What socio-economic characteristics were associated with a Leave vote? Leonardo S. Alaimo (far left) and Luigi M. Solivetti (Sapienza University of Rome) use Local Government District data and find that voters with GCSE-level education, and manufacturing workers in particular, were most likely to support Brexit.

What socio-economic characteristics were associated with a Leave vote? Leonardo S. Alaimo (far left) and Luigi M. Solivetti (Sapienza University of Rome) use Local Government District data and find that voters with GCSE-level education, and manufacturing workers in particular, were most likely to support Brexit.

Uncertainties still remain about what drove the Leave vote in the EU referendum. Our research set out to test these points:

- Were voters in the EU referendum swayed by the view of the party they normally supported? What was the effect of the Conservatives’ internal split on their followers’ votes? Did the party’s official line prevail despite some of the Cabinet recommending Leave? And what effect did Labour’s rather half-hearted recommendation to Remain have?

- Supranational integration – which the EU enables through freedom of movement – favours people with higher skills and incomes. Unsurprisingly, therefore, they are likely to support it. Those with lower skills and incomes might be expected to be indifferent to, or even suspicious of supranational integration. Do referendum voting patterns confirm this hypothesis?

- Better-educated people are more inclined to vote in favour of supranational integration. Is this the result of better education, or the higher income associated with it? And which level of education makes the difference – tertiary, higher secondary, or another?

- Hostility to immigration seems to have affected the outcome of referendums on EU membership. However, this hostility and the vote itself could be associated with either the size of the local immigrant population or the presence of groups structurally hostile to immigrants. (We note that in the UK slightly over half of manufacturing workers want few or no immigrants of a different race or ethnic group; managers, too, are unenthusiastic about immigrants (33%) (European Social Survey 2016).

Our analysis of Brexit was based on macro data regarding votes and characteristics of British Local Government Districts (LGDs). The share of votes for Leave in each LGD was the variable studied, while a set of political, demographic and socio-economic variables, as well as the political parties’ votes in the 2014 European elections, represented our explanatory variables. All the variables came from official sources and concerned the 380 LGDs: due to lack of data, however, we excluded Gibraltar and the Isles of Scilly from our analysis and treated Northern Ireland as a single district. We also excluded the City of London because some of its features (such as income) are off the charts.

Our statistical analysis was based on Pearson correlations, and regression models with robust error estimation. We used a fractional logit regression model: this model, developed by Papke and Wooldridge (1996), does not have the limits of the linear one and ensures all the fitted values remain within the range 0, 1.

Figure 1 shows the heatmap of the Pearson correlation coefficients (see the interactive graph).

Figure 1. Brexit vote: Heat map of Pearson correlations ( (darker blue = closer positive correlation; darker red = closer negative correlation)

- Of all the parties, 2014 votes for UKIP show the closest correlation with Leave; the Green Party is correlated with Remain, and the BNP with Leave. The previous votes for the Tories are non-significant as to the referendum outcome; Labour’s votes show a weak negative correlation with Leave.

- Variables measuring ageing correlate positively with Leave. In other words, older people are more likely to have voted for Brexit.

- Income is correlated negatively with Leave, while the latter’s associations with unemployment, workless households, and benefit claimants (ie variables measuring economic disadvantage) are always positive, but weak.

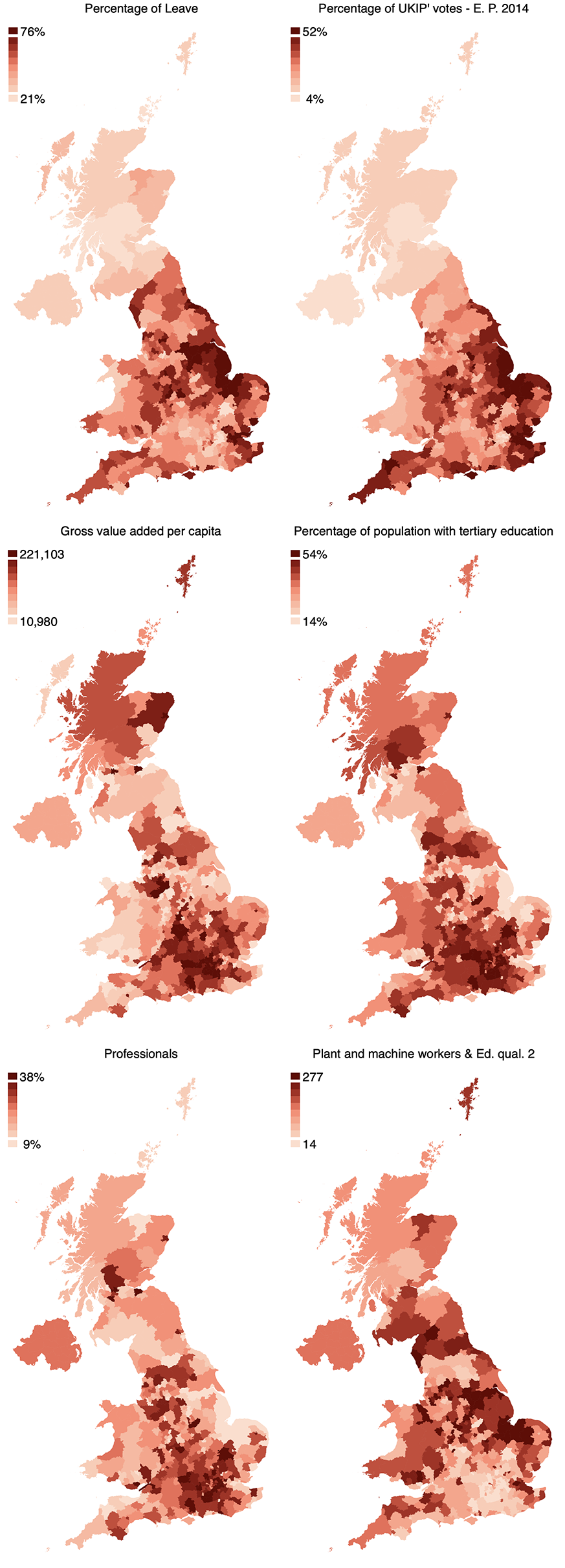

- All the most skilled professions are associated negatively with Leave, whereas all the middle and lower-class occupations are associated positively with it. However, the degrees of correlation are different, and manufacturing workers represent the occupation with by far the closest positive association with Leave.

- Graduates are closely and negatively correlated with Leave; all the other educational levels, from no educational qualification to level 3 (A-levels), are positively correlated with it. Qualification level 2 (GCSEs) shows the closest correlation. Some interactions of educational qualifications with occupations increase the degree of correlation. For example, level 2 times manufacturing workers emerges as one of the best predictors of Leave.

- The associations of both immigrant stock and inflow with Leave are close and negative; on the other hand, the association of immigrant inflow variation with Leave is positive.

The results obtained by means of regression models suggest the following conclusions:

- Partisanship played a part in the Brexit vote. Where there was no internal split in a party over whether to Remain or Leave, the association between the party’s previous votes and the referendum results was strikingly close, as in the case of UKIP. Instead, the impact of Conservative votes was limited, most probably due to the party’s internal split. However, Labour’s lukewarm support for Remain seems to have been at least as detrimental to the Remain cause as the Conservatives’ internal split.

- Richer areas are more inclined to vote for supranational integration. Similarly, better-off and highly skilled people (eg professionals) were associated with Remain. However, the relationship between the worst socio-economic conditions (unemployment, workless households, and benefit claimants) and Leave votes was surprisingly weak. Instead, Leave was closely associated with the presence of people working in manufacturing, skilled tradespeople, and those with apprenticeship qualifications. Concurrently, the association between Leave and managers emerged as significant and positive. The largest contribution to Leave did not come from areas characterised by the lowest level of education but from those with GCSEs. Ultimately, the vote for Leave was more socially distinctive than expected.

- The impact of higher education was more powerful than that of income and highly-skilled workers. This finding suggests that higher education confers a preference for supranational integration – probably of cultural origin – which does not come from simply earning more or acquiring skills.

- Lastly, the presence of immigrants locally was not such a crucial factor as expected. But the group who were most likely to have voted Leave – manufacturing workers – are those most hostile to immigrants and often share an in-group identity and a certain amount of unity. This suggests that anti-immigrant attitudes may come from cultural and social attitudes rather than the experience of living near migrants.

Figure 2. Brexit vote: maps of the UK’s Local Government Districts, showing Leave votes (%), UKIP votes in the 2014 European elections (%), gross value added per capita (£), population with tertiary education (%), presence of professionals (%) and interaction of educational qualification 2 (GCSE %) and manufacturing workers (%)

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE. It is based on L.S. Alaimo, L.M. Solivetti. 2019, “Territorial determinants of the Brexit vote.” Social Indicators Research.

Leonardo S Alaimo is a PhD candidate in the Department of Applied Social Sciences, Università di Roma Sapienza.

Luigi M Solivetti is a Professor of Sociology at the Università di Roma Sapienza.

Would definitely have to agree, UK manufacturing has lost a fair amount of work due to strength of the pound compared to the under valued Euro.