The Conservatives and Labour performed unusually badly in the recent European Parliament elections, while the Lib Dems, the Brexit Party and the Greens did well. What might the result – and recent local elections – tell us about the outcome of a future general election? Ben Farrer (Knox College) looks at whether second-order elections are, historically, a guide to a party’s performance in a GE.

The Conservatives and Labour performed unusually badly in the recent European Parliament elections, while the Lib Dems, the Brexit Party and the Greens did well. What might the result – and recent local elections – tell us about the outcome of a future general election? Ben Farrer (Knox College) looks at whether second-order elections are, historically, a guide to a party’s performance in a GE.

Introduction

Predicting elections is never easy, and Brexit has only made it harder. Across Europe, people are looking to the UK for clues about what will happen, but nobody really knows what clues they should be looking for. The recent byelection in Peterborough, the 2019 European Parliament elections, and the local council elections before that, might all carry useful hints about future trends. But they don’t all tell the same story. If there is a smoking gun then it’s still surrounded by smoke.

In a recent paper “Connecting Niche Party Vote Change in First- and Second-Order Elections”, I suggest one relatively simple way to cut through this uncertainty. It is the scientific version of the ‘brute force’ approach. Collect all the historical data – look at every potentially-informative election leading up to a general election – and see which ones are most closely correlated with subsequent general election results. After getting data from six countries and from three decades, it turns out that local council elections are much better than European Parliament elections as a guide to future general elections. This finding has important implications for how we sort through the clues in predicting the next UK general election.

Predicting first order (not in Star Wars) elections

I began this research because I was particularly interested in niche parties. These are parties that focus on one main issue that the party members believe is inadequately addressed by mainstream parties. A classic example would be the Green Party, focusing on environmentalism, but we could also consider the Brexit Party as an example, with their focus on leaving the EU.

These niche parties are usually newer, smaller, and less well-known than their competitors. They also tend to be less successful in general elections. Some scholars have argued that they can compensate for this by using other types of elections, like sub-national elections or European Parliament elections, to build their base. Sub-national and European Parliament elections are ‘second-order’ elections, generally perceived as less important. This means voters are more willing to take a chance on a niche party. If those parties can capitalise on this and do well in second-order elections, they might also be able to use it as a springboard for first-order success.

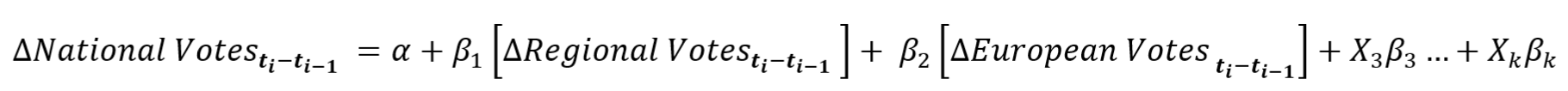

I tested this, beginning by splitting up countries into their electoral districts. For every district, the general election result was recorded, and then was matched up with the most recent European Parliament election, and also with the most recent sub-national (local or regional) election. Then things get complicated. With six different countries, it was also important to account for differences in electoral rules, differences in election timing, differences in turnout, and differences in the federal structure of the country. In the end, the best way to incorporate all this variation was to focus on one statistic: the correlation between the change in a niche party’s vote total between two second-order elections, and the change in their vote total between two general elections. This is explained further in the paper, but the basic idea was to find a way to account for growth in votes despite a lot of variation in turnout percentage. The main equation from the paper boils this down in a hopefully helpful way. If each electoral district in each country is labelled i and each iteration of an election is denoted t or t+1 then the analysis takes the following form:

Results

The results show that across most of these countries, it is the sub-national elections, rather than the European Parliament elections, that predict how niche parties will do in national elections. If we take the example of Germany, imagine that a niche party wins 2000 more votes in a regional election in time t+1 than they had at time t. The model then predicts they will gain 1731 votes in the next national election. If, on the other hand, they had instead won 2000 more votes in European Parliament elections, then the model predicts they will get only 86 more votes in the next national election.

So what does this mean for the UK? First, some caveats. No country has ever left the EU before. So we should be cautious about extrapolating from past results. Also, the article was written using data from different countries, not the UK. I did look at results from the UK, but only national-level data were available. The same patterns seemed to show up, but there wasn’t enough data to do a rigorous analysis. Still, despite those caveats, I think this research can be useful for understanding the UK’s current situation.

In the most recent local elections, the Lib Dems and the Greens increased their share of the vote. The Conservatives lost ground, as did Labour. The Brexit Party and Change UK were not competing yet. In the most recent European Parliament elections, the Brexit Party won the highest vote share, with the Liberal Democrats coming second, and Labour and the Greens following them. Change UK were not able to make much headway. If we look at the results in the light of the research described above, we should be treating the local results as ‘part signal, part noise’ and the European results as essentially ‘all noise’. So the Lib Dems and the Greens should expect to replicate their modest gains from the local results, not the dramatic swings of the European results. Change UK should not necessarily be too disheartened by their European showing, and neither should the Brexit party be too encouraged by their victory.

Perhaps there is still no smoking gun. By the next general election, the Conservatives will have a new leader, the Brexit process will probably produce some more of the crises left up its sleeves, and of course who knows what else will happen. But underneath it all, elections are still elections. Since the inception of the European Parliament, there has never been a consistent pattern of niche parties doing well in European elections and then going on to do just as well in national elections. Sure, just because something has never happened before doesn’t mean it won’t happen now, but the evidence is definitely against it. So as we predict what might happen next, it’s important to bear these findings in mind.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor LSE.

Ben Farrer is Assistant Professor of Environmental Studies at Knox College, USA.

Another point for the UK is that the EU elections are held under a PR system, while general elections are “first past the post”.

“First past the post” favours the two major parties in a basically two-party system, while minor parties are more fairly represented by a PR system. This creates the bizarre paradox that Nigel Farage’s Brexit Party wishes to do away with a form of election in which they do very well ( the European elections), and replace it with one in which they do very badly (UK general elections).