The latest EU Parliament elections offered a new milestone for assessing the efficiency of its institutional communication. In this blog, Jorge Tuñón and Uxía Carral (Carlos III) argue that the failures of EU’s communication efforts can be improved if it substantially reforms its institutional communication regarding the creation of a European public sphere, the identity crisis, multilingualism, Brexit, Euro-myths, and fake news. They analyse how European institutions have been speaking to the European population about these issues.

This investigation focuses on measuring the impact of the EU’s communication to audiences in three countries (Germany, United Kingdom and Spain). We argue it is fundamental to take into consideration the socio-political and economic frameworks, as well as the differentiating sense of belonging which citizens of each country show towards the European integration process. Additionally, the analysis of social networks uncovers new narratives that European institutions have been using to appeal the youngest audiences in order to combat populism and Euroscepticism.

There is no doubt that these days the EU has a duty to make its actions known across different mediums, and social media appears to be crucial in connecting political actors with society. This may be seen as part of the strategy of political communication of a supranational entity such as the EU. Our work highlights how the representative offices of the EU in Germany, United Kingdom and Spain use Twitter as their main platform to inform, communicate, involve and influence the opinions and the national public agendas of the Member States. We find that the Europhile or the Eurosceptic feelings that prevail in each country determinate the EU’s communication in these Member States. Furthermore, specific communication tendencies have been detected for each country regarding four aspects analysed (frequencies, functions, contents, and sources).

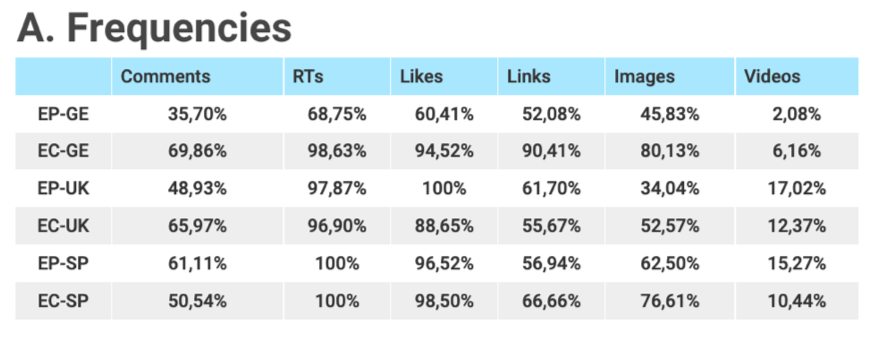

With regard to word frequencies, we show that the geographical and political distance with respect to the European decision-making processes incentivises the use of Twitter as a communication tool. Accordingly, the size of the sample for an identical period of time, as well as the number of followers shows that, firstly, the geographical distance (Spain) and then, the political one (UK) positively conditions the use of Twitter by the EU. We presume that a deeper analysis of the engagement data (comments, RTs and likes) would validate the hypothesis for both cases. In contrast, the percentage change of frequencies in the EU’s representative offices in Germany revealed a different management of their profiles. There is a higher number of interactions and of its own content in the Commission account than in the Parliament’s account.

Graphic 1 / Results from the frequencies for the cases of Berlin, London and Madrid EC an EP

Moreover, crossing the variables of frequencies (Graphic 1) and contents (Graphic 3), it can be claimed that, although the European Commission uses Twitter more frequently than the EU Parliament, the reach is quite similar due to limited differentiation between the message sent by each profile. The impact of these accounts on Twitter does not differ considerably due to the homogeneity of content and themes published by either the office of the Commission or the Parliament. Nevertheless, in terms of frequencies, we observe a superior use frequency for the Commission than the Parliament accounts in the three countries analysed.

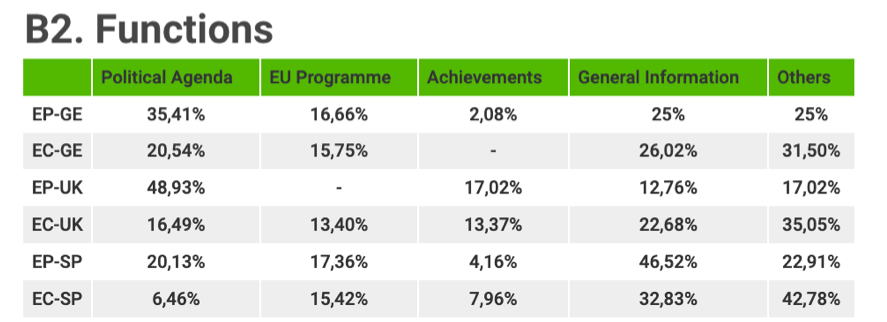

Graphic 2 / Results from the contents for the cases of Berlin, London and Madrid EC an EP

Furthermore, Euroscepticism determines the message regarding content and its function. Indeed, the discrepancies within the degree of Europeanisation, or the development of the Eurosceptic movement, have been revealed as determinants in each country. On the one hand, we found an exclusive theme concentration about the relationship between the EU and the Member State, and citizens, as well as a lack of attention to EU policies, in both accounts belonging to the EU institutions located in London. Those results were contrasted with the ones in Berlin and Madrid, which had more widespread thematic coverage and, concretely, a broader focus on EU policies, and less interest in EU politics and the EU as a political project.

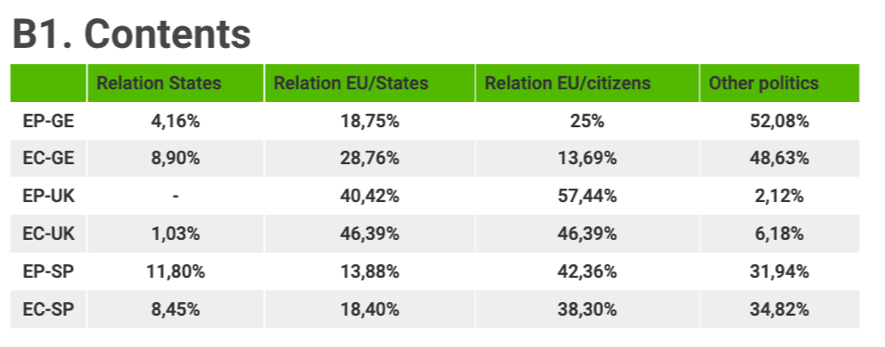

There is also a difference with regard to the achievements category at the functions level. In particular, it seems to be thought necessary for the institutional profiles in the UK to report about the EU’s achievements because of Brexit and the Eurosceptic climate. The EU delegation seeks to counteract misinformation and fake news. In contrast, the Berlin-based offices attribute the lack of emphasis on promoting the EU’s objectives to the faith in the European process among the German population. The Spanish entities share this approach, which is further explained by their geographical and political proximity to the European institutions and to European decision-making processes.

Graphic 3 / Results from the functions for the cases of Berlin, London and Madrid EC an EP

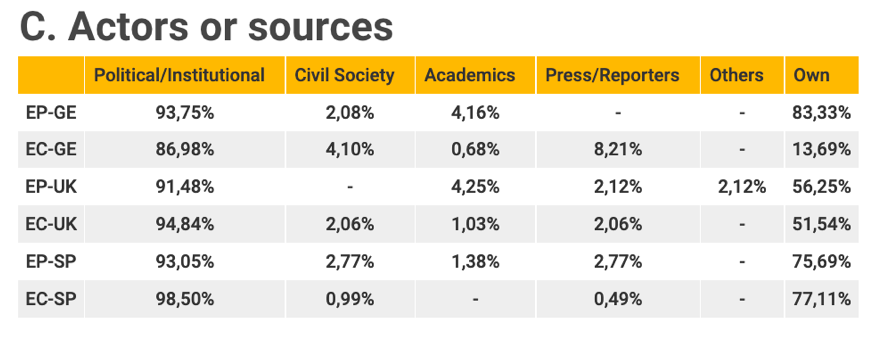

However, the EU’s information strategy is one-directional. It is aimed towards a limited audience comprised of political or institutional elites and does not involve other actors/stakeholders from any of the three states. Effectively, the involvement of any actor except the representatives of the EU institutions is practically nonexistent. Neither civil society associations, nor journalists or academics have had any involvement in the production, management, or dissemination of the information published via Twitter and targeted at the national audiences of the three countries.

Graphic 4 / Results from the actors for the cases of Berlin, London and Madrid EC and EP

Therefore, we find that the EU talks to itself and to its elites, but not to EU citizens en masse. The ‘European message’ sent out by the EU institutions in member states is unidirectional and does not represent or involve the variety of actors comprising European society. Political and institutional actors dominate the communication efforts of EU offices in Berlin, London and Madrid. There is a glaring lack of involvement of civil society, the academy or the press, among other stakeholders, in this process.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE. Image License: CC0 Public Domain.

This research is a part of two projects funded by the European Agency for Education, Culture and Audiovisual (EACEA) of the European Commission, Jean Monnet (Erasmus +): Jean Monnet Module EUCOPOL (reference: 587167-EPP-1-2017-1-ES-EPPJMO-MODULE); and Jean Monnet Network OPENEUDEBATE (reference: 600465-EPP-1-2018-1-ES-EPPJMO-NETWORK). This article is also part of another project (FAKENEWS) funded by the Spanish Research Agency, from the Science, Innovation and Universities department (Reference: RTI2018-097709-B-I00).

Jorge Tuñón is European Ph. D., Lecturer at the University of Madrid (Carlos III) and consultant on European Public Affairs and Communication. He is External Expert of the EU Parliament and EU Commission evaluator. At current, he belongs to the OPENEUDEBATE EU network and leads the European Project “EU Communication Policy: challenge or miracle? EUROPEAN COMMISSION – ERAMUS +, (EUCOPOL).

Uxía Carral is a postgraduate student in Applied Research to Mass Media at the University Carlos III of Madrid. At current, she is a PhD candidate focused on European public sphere and Eurosceptic phenomena (Brexit, populism, etc.). Previously, she has worked for the European OPENEUDEBATE and EUCOPOL projects.

An interesting blog and always good to see fresh angles tackled but it should have been run past a native English speaker.

Thank you, Hugh. You are right. I have just remedied some of the problems. ^Ros

It goes to show we should believe little of what we hear and see especially when the EU upper echelon is involved. In transmitting the information.