British young people will shortly lose their EU citizenship. Since 2015 Sam Mejias and Shakuntala Banaji (LSE) have explored what this citizenship means to them and to what extent they are able to exercise it. The resulting picture of young people’s active civic and political contributions includes some surprising findings.

British young people will shortly lose their EU citizenship. Since 2015 Sam Mejias and Shakuntala Banaji (LSE) have explored what this citizenship means to them and to what extent they are able to exercise it. The resulting picture of young people’s active civic and political contributions includes some surprising findings.

One of the EU’s longstanding goals is to ensure young people are involved in representative democracy. In practice, this means ‘bridging the gap’ between young people and EU institutions, and improving dialogue so as to build trust and encourage active engagement with the EU. The LSE was part of a consortium of eight universities in the Czech Republic, Estonia, Germany, Greece, Italy, Portugal, Sweden and the UK which sought to find out how academic literature across various disciplines has conceptualised and studied active citizenship for young people in a European context.

With funding from the European Union Horizon 2020 Young 5a programme and bringing together scholars from different disciplines (psychology, political science, sociology, media and communications, and education) the Constructing Active Citizenship with European Youth (CATCH-EyoU) project aims to identify factors, meanings and practices that influence different forms of youth active engagement across Europe. Against the backdrop of Brexit, and led by UK project director Shakuntala Banaji, LSE’s team in the Department of Media and Communications has been working on the project since September 2015. We’ve used a range of empirical approaches to gather, collect, generate and triangulate data about the different factors influencing the perspectives of young people on the EU, and to build a picture of young people’s active civic and political contributions in Britain. Our findings, along with those from the full eight-country consortium, will be explored in our forthcoming seminar on 31 May 2018 at LSE’s Department of Media and Communications.

What does ‘European citizenship’ mean?

We analysed over 700 texts about citizenship, engagement, participation, activism, youth political socialisation, political and civic engagement – and found a significant gap in literature on both the concept of European citizenship and on the activities, practices and position of young European citizens. Drawing on our discussions about competing definitions of youth active citizenship and European citizenship, we highlight the normative implications of the disjuncture between dominant conceptions of citizenship accepted by authorities, and critical accounts of youth active citizenship.

A dearth of meaningful policies

We used qualitative document and discourse analysis and in-depth semi-structured interviews to explore how government policies conceptualise young people and their citizenship. In the UK, our study found a dearth of meaningful and integrated policies to advance young people’s citizenship, and a significant gap between how public policies understand and respond to it and the reality of young people’s needs, context and diversity.

Inadequate media representations

Perhaps unsurprisingly, our extensive thematic content analysis of the representation of young people and their citizenship in UK news and entertainment media showed that, within our selected sample, young people are still interpreted through narrow and reductive discursive lenses. They are overwhelmingly conceptualised as vulnerable and problematic, but also as digitally savvy ‘service users’ with considerable voice. Neither of these views serves their social, political and economic interests or helps make them critical, active citizens.

Since the referendum, support for EU institutions has risen among the young

In a two-wave longitudinal quantitative survey of around 2000 young people across the UK, we found significant evidence that young British people are socially conscious, tolerant of different languages and cultures, and possess a strong commitment to democratic structures and expected normative forms of participation (voting, volunteering, and online activism). We also found that since the EU referendum, young people have expressed more support for EU institutions and less for UK institutions. Additionally, when compared with the samples of the other seven EU countries participating in the survey, UK young people were among the most pro-European and among the most welcoming of migrants and refugees.

Solidarity and a strong desire for change

The qualitative survey and ethnographic strand of the study, which was led by LSE, gave us the chance to explore the meanings and practices of ‘successful’ youth active citizenship in depth. We began by mapping the youth active civic organisations in which young people participate, finding a wide spectrum of topics, motivations, and types of initiative. Moving from this mapping exercise which was largely textual and relied on the documented aspects of youth civic initiatives, we asked questions about what motivated the young people involved in them. Our ethnographies of Momentum and My Life My Say provided fascinating examples of grassroots youth citizenship practices that are trying to work within and fundamentally change institutional politics in the UK. The timing of our fieldwork in 2017 gave us a front row seat as young people mobilised during the June 2017 snap general election, revealing innovation, solidarity and passion for change – which has been likened to a ‘youthquake’ in both British media and academic scholarship.

Join us at a public seminar on 31 May at 6.30pm to explore the highlights, insights and policy recommendations of our study. Further publications are coming: watch this space.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE.

Shakuntala Banaji is Associate Professor in the Department of Media and Communications at LSE.

Dr Sam Mejias is is a Postdoctoral Research Officer in the Department of Media and Communications at LSE for CATCH-EyoU. He is also a co-Investigator on the Wellcome Trust (UK) and National Science Foundation (US) funded project ‘Science Learning Plus: Creativity and Equity in STEM Learning’.

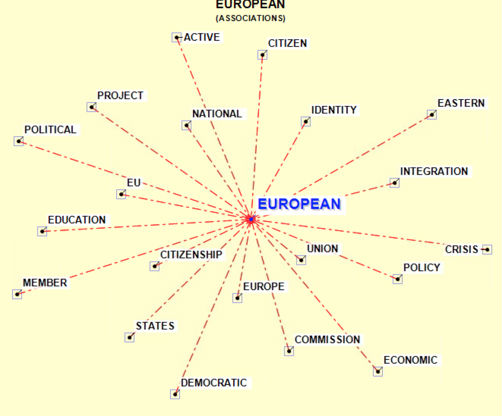

The word association chart shown appears very interesting but how does it express associations? Do the lengths of the radial lines correspond to the frequency of association or does the nearness to the word ‘European’ indicate a ‘closer’ association? Your audience clearly needs to know.

‘One of the EU’s longstanding goals is to ensure young people are involved in representative democracy. In practice, this means ‘bridging the gap’ between young people and EU institutions, and improving dialogue so as to build trust and encourage active engagement with the EU.’

I don’t agree with that. Substantially, being involved in representative democracy would involve being active at the level of national citizenship. Look at the Irish referendum on abortion, the protests in Poland over that issue, young people’s involvement in EU critical national parties in Italy for example. In similar vein, what has Momentum as a case study got to do with the EU in this context? It is contesting national politics. If anything, it has benefitted from the populist opening up of politics associated with Brexit. Momentum is a campaign to support Corbyn’s politics, and (formally at least) they accept EU citizenship is over with Brexit.

Let’s not conflate national citizenship with EU citizenship. It is the former that offers the potential for change, Brexit being a case in point.The latter, as the Italians are funding out, represents a technocratic imperative against democratically decided change.

I can see no valid basis for believing a young person’s discursive and political world need be anchored exclusively to the nation-state in which they were born or reside.

Of course that is true – national democracy has never precluded internationalism or thinking of international politics. But it is through democratic politics, a politics that operates through the nation state, that people can act upon the world. People did that when the UK joined the EEC, and they did that when they voted to leave the EU.

“With funding from the European Union”

The EU doesn’t have any funding of its own to fund anything.