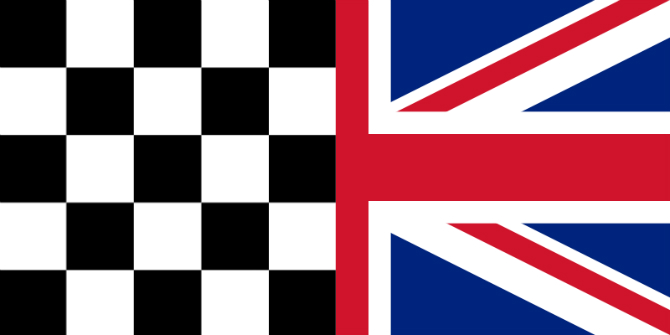

Daniel Kenealy and Seán Molloy outline the ‘Chequered’ path(s) to Brexit that the PM might take. They argue that the choice is between a soft and ambiguous exit or a hard and unattainable one. The unsatisfactory nature of each option may lead to the unravelling of both, and the implications may be enormous for the UK, they conclude.

Daniel Kenealy and Seán Molloy outline the ‘Chequered’ path(s) to Brexit that the PM might take. They argue that the choice is between a soft and ambiguous exit or a hard and unattainable one. The unsatisfactory nature of each option may lead to the unravelling of both, and the implications may be enormous for the UK, they conclude.

The Conservative resignations in the wake of the Chequers summit have made the stakes of Brexit much clearer for the Conservative party. Where once there was pretended unity, Chequers brought sharply defined division. There are now two clear factions on Brexit in open opposition to each other. Theresa May’s fate, and that of Brexit, will depend on which emerges victorious. Post-Chequers, therefore, we are left with a tale of two Tory Brexits: one with a clear path to an unknown destination, the other with a destination, but no clear path by which to achieve it. The unsatisfactory nature of each approach may lead to the unravelling of both. The implications of this conflict are enormous for the UK.

The Prime Minister: a clear path to an unknown destination?

May is in a stronger position than many recognise or are willing to admit. Chief among the factors in her favour is parliamentary arithmetic. In May’s own party there is no majority in favour of hard Brexit and Her Majesty’s Opposition is closer to her position than her erstwhile hard Brexit companions. In the event of a Conservative revolt, she can count on Labour support effectively securing a result much closer to Chequers than the Free Trade utopia position favoured by Davis and Johnson.

What explains May’s suddenly decisiveness? With various economic alarm bells ringing with ever louder intensity, May was forced into the most difficult dilemma facing any modern Conservative leader: how to balance the Eurosceptic ideological preferences of her party rivals and their supporters against the electoral damage caused by indulging their preferences? The country as a whole is not as enthusiastic as diehard Tory members for a Brexit that threatens economic hardship for millions. A soft Brexit delivers enough separation from the EU to satisfy moderate Brexit voters, while also bringing on board Remainers worried about the consequences of fracturing links with the EU completely. May’s policy is a classic compromise position that recognises the result of the referendum but also accommodates the concerns of the defeated side. May’s solution also has the benefit of relegating to the margins the extremes of hard Brexit and the Remainer refuseniks, thereby re-establishing the Tories as a party of the middle ground. If the wishes of hard Brexiters must be sacrificed on the altar of electoral calculation, then so be it.

The problem with May’s position lies outside Westminster. The EU is likely to reject the Chequers proposal as ‘cherry-picking’ and re-emphasise the choice between what is termed ‘Norway-plus’ – continued membership of the single market and the customs union thus resolving, amongst other things, the conundrum of the Irish border – and a more basic trade deal. May and her cadre of supporters and advisors are perfectly aware that the EU is likely to reject the Chequers proposal, but its significance lies more in its politically symbolic crossing of the Brexit Rubicon than in its specific contents. May is playing for time and retaining an ambiguous position couched in ambivalent terms. She is at least signalling to Brussels the direction in which the political wind is blowing, and more importantly, the way in which it is not blowing. That the EU now feels free to announce that a deal on separation is 80 per cent achieved indicates that it approves of May’s stand, granting her a certain amount of political capital.

The difficult decisions about the future UK-EU relationship could be kicked on into the transition period. The declaration about the future relationship, which will accompany the Withdrawal Treaty, will likely be vague and non-binding. Having made a symbolic, but decisive, nod towards a ‘softer’ form of Brexit, a ‘can-kicking’ strategy would avoid committing to anything close to ‘Norway-plus’ before 29 March 2019. May would survive, perhaps, to pick up the battle again during the transition period.

The Conservative hard Brexit MPs: a destination with no clear path?

Although a parliamentary minority, the hard Brexiters are significant in that they embody the political will of zealous Conservative party members. Their numbers in parliament are sufficient to force the Prime Minister into unholy alliances with opposition parties. But to challenge May’s premiership directly could reveal their weakness where it counts, i.e., in parliament. The hard Brexit faction cannot be certain of defeating May in a vote of no confidence. They also lack a viable candidate to unify them, and to present more than one candidate would be to split the ‘movement.’ Even if they installed one of their own in 10 Downing Street they would be snookered in early 2019 when the Commons would reject a hard, or a ‘No Deal’, Brexit.

Strategic hard Brexiters understand that the major battle remains exiting the EU on 29 March 2019. They may very well give Theresa May her head in the short to medium term and hope to hijack the transition period instead, while still proclaiming hard Brexit in the interim as their ideal. The best play for the hard Brexiters might therefore also be to push any major decisions about the future UK-EU relationship further into the transition period and hope for political events to turn in their direction. Some, like Michael Gove, have opted to stay in government, keeping an eye on developments from the inside whilst retaining an ability to create turmoil.

Where do we go from here?

The first casualty of Chequers is the ‘cake-and-eat-it’ fantasy Brexit that pedalled the notion that the UK could have access to the benefits of EU membership while avoiding the costs. Only two Brexits remain: an extremely risky, but potentially rewarding scenario in which the UK prospers as a beacon of free enterprise, and the economically safer, but politically difficult Brexit that ties the UK to the EU.

The Prime Minister may have overcome the Brexit zealots for now, but she faces a new and greater problem, one that gets to the heart of Brexit’s ‘mad riddle’: what is the point of leaving the EU only to be subject to EU laws and regulations with no representation or influence? Is soft Brexit an adequate solution or merely a staging post to a more logical conclusion: that the real options reduce to hard Brexit or no Brexit at all? The Prime Minister may conclude that the only way to navigate this stark choice is through a referendum, in which the electorate is clearly apprised of what is at stake and that the responsibility for what follows is theirs, not that of the Conservative Party. Were she to do so, the Prime Minister may deliver or deny Brexit, but she would certainly save her party.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the LSE Brexit blog, nor the LSE

Daniel Kenealy (@DanielKenealy) is a Lecturer in Public Policy at the University of Edinburgh.

Seán Molloy (@SeanMolloyIR) is a Reader in International Relations at the University of Kent.