The Northern Irish backstop proposal is complex – but it is not unprecedented, writes Thea Don-Siemion (LSE). The Treaty of Versailles established arrangements to prevent a hard border between Germany and Poland in Silesia. It failed, becoming a flashpoint in the relationship between the two countries. Even a permanent backstop is a poorer guarantor of peace in Northern Ireland than remaining in the EU.

The Northern Irish backstop proposal is complex – but it is not unprecedented, writes Thea Don-Siemion (LSE). The Treaty of Versailles established arrangements to prevent a hard border between Germany and Poland in Silesia. It failed, becoming a flashpoint in the relationship between the two countries. Even a permanent backstop is a poorer guarantor of peace in Northern Ireland than remaining in the EU.

With her withdrawal agreement crushed in Parliament, Theresa May went to Brussels to demand a time limit on the contentious Irish customs backstop intended to avoid a hard border on the island of Ireland. The EU poured cold water on the Prime Minister’s request, holding firm to its position that a time-limited backstop would be a “complex and unprecedented arrangement”, and thus unworkable.

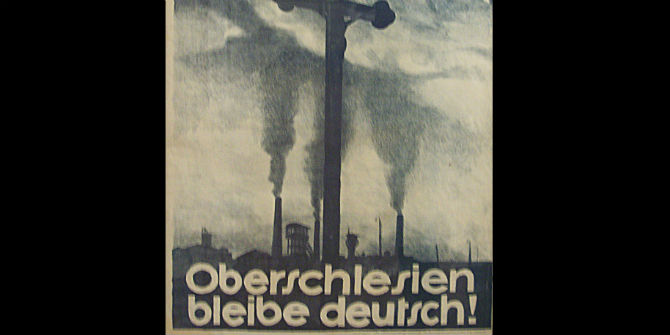

Theresa May’s proposal is certainly complex, and it may be unworkable. What it is not, however, is unprecedented. Modern European history holds at least one close historical parallel to the Irish backstop: the arrangements under the Treaty of Versailles of 1919 to prevent a hard border between Germany and Poland in the Upper Silesian industrial region. The implications of this episode for the prospects of May’s proposed arrangement are not encouraging. The ‘Silesian backstop’ was intended to provide a grace period during which Poland and Germany could negotiate a permanent agreement regulating cross-border trade in Upper Silesia. Instead, it resulted in no deal, inflamed ethnic tensions and sparked a ruinous tariff war. Far from promoting Polish-German reconciliation, it added kindling to the fire that was to erupt in the second world war.

Upper Silesia in the wake of the first world war bears many parallels with Northern Ireland today. Ruled by the Polish crown in the Middle Ages, the region had over the centuries become subject to German settlement and rule, a process which reached its height after the partitions of Poland in the late 18th century. Sitting atop one of Europe’s great coal deposits, the region developed during the 1800s into Germany’s second great centre for heavy industry. German capital and (chiefly Protestant) German migrants became enmeshed in a Polish (chiefly Catholic) rural economy, heavily interdependent and without a clear ethnographic border between the two communities.

When Poland regained its independence in 1918, the question of how to divide Upper Silesia between Poland and Germany became a pressing matter on the agenda of the Versailles peace conference. Any conceivable border in the densely populated region would sever supply and production chains, separate workers from their places of employment, and even cut across mine galleries deep underground, making resources liable for tariffs before they even reached the pit-head.

The participants in the Versailles peace conference recognised the magnitude of economic harm and potential for political turmoil that would result from a hard border in Upper Silesia. They worked out a compromise between the positions of Germany and Poland, both of which wanted the full industrial region in a union with themselves. The question of where to draw the border between Poland and Germany would be settled by plebiscite, and the final economic settlement left to a trade treaty negotiated between Poland and Germany. As neither of these actions could be implemented immediately, the Treaty of Versailles required Poland to “permit… the exportation to Germany of the products of the mines in any part of Upper Silesia transferred to Poland… free from all export duties or other charges or restrictions on exportation”. A subsequent convention modified the terms: the ‘Silesian backstop’ would henceforth expire earlier, at the end of June 1925, but would cover the full range of industrial goods produced in the part of Upper Silesia under Polish sovereignty. To prevent abuses of the backstop provisions, Poland consented to an internal customs frontier between its part of Upper Silesia and the remainder of the country, and a measure of parliamentary and fiscal devolution to the Province of Upper Silesia.

The high hopes at Versailles that the compromises brokered on Upper Silesia would be respected by both parties and would serve as a foundation for stable relations between Poland and Germany quickly proved misplaced. Far from conciliating the two countries, the division of Upper Silesia sparked intense violence, as nationalists on both sides jostled to maximise their gains at the expense of the other. Though the backstop was intended to facilitate negotiations, its time-limited nature intensified the conflict as partisans on both sides sought to insure themselves against the fallout of ‘no deal’. Hostilities swiftly broke out. Less than two months after the Treaty was signed in June 1919, the Polish population staged an uprising in order to force a revision of the settlement in Poland’s favour. Though this uprising was quickly crushed by German Freikorps paramilitaries, it was followed by two further outbreaks of violence.

The Silesian uprisings, and the repressions that followed them, forced the revision of the plebiscite held in 1921 and undermined the democratic legitimacy of the Upper Silesian peace process. Nor was the damage confined to Upper Silesia: the violence proved corrosive to political stability in both Warsaw and Berlin. On the German side, the reliance on paramilitaries to suppress the Polish risings cemented the place of the anti-system far right within the mainstream of the Weimar Republic’s politics. In Poland, Marshal Józef Piłsudski used the accusation of being ‘soft on Silesia’ to force the resignation of a democratically elected government in June 1922, ushering in a year and a half of political chaos and paving the way for his eventual coup d’état. In both countries, the decision to provide material support to a side in the conflict led to fiscal overreach and contributed to the emergence of hyperinflation.

Under such inflamed circumstances, attempts to negotiate a permanent trade agreement between Poland and Germany were doomed. As the end date of the backstop neared, the German side, which hoped to use Poland’s dependence on Germany as a market for its exports to force Poland to revise its borders in Silesia and the hated ‘corridor’ in its favour, engaged in a campaign of stalling and stonewalling in an attempt to ‘run down the clock’. When the German side finally came to the table, only a few months before the deadline, the gap between the Polish and German positions was too vast to be bridged. Both sides, especially Germany with its greater economic leverage, engaged in brinkmanship, upping the stakes of the negotiations to induce the other side to fold. Finally, the Germans imposed a quota on Polish coal that amounted to a de facto embargo; the Poles retaliated in kind. The backstop lapsed without a deal being reached.

Poland and Germany remained at economic loggerheads to the last days of the Weimar Republic. The bitter relations resulting from the failure of the Silesian backstop cast a shadow over European stability in the later 1920s. The rights of Polish and German minorities on opposite sides of the Silesian border became a dominant presence on the agenda of the League of Nations in Geneva. Even when the economic strains of the Great Depression brought Polish and German commercial delegations together again, a resolution proved elusive. While the two parties were able with great effort to conclude a trade agreement— better than no deal, but much more limited than the provisions of the ‘backstop’— the treaty met with a hostile response in the Reichstag, galvanising nationalist and Nazi opposition to the ‘compromised’ Weimar system. It was never ratified. Ironically, it took the dictatorial initiative of Adolf Hitler, whose rise owed much to the animosities unleashed by the Silesian conflict, to bring the Polish-German trade war to an end.

The experience of the Silesian backstop in the troubled period after the First World War has unsettling implications for the proposed Irish backstop in the troubled period after the global financial crisis and Brexit. If history can teach us anything about current events, it is that Theresa May’s proposal for a time-limited Irish backstop, whatever its attractions in terms of maintaining the unity of the Conservative Party, is doubly dangerous and should be resisted by the EU. The Silesian backstop of 1919-1925 did not prevent a no-deal outcome, but only delayed it. Worse, because no deal remained on the table, the time limit on the backstop fanned the flames of the inter-ethnic strife by incentivising both sides to secure for themselves a position of strength in time to influence the final settlement.

The lessons of the history of Europe between the two wars have already been learnt once before. The signatories of the Treaty of Versailles vested their hopes for peace in a system of national self-determination, state sovereignty, controlled immigration with unenforceable minority treaties to protect nationals caught on the wrong side, and a commitment to free trade in theory that gave way to protectionism once the hard choices of structural change became apparent. The combination proved explosive. When their successors, at the end of a second ruinous war, once again confronted the problem of another highly interdependent industrial region split by national borders and ethnic divisions, they did not put their faith in backstops. Rather, they founded the European Coal and Steel Community, which became the European Union. One lesson from the Silesian backstop is that a time-limited backstop in Ireland has all the markings of a dangerous chimera. A stronger lesson is that even a permanent backstop is a poorer guarantor of peace and prosperity in Northern Ireland than remaining in the EU.

This post represents the view of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE.

Thea Don-Siemion is a PhD student in the Department of Economic History at the LSE.

What an interesting parallel, thank you.

This confirms my growing feeling that the withdrawal agreement and the backstop just cannot be accepted and the UK will have to take its chances on no deal. Fortunately I don’t think hard borders have to be as hard as they were 100 years ago, because most goods cross in shipping containers with an identifying code, meaning that customs declarations can be done with computer bits and bytes rather than piles of paper documentation.

I don’t want to minimise the problems, especially on the Irish border. I am sorry for all those affected. If the DUP continue to insist that there be no new controls between the UK and Northern Ireland, then that has to be respected, until the Northern Irish elect other representatives to Westminster, or elect a functioning government to Stormont. For me the only reasonable remaining alternative to no deal is for the UK Government to overrule the 2016 referendum and revoke Article 50. But if life outside the EU is really so bad as some Remainers say (I don’t think anyone knows), it would be better for the UK to experience it and then apply to rejoin, since at least that would move the democratic debate in the UK on.

Instead of Silesia could a better comparison be that of the Saarland from 1920 onwards? Politics aside, hopefully, and focusing only on the integration with the incumbent power.

Superb article

Superb article about something I never knew about. In spite of the defeat of WWI it seems – and is strongly implied by the author – that the more powerful state is already fighting back.

Could Jack Sparrow expand a bit, perhaps give us a link if you have a good one?

The whole history of Prussian engagement in Poland does indeed have uncanny parallels with England in Ireland. Danzig was the „Alternative Arrangement“?

Excellent article. Some of the parallels are worrying. The return to conflict in Ireland is a real possibility unless the matter is sorted out. Post January 1933 was the turning point for Poland/Germany and indeed, the world. The current situation in the UK can be likened to the Wiemar Republic, or at least, it’s early road to destruction. The prospect of a sharp turn to the Right and an ineffectual, divided opposition is a a clear warning sign. We learn from history… or should.