The 2019 European Parliament elections are now over. While the final results have not been published for all EU countries and the precise membership of the European political groups may still evolve, the outcome of the elections have confirmed the key expectations discussed in our previous blog post. In particular, as many commentators pointed out after the elections, the new European Parliament will be more diverse than the previous one. One question has however not been addressed so far: would the situation change after Brexit? Brexit would, in fact, imply important changes for the European Parliament, as it would reduce its size and alter the composition of its political groups. In this post, Thierry Chopin, Nicolò Fraccaroli, Alessandro Giovannini, Nils Hernborg and Jean-Francois Jamet describe what the European Parliament would look like post-Brexit and which political implications would derive from its new composition.

Until the UK’s withdrawal becomes legally effective, the number of seats will remain at 751, which is the maximum number allowed by the EU treaties. The number of MEPs per country will remain fixed and nothing will change compared to the previous legislative term. After the UK’s withdrawal from the EU comes into force, the new rules that were formally adopted by EU leaders at their summit in Brussels on 28-29 June 2018 (and agreed by the European Parliament) will come into force.

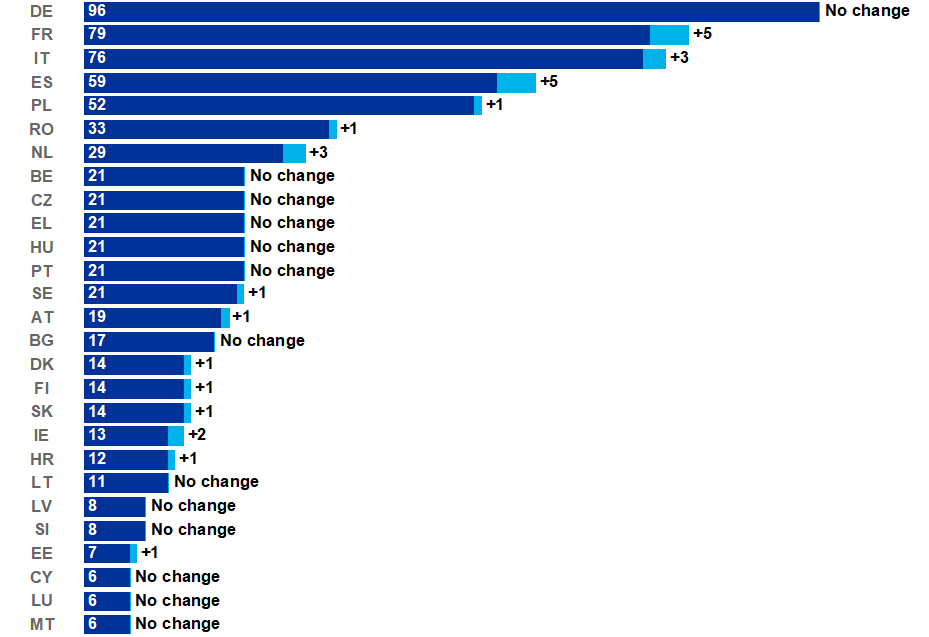

Accordingly, 73 MEPs elected in the UK will leave the European Parliament and the number of total seats will be reduced to 705. Out of the 73 UK’s seats, 46 seats will be kept for future EU enlargements, while 27 will be redistributed to some EU countries. While no country will lose any seat, some will gain new seats (e.g. France), unlike others (e.g. Germany), as shown in the chart below. Within each country, the redistribution of seats among political parties will take place based on the electoral results. This implies that Member States like France, Italy or Spain (which together will gain 13 of the 27 reallocated seats, see chart below) have put, for the time being, the election of these additional MEPs on hold, in a “reserve list”: accordingly, the election of the additional representatives will be done based on the election results, but they will enter in the European Parliament only at the time of Brexit.

Figure 1 – Planned reallocation of 27 seats in the European Parliament after Brexit

By altering the composition of the European Parliament, Brexit will also impact on the relative strength of political groups in the European Parliament, as our previous post based on opinion polls suggested. Using the provisional results available, it is now possible to foresee with more accuracy what the European Parliament would look like after Brexit. To estimate the seat composition in the post-Brexit scenario, we use the new seat allocation quotas per country and allocate the additional seats using the largest remainder method and assuming a single constituency with a proportional electoral system for each Member State. In a nutshell, we rank the size of the remainders after allocating the original seats and subsequently give the additional seats to the parties with the largest remainders. Since all countries do not have single constituencies with proportional electoral systems (e.g. Ireland), and may also apply other methodologies for allocating marginal seats, this method is not perfect but should give us a very good estimation on the allocation of additional seats.

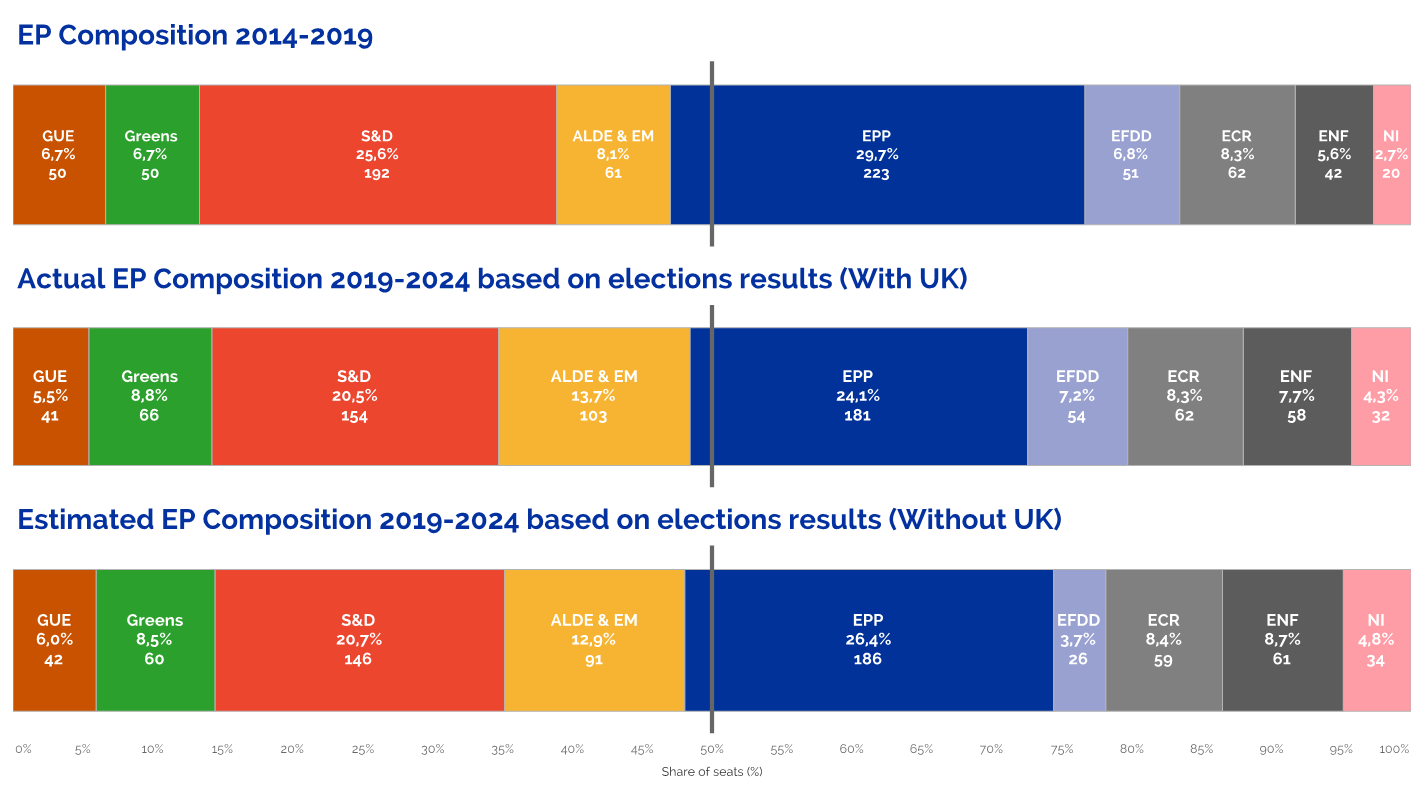

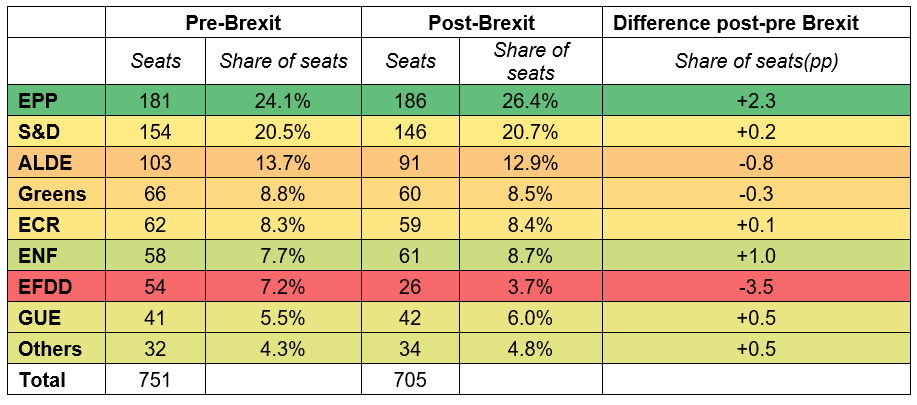

The impact on the composition of some of the political groups will be significant. The EFDD group would lose 29 MEPs from the Brexit Party, but gain 1 thanks to the election of an MEP in Italy from the 5 Star Movement. In a similar vein, the liberal ALDE+ group would lose 16 UK members, but gain 4 thanks to new members being elected in France, Ireland, Netherlands and Spain. The Greens would lose 11 UK delegates, but gain new 5 MEPs from Austria, France, Netherlands, Spain, and Sweden. The S&D would lose, instead, 10 UK MEPs, but gain 2 new members elected in France and Romania. Finally, the group of the Conservatives, ECR, would lose 4 UK delegates, but gain 1 MEP from Croatia, whereas the left-wing GUE would lose 1 UK delegate, but gain 2 MEPs from Denmark and Ireland. As no EPP MEP have been elected in UK, the centre-right group would gain 5 seats thanks to the election of news members in Finland, France, Italy, Poland and Slovakia after Brexit.

Figure 2 – European Parliament Composition

All in all, the share of pro-EU groups (EPP, S&D, ALDE, Greens) would slightly increase from 67.1% to 68.5%. This result confirms that the new European Parliament will be more fragmented independently of Brexit as expected in our previous post: a post-Brexit majority in support of the European Commission will, in fact, continue to require ALDE and/or the Greens to join the EPP and S&D. The ranking of parties, and therefore their bargaining power on legislation, will however change. Ceteris paribus (i.e. without considering possible reshuffling of political groups), after Brexit the Greens would become the 5th group (down from 4th) and ENF the 4th (from 6th), with Greens, ENF and ECR holding a similar number of seats. The EPP group would be the main beneficiary post-Brexit (+2.3 percentage points). It is thus possible that some groups would ask to re-shuffle the allocation of Committee’s Chairmanships to better reflect the new share of seats each groups would hold within the European Parliament post-Brexit. This may also be reflected in the Committees’ composition, hence in the way speaking time/dossiers are allocated among political groups.

Figure 3 – European Parliament composition in the pre/post Brexit scenario

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of the institutions with which they are affiliated, the Brexit blog, nor the LSE. Image by European Parliament, Some rights reserved.

Thierry Chopin is the author of several books and articles on European integration. He holds a PhD in Political Science from the School for Advanced Studies in Social Sciences (EHESS). He is Professor of Political Science at the Catholic University of Lille (ESPOL, European School of Political and Social Science) and Visiting Professor at the College of Europe (Bruges). He is special advisor at the Jacques Delors Institute.

Nicolò Fraccaroli is a PhD candidate in Economics at the University of Rome Tor Vergata. He holds a MSc in Political Economy of Europe from the London School of Economics and a bachelor in Political Science from LUISS Guido Carli (Rome). He is co-author with Robert Skidelsky of the book Austerity vs Stimulus. The Political Future of Economic Recovery (Palgrave Macmillan, 2017).

Alessandro Giovannini is the author of several articles on European integration, focusing mainly on political economy issues. He graduated from the London School of Economics, Sciences Po and Roma Tor Vergata University. He worked in several European think thanks: Centre for European Policy Studies (CEPS) in Brussels, the Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI) in Rome and the Observatoire Français des Conjonctures Economiques (OFCE) in Paris.

Nils Hernborg is currently a Master student in International Economic Policy at Paris School of International Affairs, Sciences Po. Prior to pursuing his master, he worked as data analyst in the fintech industry. He also holds a BSc in Political Economy from King’s College London.

Jean-Francois Jamet is the author of several books and articles on European integration and the Economic and Monetary Union. He studied Economics at the Ecole Normale Supérieure (Paris School of Economics) and Harvard University, and Political Science at Sciences Po. He has worked for the World Bank and the European Commission.

Thank you for an interesting blog post.

However, there is one mistake in it: The Finnish “brexit seat” will not go to an EPP candidate but a green one.

https://vaalit.yle.fi/epv2019/en/candidates

https://www.thenewfederalist.eu/finland-centre-right-wins-european-elections-but-candidates-for-eu-top