The concept of a frictionless border is a constant theme of the Brexit debate. But as Anna Jerzewska (British Chambers of Commerce) points out there is no such thing as completely frictionless trade across a border. Brexit potentially adds new border formalities and checks when moving physical goods across the border, and these extra formalities add to border friction. The amount of additional formalities will depend on the “flavour” of Brexit – “hard” Brexit currently looming in just a few weeks’ time will mean maximum additional formalities and friction.

Will these additional formalities cause long delays at ports? Can technology solutions be used to introduce or help simulate a frictionless border? Could we have an “e-border” where trucks carrying goods speed through the border without having to stop? Can we, in fact, have a seamless/frictionless border? Answering any of these questions requires an understanding of what happens at the border, and how border friction arises in the first place.

As a member of the EU, the UK is currently in the EU’s Customs Union and Single Market. The commonly known four freedoms of the Single Market allow goods, people, services and capital to move freely within it. For goods, this means the elimination of non-tariff barriers, including harmonisation of product rules and standards. Membership of the EU’s Customs Union removes internal tariffs between member countries and introduces a common external tariff for all non-member countries. The EU internal border is seamless, as goods are able to move freely between EU member states with no checks and no customs formalities. In fact, there is no EU customs border. However, even now, trading goods between EU member states requires certain procedures (for example, completing Intrastat reports for goods moved between EU member states).

Once the UK leaves the Single Market and the Customs Union, a new customs internal border will be introduced (or rather, an old customs border will be reinstated). Turkey – a country in a customs union with the EU – and Norway – a country in the Single Market but not a member of EU’s Customs Union – both have customs borders with the EU and related border formalities. Similarly, for the UK, once a border is introduced, a number of checks and procedures will become necessary. Of course, the practicalities of securing borders and dealing with customs procedures are a headache not isolated to the Brexit debate alone. Borders around the world come with formalities, friction and much political debate.

The friction caused by border formalities and customs checks is definitely not insurmountable. Countries around the world trade with each other despite what is often a high degree of friction at the border. Many UK companies currently trade with non-EU countries under the WTO rules – the same rules that will apply to trade with the EU under a no-deal scenario. However, the bottom line is that under any Brexit scenario that includes leaving the Customs Union and the Single Market there would be new and additional friction at the EU/UK border. This could lead to potential delays and would definitely lead to more paperwork and additional costs for traders – as a result of just having a customs border in place.

What actually happens when non-EU goods cross a UK border?

In order to understand the additional friction let’s look at what currently happens when a non-EU good arrives in the UK.

First of all, before non-EU goods arrive at the EU external border, a standard customs pre-notification needs to be submitted to the first place of entry into the customs territory of the EU. The deadlines for submitting a pre-notification depend on the mode of transport used. Pre-notification is one form of advance customs information about the imported goods which is used for risk analysis. Pre-notifications are made via an Entry Summary Declaration submitted to the EU Import Control Computer System (ICS). When the Entry Summary Declaration is submitted, a Movement Reference Number (MRN) is issued. Once the goods then arrive in the UK, the MRN is entered via a customs declaration into the Customs Handling of Import & Export Freight system (CHIEF) – the UK customs authority’s (HMRC) online computer system.

When non-EU goods arrive at the UK border, border procedures commence. A number of Government Departments and agencies are directly or indirectly involved in the process (e.g. Border Force, DEFRA and of course HMRC). The Border Force anti-smuggling and safety checks ensure that dangerous, prohibited or counterfeited goods are not smuggled into the country. Such checks are performed on a small percentage of imported goods – determined as a mix of random checks and risk-based criteria checks. These border checks are completed separately from customs procedures and are based on a different risk-assessment processes (and on IT systems that do not directly communicate with CHIEF). The Border force checks in Dover, for example, allow for information about the vehicle and the driver to be forwarded to the border authorities by the ferry company as part of risk analysis. While most vehicles pass through the checks, some can be asked for documentation or be subject to further inspection. Currently, after passing through these checks, EU goods that are not subject to any special customs procedure can continue onward.

When the pre-notified goods arrive in the UK, a notice of arrival is lodged by the carrier. The goods are to be accompanied by appropriate paperwork. This would include commercial and transport documentation, licenses and certificates that depend on the type of goods being imported, and transit documents for goods under transit procedure. Animal and food products need to comply with sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) requirements. Appropriate documents need to be provided and health and safety checks are carried out. While DEFRA has the overall responsibility for food safety and imports of animal and food products, local County Councils carry out SPS border checks on goods imported from outside the EU.

Finally, before third-country goods can be released at the border, they first need to be customs cleared. In the UK this is done via submitting a customs declaration to the CHIEF system. Goods coming from non-EU countries cannot be released from customs control without this customs clearance process (although there are some limited exceptions). In the simplest form, a customs declaration is a dataset of information about the goods which is submitted to customs authorities. The data collected includes: information about the type of goods; weight and commodity code; transport information; importer, exporter and customs broker; customs value and any special type of customs procedure the goods are entered into; as well as any applicable reliefs or customs duty suspensions. At this point, customs duties, import VAT and other taxes such as excise duties or anti-dumping duties are calculated. They can be paid directly to the customs authorities, but in the majority of cases the goods are released from the border without the payment being made, subject to a customs deferment account and related customs guarantee being in place. There are also occasional physical checks on imported goods. This involves, for example, checking that the goods have been correctly declared. Once the goods are customs cleared a removal note is issued by the customs authorities and the goods can be released from the controlled area at the border.

What are the sources of border friction?

The delays at the border resulting from anti-smuggling, documents and physical checks are the first and most obvious source of friction. The need for such checks post Brexit and the implications for supply chains and lead time have been discussed in detail elsewhere. The additional time required to conduct border checks on EU/UK goods post Brexit in combination with bottlenecks resulting from logistical and resource constraints at ports may lead to significant delays on both sides of the Channel. Issues such as lack of capacity, lack of appropriately trained staff, lack of appropriate infrastructure, and lack of space for lorries to queue and go through inspection are now well understood. Presently, for example, anti-smuggling checks are done on the French side of the Channel (for vehicles coming into the UK by train) due to the lack of inspection space on the UK side. New UK SPS checks will also be needed and a new check point will need to be created in ports such as Dover, where currently no such check points exist.

Having a customs border also leads to other, less obvious types of friction. For example, data needs to be collected, verified and entered into different systems. According to the World Customs Organisation, an average cross-border transaction involves up to 30 different parties and around 40 documents with about 200 data elements, most of which need to be re-entered to several systems. There will be additional time required behind the border to prepare and provide this data. A customs declaration has over 50 data elements. The importer collects most of this information and passes it to a customs broker or freight forwarder. A common belief is that each company has this information easily available. This is not necessarily the case. Goods need to be classified and a customs value needs to be established. This is done in accordance with strict international customs rules. Other data comes from various internal systems and teams. In all cases, data needs to be obtained, collected, maintained and updated, often by a dedicated team.

One could argue that some of these data fields for third-country customs declarations are currently needed for EU Intrastat reports. However, it is common knowledge that Intrastat reports are – to put it mildly – not completed with the same rigour as import customs declarations. Any issues with the quality of the data provided as part of an import declaration can lead to non-compliance and subsequent audits. The importer is legally liable for all the information submitted to the customs authorities and so has a responsibility to make sure it is correct.

Customs declarations are supported by commercial, transport and customs documentation. For some goods, licenses and certificates will need to be obtained. Depending what customs procedure the goods are entered into, the importer might be required to present or be able to provide other documents. In addition, goods imported under a trade agreement need to be accompanied by a proof of origin and goods imported under a customs union need to be accompanied by a proof of their customs status. Preparing these documents requires time and knowledge.

Customs declarations and related procedures thus lead to additional border friction and additional costs. Post Brexit, these costs will impact companies that are currently importing and exporting to third countries, as well as companies that presently trade only with EU countries, will only start to import/export after Brexit, and have thus never dealt with customs procedures. The costs related to new customs procedures include:

- Costs of complying with border procedures including customs clearance: for example, the fee paid to a customs broker or agent for submitting each declaration and the costs resulting from increased lead time;

- Operating model costs: costs of making the operating model compatible with the new border, adjusting physical and financial flows of goods, new special customs procedures introduced to mitigate the impact as well as any new licenses and certificates; and

- Internal customs compliance costs: running a customs compliance team, customs advice from brokers or consultants, or changes to the internal systems.

These costs will impact the businesses, and in the long term are likely to be passed onto the consumer by these businesses in order to protect their margins.

How will the UK border look like post Brexit?

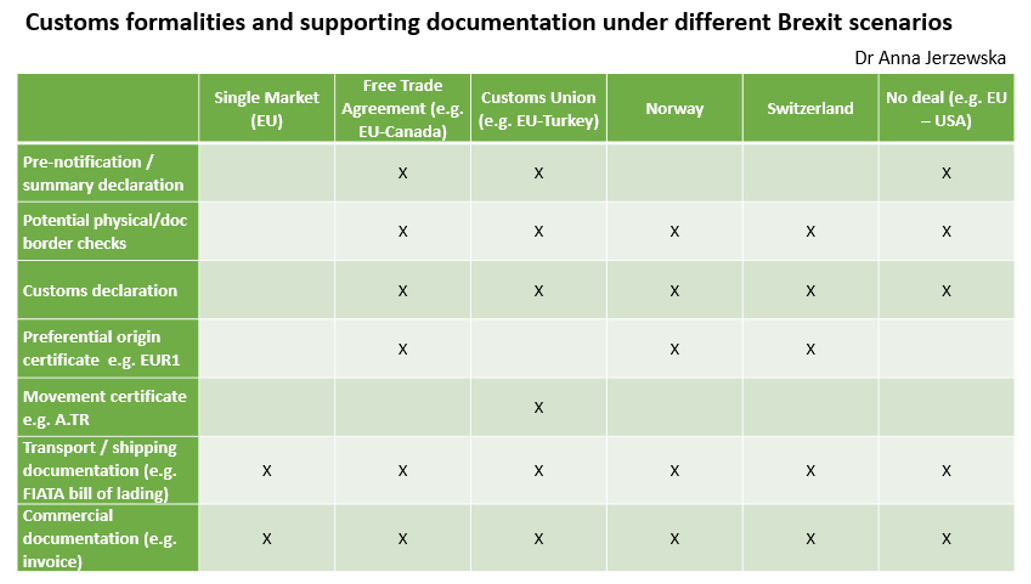

The Single Market with participation in the EU’s Customs Union is the only scenario that fully removes the need for customs procedures and a customs border. All other options currently require some form of customs clearance and document checks. The table below demonstrates the customs formalities that would be required under the different EU agreement scenarios that are regularly mentioned.

A pre-notification declaration is required in all cases apart from Norway and Switzerland. Norway and the EU, and Switzerland and the EU form a type of joint security area in terms of import risk assessment. Both sides remove the need for pre-notification for goods coming from the other country. Goods coming from third countries are pre-notified only in the first country and the results of risk analysis are passed to the customs authorities of the other, if the goods travel onward. These arrangements are as a result of bilateral agreements between these countries and the EU.

The UK and the EU could potentially reach a similar agreement. However, pre-notifications are a good way to collect information about the goods before they reach the border and are used to minimise and target physical checks. A customs declaration is used under every scenario. Even a full customs union doesn’t automatically remove the need for a customs clearance, and thus a customs declaration. The need for the customs declaration would depend on how the customs union is applied (e.g. harmonisation of all customs procedures or revenue apportionment). Some simplifications could be introduced – on the Norway/EU border, traders are able to submit import and export declarations at the same time without having to re-enter data and resubmit the documents to complete first the export and then the import procedure.

In addition, any non-WTO tariff (known as the most-favoured-nation tariff) under either a trade agreement or a customs union requires confirmation that the goods are eligible for such a “discount”. For each free trade agreement, this confirmation is based on the origin of goods, and the appropriate rule of origin outlined in the text of the agreement. Under a customs union, it is based on the status of the goods, i.e. whether the goods are in free circulation within the territory of the customs union. Companies wishing to benefit from the EU’s trade agreements need to provide a proof of origin – or in the case of importing goods to/from Turkey under a customs union – a “movement certificate” in the form of an A.TR document.

Could we move some of the customs procedures inland?

Customs declarations and border procedures are needed to collect tariffs and ensure that goods imported without tariffs – due to a free trade agreement or customs union being in place – meet the relevant criteria. However, customs declarations perform other functions as well. They assist customs authorities in applying various trade policy measures such as safeguards or anti-dumping duties, and are used to enter goods into special procedures. They also allow customs authorities to collect important information about the flow of goods in and out of the country.

One of the ideas that emerged right after the Brexit referendum was to move the customs border inland, either by moving the infrastructure inland or by changing when/where the customs declarations are submitted. Border checks and customs declarations currently take place in an area under customs authorities’ control – usually this is the border. Therefore, moving the checks inland would require either creating a system for extending this control or allowing the traders to take goods inland without that control by customs authorities. Under the existing EU customs legislation, there are options to submit a customs declaration after the goods have left the border.

First, there is an option to submit only a simplified customs declaration at the border. The procedure, called Customs Freight Simplified Procedure, allows the goods to be released from the border with only minimal information submitted electronically to the CHIEF system. At a later point, a supplementary declaration is submitted. The summary declaration contains full customs, fiscal and statistical information. This is still far from frictionless trade, but allows the goods to be realised from the border quicker and without the full customs declaration being immediately required. However, a company currently needs to obtain special authorisation from HMRC to use this form of customs clearance and needs to meet special conditions. The initial simplified declaration is still required.

Another option is the transit procedure. The Common Transit Convention was signed in 1987 and the procedure is used to move goods between the signatory countries, which include the EU, EFTA countries, Turkey, North Macedonia (FYROM) and Serbia. Common transit allows customs formalities to take place at the point of destination rather than at the point of entry into each customs territory (subject to a prior authorisation, transit procedure can start or end at company’s own premises). First, the goods are marked as in transit via the New Computerised Transit System (NCTS) and a Transit Accompanying Document (TAD) with a barcode is issued. The goods travel with the TAD document and the barcode is scanned when the goods arrive at each country’s border. A customs declaration is not required at the border and the goods continue to travel inland under the transit procedure. They are customs cleared at a customs office near the final destination. A company does not require a prior authorisation to operate common transit however, appropriate procedures need to be followed. Forms need to be submitted and a customs guarantee must be in place when the goods leave the border to secure the potential debt. These two procedures allow a country to move the bulk of customs clearance inland. Both of them, however, have a border element.

Some new innovations are being piloted too. The Norwegian customs authorities are currently running a pilot programme for further simplification of border procedures at one of their border crossings. First, a company needs to obtain an authorisation from customs authorities to be part of the pilot. It can then obtain a pre-approval on import and export documents. When the truck passes the border, the scanner picks up the license plate numbers and there is no need for the driver to stop. This is a way to streamline border procedures, which could in the future be expanded upon. However, a customs declaration still needs to be submitted to customs, and license plates still need to be scanned at the border, so the pilot does not remove the infrastructure at the border.

Conclusion

There are ways to move part of the border formalities inland, but in their current form they still require a border element. That could help to address delays in UK ports such as Dover, but this would not solve the Irish land border issue of avoiding all physical infrastructure at the border. Under any of the proposed Brexit scenarios, the UK will also be able to introduce unilateral simplifications of its own import customs procedures within the remit of international trade framework. It will not however, be able to influence what formalities are required by the EU and other countries. Therefore, imports from the UK will be subject to customs clearance requirements by the EU.

This seems to be the direction taken by HMRC when it comes to preparing for a no deal scenario and the recently published simplifications for importers. Importers would be able to provide minimal amount of information before the goods arrive at the border and defer submitting the full customs declaration. While there might be some relaxation in terms of physical and document border checks, these simplifications do not fully remove the need for customs formalities. For exports to the EU, UK traders would need to follow existing EU procedures.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of LSE Brexit, nor of the London School of Economics.

Dr Anna Jerzewska is a former big 4 customs adviser, currently she is a trade policy consultant at British Chambers of Commerce and the International Trade Centre in Geneva. For her other publications please see: www.freetradeagreements.co.uk/publications