Young EU migrants’ worries about their post-Brexit immigration status and future are not a concern for themselves alone, writes Aija Lulle (University of Sussex). They reveal an acute loss of trust in the UK and its value systems – signified by the broken ‘word of honour’ – and put social relations between migrants and native-born Britons at risk.

Young EU migrants’ worries about their post-Brexit immigration status and future are not a concern for themselves alone, writes Aija Lulle (University of Sussex). They reveal an acute loss of trust in the UK and its value systems – signified by the broken ‘word of honour’ – and put social relations between migrants and native-born Britons at risk.

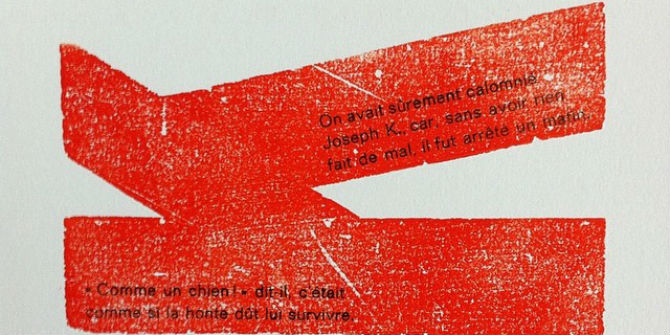

Immediately after the EU referendum, speculation, fears and uncertainties emerged among EU migrants living in the UK: who would qualify to remain, who would be ‘forced’ to leave, who will decide to leave the UK? Legal status related to the length of stay in Britain, travel patterns, meticulous collection of payslips, health insurance – these are just a few of the things that felt, to some, like a Kafkaesque nightmare, while going unnoticed by others. But does this reveal a generalised indifference toward bureaucratic struggles and the uncertain future of a neighbour, work colleague, or schoolmate?

As one of a team of researchers at Sussex University, between 2015 and 2017 I studied European youth mobility to the UK. The referendum and its aftershocks came when we had almost completed our interviews. We re-interviewed half of our research participants and have stayed in touch with many up until the present. Some have left, not only due to Brexit but for a combination of personal and professional reasons against the background of uncertainty. Some have obtained residence permits, and others are still collecting documents. Yet something bigger than just solitary struggles came out of these repeat interviews: most of them said they consciously avoid media or discussing Brexit in order to protect themselves from negativity. They had to block former ‘friends and acquaintances’ on social media to avoid abuse. Most have lost trust in British politics and bureaucracy. This is not simply about emotionally upset individuals; disconnection, and erosion of trust may indicate a wider social condition, potentially destructive to a vibrant, meritocratic and open society – which many took Britain to be when they arrived here.

I will briefly sketch out some of the ‘warnings’ that emerged as we talked our research participants. They illustrate four rotating axes which contribute towards sociality and democracy, or, conversely, reveal how distrust permeates various levels and encounters in society.

Mediatised moralities

According to some of our interviewees, the stirring of anti-immigrant sentiments took place, broadly, through the media.

Peter, Slovak: What troubles me is also the fact that… at least from what I understand from the media… is that most “Brexiters” voted to leave because of immigration. It’s just something that… despite the perpetually negative rhetoric in the media regarding immigration, it’s just something that you almost don’t expect to win the vote in 21st-century Britain. It’s something you can say you expected in Slovakia… [laugh] you know what I mean? But not here… Well it’s not just here – the world has gone mad… Trump and other anti-immigration views are becoming more and more popular everywhere.

While the British press has been sharply divided and political issues have long been hotly debated, the loss of trust is linked to wider trends: political decisions in Britain, across the Atlantic, and back into memories of how our trust in sensible political decisions got eroded in a mish-mash of post-socialist, ethno-nationalistic identity politics.

Bureaucratic moralities

Niklavs from Latvia tried to apply for the citizenship, but:

This sense of helplessness is quite tough. I applied for the citizenship and they asked me for the proof that my English language skills are sufficient. I submitted the test I did during my first year in London, but I got rejected. They said the test was carried out by a testing institution which is not recognised by them [Home Office]. If rejected, you can try again, but it all costs, and all requirements are vague. It is like a lottery, you do not know if you would be rejected. It feels as if they have some indicators to fill; how many of us, in numbers, they have rejected. (..) Even if some steps become clearer, I believe in the British ‘word of honour’ no more.

Does the chaotic disciplining of migrants into ‘permanent resident’ and ‘settled’ statuses reveal a fundamental distrust?

Personal undercurrents of intolerance

Could one hope that the status of ‘citizenship’ might bring dignity and acceptance?

Arnis, also Latvian, a citizen of the UK: I was shocked about some of my Facebook friends immediately after the Brexit. A person with whom I was sitting at the next desk and chatting with daily, suddenly wrote me that I must be grateful that I am allowed to live here, and the fact that my children were born here was a burden to the National Health Service. I was utterly surprised how people who were so close to me could hide their contempt for so long.

Moralities shape future plans

Then maybe leaving the UK is an option? But for whom? Monika, a mother of two originally from Poland, is highly educated but she has been a housewife for the past five years in the UK. Her interview extract below recounts her past, current, and possible future mobilities. She is open-minded about the family’s future, since her partner works in the high-demand pharmaceutical industry:

Brighton is very safe place compared to the rest of the country, so it’s good for now. But how will it look in few years’ time?… For what England allows and their attitude towards all these things [referring to Brexit and immigration], it could be really hard to live here in few years’ time and really dangerous. So maybe I will try to migrate again… I don’t know, to the US? I’m not sure, but New Zealand, Australia are the places that I know won’t be a problem to move regarding my husband’s job; we will be able to migrate there.

Brexit has not changed the esteem she has for her husband and subsequently, their family and lifestyle. All she says for certain is that the life “back home” in Poland is not for her any more. Such experiences have already been documented. In the global capitalist system, this ‘desirable’ migrant family can choose where to go. In the meantime, Monika’s wider reflections on deteriorating attitudes towards migrants are not so much fearful as pitying of the UK. Moralities are all-encompassing, and reach into one’s future plans and ambitions about where to live.

As far as migrants’ individual and familial mobility is concerned, the Brexit discourse of wanting only the ‘brightest and best’ of migrants comes with a paradox. Quantitative studies in OECD countries reveal that it is generally the lesser-skilled who are most keen to secure permanent residence. Thus policy attempts to “bind” people to a place tend to reduce overall human capital stock rather than increase it. In terms of age and family status, younger migrants, without children, without a permanent job or a settled home, can technically leave the country more easily than older, more established migrants. But how will Brexiters be able to rebuild the trust that brought EU migrants here in the first place?

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE. It is partly based on a forthcoming manuscript, co-authored with Professor Russell King, and research assistants Veronika Dvorakova and Aleksandra Szkudlarek.

Dr Aija Lulle is a postdoctoral tutor in Geography at the University of Sussex.

If people bring needed skills to the country and are working, or are self sufficient and are not a net drain on the economy, then they will always be welcome. What we don’t need are people from abroad coming here and being a burden on the state, we have enough home grown people doing that and shouldn’t be importing more.

‘Rebuild the trust’ between the EU people and the Brexiteers. Well I say what about the trust between the British people and their own government – which has been hopelessly eroded by the National Health waiting lists and delays, nobody speaking English in the street – well hardly any – rubbish colleges – provincial towns in a total state. Stuff the EU people for the time being – we need to rebuild our own trust first. the EU people are not high on our list of priorities at the moment – we are ourselves thank you very much.

Becoming part of the United States of Europe was progressing without engaging the people who were likely to be affected.

Deceitfully changing the cover of the written EU Constitution so it became the Treaty of Lisbon was the final straw for many.

Change is difficult. Many doubters demanded promises in 2016 that could not reliably have been made until the EU27 agree.

Will we now find a way of engaging everyone affected or will we continue demanding embryonic plans and promises and then accusing each other of lying or calling each other liars before the negotiations are done?

Until our negotiations are complete we should not demand, make or rely on Brexit “promises”.