Are referendums a sign of no confidence in the government? In this blog, Joseph Ward (University of Birmingham) compares the 1979 devolution and 2016 EU referendums in Britain. He argues that the 1979 Scottish referendum holds many important insights for understanding the political ramifications of the Brexit vote.

Are referendums a sign of no confidence in the government? In this blog, Joseph Ward (University of Birmingham) compares the 1979 devolution and 2016 EU referendums in Britain. He argues that the 1979 Scottish referendum holds many important insights for understanding the political ramifications of the Brexit vote.

Throughout the protracted debate on Britain’s exit from the European Union, many scholars and commentators have offered explanations and potential solutions to the dilemmas currently faced by the government. Quite unlike the ever-changing cast of characters in Theresa May’s Cabinet, one constant in this debate has been the ambiguity surrounding the British Constitution. As famously pronounced by legal scholar John Griffith, ‘Everything that happens is constitutional. And if nothing happened that would be constitutional also’.

The plasticity of the constitution – a great source of stability for so long – goes some way to explaining how the 2016 referendum could come about and why Britain’s institutions are crumbling in the face of the outcome. In a recent column Vernon Bogdanor suggested the best solution to protect the integrity of the United Kingdom would be to finally formalise the constitution, thus providing protection to reforms such as devolution and the Good Friday Agreement which seem unlikely to withstand the strain imposed by the Brexit result.

The extent of the political crisis that has engulfed the UK has led many to seek out comparable episodes from Britain’s history. In this vein, a recent Economist article considered several significant foreign and economic policy catastrophes such as Suez and the IMF loan crisis in 1976. It might be argued that such episodes, indicative of long-term decline, were subject to the whitewashing of British history successfully coordinated by Leave campaigners in lead up to 2016 and since.

However, whilst the origins of the Brexit debacle are rooted in the wider debate about Britain’s role in the world, in many ways that discussion has been superseded by the domestic ramifications of the vote. As noted in the same article:

‘…whereas the IMF crisis was limited to economic management, the current one extends to the unity of the British state. The four nations voted differently in the referendum, with England and Wales voting to leave and Northern Ireland and Scotland to stay’.

Not only has the aftermath of the 2016 referendum revealed divisions between the urban and the rural, between the young and the old, between those who’ve benefitted from higher education and those who haven’t, it has also brought the territorial composition of the United Kingdom back to the very centre of British politics. Once again, the historical compromise which forms the basis of the British state has created several seemingly insurmountable governing obstacles. In the case of Theresa May’s administration, perhaps the clearest such example is the Irish question, with the greatest number of objections to the negotiated deal centring on the so-called Irish backstop.

1979 and 2016: a useful comparison?

Whilst crises of either domestic or external origin never occur in a vacuum, the territorial dimension of the current predicament lends itself to historical surveys focused on domestic crises of a similar nature. With territorial and constitutional factors in mind, the initial devolution votes held by the Callaghan government in 1979 offer an interesting case for comparison. Although the obvious historical precedent, indeed the prior democratic mandate for 2016, is the 1975 European Communities vote, in terms of the result it was ultimately a success for the government, with Harold Wilson securing a two-thirds majority for continued membership.

The 1979 devolution votes under Callaghan, on the other hand, present one of only two other cases – including 2016 – of British government failure to secure the advocated outcome in a referendum[1]. Although often lost in the malaise surrounding the infamous Winter of Discontent, Callaghan’s inability to secure results in these two votes led to the downfall of his government, the repeal of the devolution legislation, and the inauguration of 18 years of Conservative dominance.

A comparison of these cases reveals two specific points of interest.

First, both cases highlight the primary role of party politics in debates over constitutional reform in Britain. The failed vote of confidence in Theresa May as Conservative leader coordinated by the European Research Group (ERG) – which only 6 weeks hence feels like a footnote – serves as a reminder that it was these same Eurosceptic pressures within the Tory party that forced Cameron’s referendum decision. The context of a hung Parliament, and the weakened position of Cameron in Coalition emboldened Eurosceptic demands and parliamentary pressure until he conceded.

In 1979, the growing electoral threat of the SNP between the two 1974 elections forced Labour’s hand in adopting policies on devolution. In the event this did little to quell SNP support, and in October Labour was returned with a majority of just 3 seats. This weak position, which eventually became a minority government, dictated that Callaghan was even more exposed to backbench pressures. In order to get the devolution legislation through, therefore, the government had to concede a number of amendments, most significant of which stipulated for a referendum to be held in each country to test support for the measures. Whilst Cameron ultimately seized the initiative from backbenchers where Callaghan could not, neither leader desired to hold a vote where party pressures forced them into doing so. This factor also applies, of course, to the Labour party divisions that precipitated the 1975 vote.

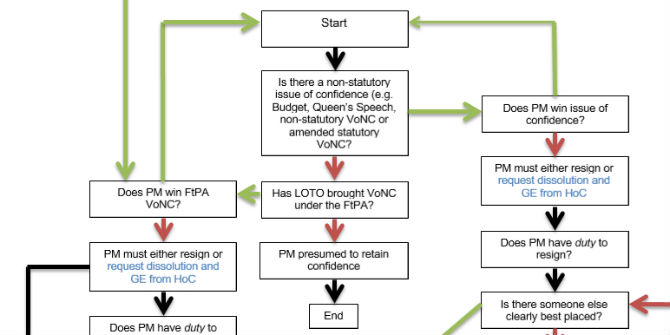

Second, after failing to secure the necessary support in either the Scottish or Welsh votes[2], Callaghan had to consider repealing the devolution legislation in accordance with the referendum amendment. This prospect prompted the SNP to remove support from the administration, which led to the tabling of confidence motion by the Conservatives in opposition. The motion went against Callaghan by one vote, triggering a general election that May, and ultimately the inauguration of 18 years of Conservative rule. Prior to that recently tabled by Jeremy Corbyn, this was the last occasion in which an opposition had tabled a confidence motion in the government, with or without success.

This eventuated in a scenario whereby anti-devolution Labour MPs under Callaghan could be charged with preferring ‘Margaret Thatcher in Downing Street to a Scottish Assembly in Edinburgh’. It has been suggested that party political arrangements that have dominated post-war British politics might be another casualty of the current crisis, and of course it might yet come to pass that one faction or another of May’s Conservative Party breaks ranks. Whilst the broader context of each case is one of political instability, this clearly shows the potential for failed referendum votes to present an existential threat to any incumbent administration, and to threaten the wider institutional arrangements of the British political system.

Moreover, 1979 holds another important insight for the narrative surrounding the history of the referendum in Britain. Studies which have analysed referendum use in the UK have tended to suggest that although the device has often been at the mercy of political expediency, it has also provided a ‘rubber life raft’, as Callaghan famously termed it, that parties have come to rely on when faced with party-splitting issues. However, it is important to note that referendums also have a history of exacerbating issues for British governments as well as offering solutions. Though it might be the case, as some have argued, that the only way out of the current impasse is to return to the people with a more concrete proposition, this should be treated with caution given the way in which party politics has previously dominated referendum practice. As Callaghan would discover, and May is still discovering, unfortunately that ‘rubber life raft’ doesn’t always lead to the shore.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE. Image C00 Public Domain.

Joseph Ward is a Doctoral Researcher and Graduate Teaching Assistant in POLSIS at the University of Birmingham.

Really engaging, giving a long term perspective to what can feel like a precedent.