced. No country divided by force, and staying divided for 43 years, can be a role model. The Green Line is an example of exceptionalism that needs to be normalized, not to become the norm. There may be consensus on the desiderata for Northern Ireland, but they cannot be achieved using the Green Line model.

If the UK and the EU show sufficient imagination to find a solution, that could become a template for Cyprus. But making the Green Line of a divided Cyprus the template for Ireland will create more problems than it will solve. It will be going backwards.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE. It was originally published on Bruegel and the BPP.

Stavros Zenios is a Visiting Fellow at Bruegel, as part of a Marie Curie Fellowship. He is a professor of finance and management science at University of Cyprus, Adjunct professor at the Norwegian School of Economics and Senior Fellow at the Wharton School, USA.

The Green Line in Cyprus is a hard Border with supervised crossing points. Both the N. Ireland government and the Republic of Ireland reject a hard border, so it isn’t going to happern