How has the Leave vote affected the UK economy, ask Swati Dhingra and Thomas Sampson (LSE) in this second of two blogs based on the CEP Election Analysis briefing on Brexit. It summarizes CEP research on how the referendum outcome has affected the UK economy since 2016. The first blog, which reviews work on the potential long-run economic effects of different forms of Brexit, can be found here.

The full economic impacts of Brexit will not be known for many years. But three and a half years after the referendum, we can assess how the Brexit vote has affected the UK economy since June 2016. The vote has already had economic impacts because economic behaviour depends upon both what is happening now and upon what people and businesses expect to happen in the future. The referendum changed expectations about the future of the UK’s economic relations with the EU and the rest of the world. Not only is Brexit likely to make the UK less open to trade, investment and immigration with the EU, but it has also increased uncertainty. Researchers at the CEP and elsewhere have studied the effect of the Brexit vote on the value of the pound, output, prices, trade, wages and investment.

Sterling

The immediate economic impact of the Brexit vote was a depreciation of sterling. On referendum night, sterling saw the biggest one-day loss that has ever occurred in the four major currencies of the world since the collapse of Bretton Woods. Between 23rd and 27th June 2016, sterling declined by 11 per cent against the US dollar and 8 per cent against the euro, and it has remained around 10 per cent below its pre-referendum value.

Image by Images Money, (CC BY 2.0).

Output

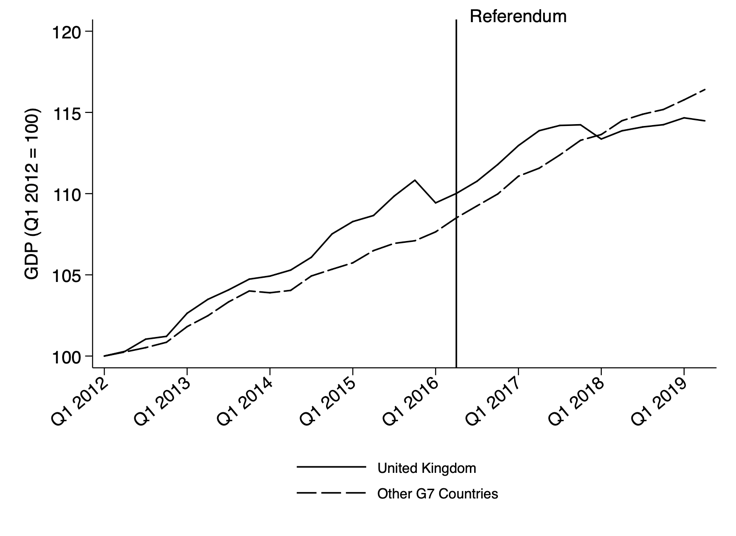

A broad indicator of economic performance is the growth rate of GDP. While the UK started with a steeper growth trajectory, it has fallen behind other G7 countries since the referendum (Figure 1). The Brexit vote is estimated to have reduced UK’s GDP by between 1.7 and 2.5 percentage points lower, or between £1,300 and £2,000 per household in pound terms (Born et al. 2019).

Figure 1: GDP Growth in the UK and Other G7 Countries 2012-19

Source: CEP calculations, updated from De Lyon and Dhingra (2019). GDP values are deflated by country-specific GDP deflators. Other G7 countries include France, Germany, Italy, Japan and the United States.

Prices and the cost of living

Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation rose dramatically from 0.4 percent in June 2016 to 3 percent in January 2018. Breinlich et al. (2019a) study whether this increase in inflation was caused by the Brexit depreciation. If the sterling depreciation is responsible for higher inflation, we would expect product groups where consumers buy more imported goods, such as food and clothing, to have experienced bigger price rises than groups less sensitive to import costs, such as restaurants and hotels. And this is exactly what Breinlich et al. find. After disentangling the effect of higher import costs from other factors that affect prices, Breinlich et al. estimate the Brexit vote increased consumer prices by 2.9 percentage points in the two years following the referendum, which equates to an £870 pound per year increase in the cost of living for the average UK household. It would be wise to view the precise magnitude of this effect with some caution, but the cost is undoubtedly substantial.

Trade

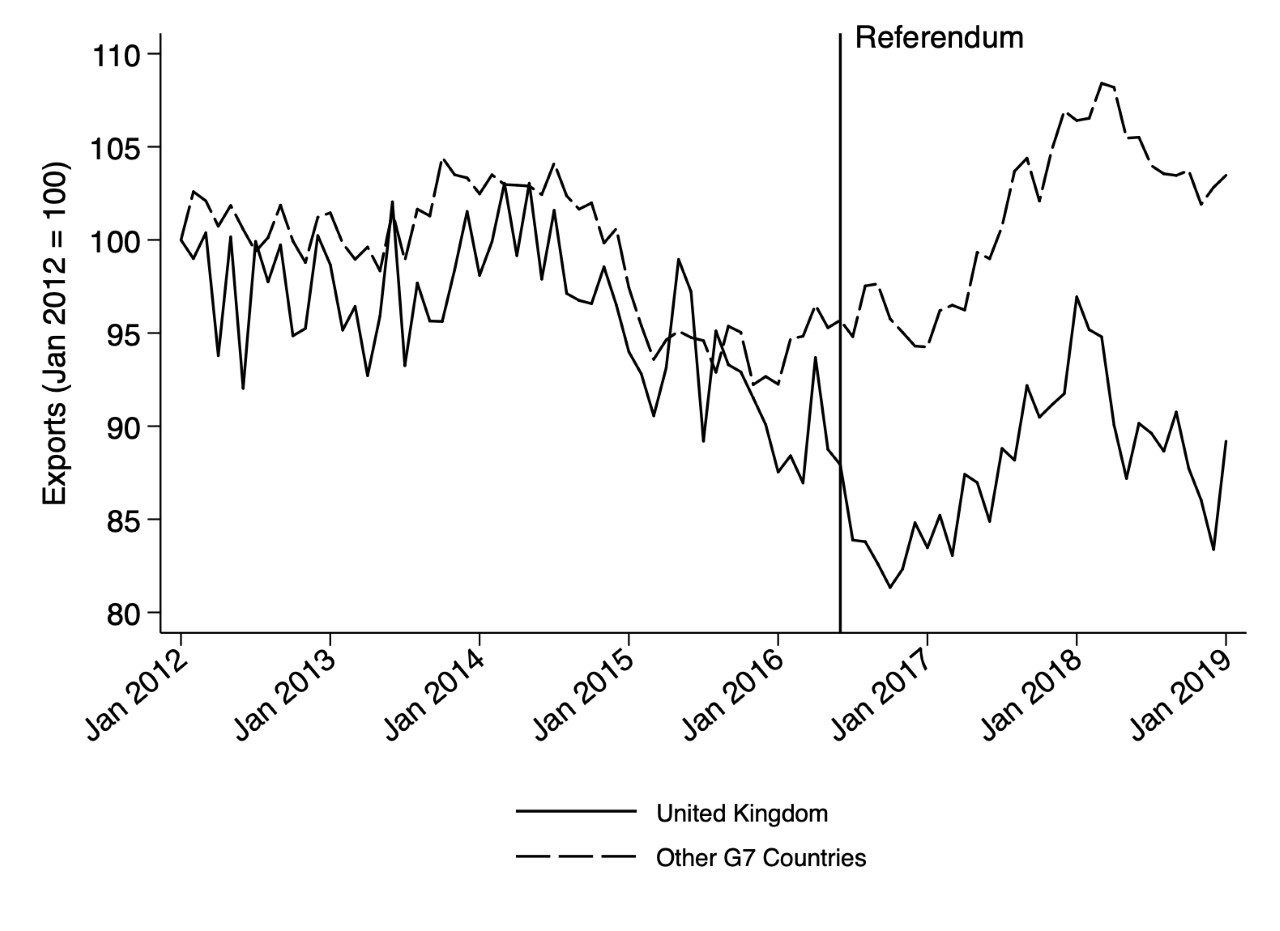

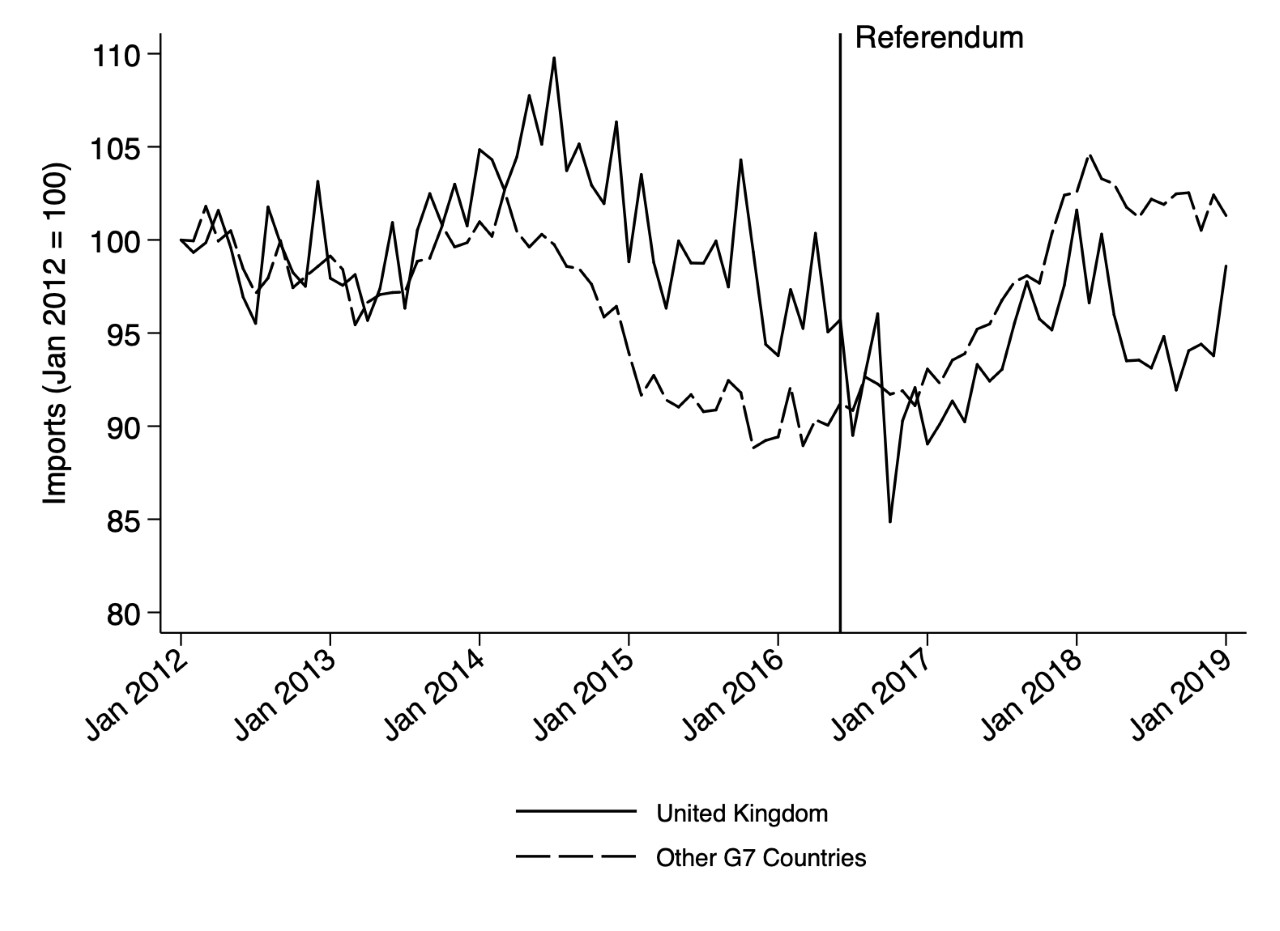

By making UK exports cheaper, the depreciation of sterling following the referendum could, in principle, give UK firms a competitive advantage in foreign markets leading to higher exports. However, real export growth has not increased since the depreciation, compared to other G7 countries, as shown in Figure 2a. For firms with global supply chains, currency depreciations also raise import costs, mitigating the competitive advantage of the depreciation for exporting. The growth in real imports into the UK has been broadly similar to that in other G7 countries, as shown in Figure 2b. The nominal value of imports has risen, but this is largely because of a rise in import prices due to the sterling depreciation. Analysis by Costa et al. (2019) finds that the rising cost of imported inputs has dominated the potential revenue gains from exports brought about by the depreciation.

Figure 2: Real exports and imports in the UK and other G7 countries, 2012-19

(a) Exports

(b) Imports

Source: Updated CEP calculations from De Lyon and Dhingra (2019). Trade values deflated by country-specific producer price indices (PPIs). Other G7 countries include France, Germany, Italy, Japan and the United States.

Wages and employment

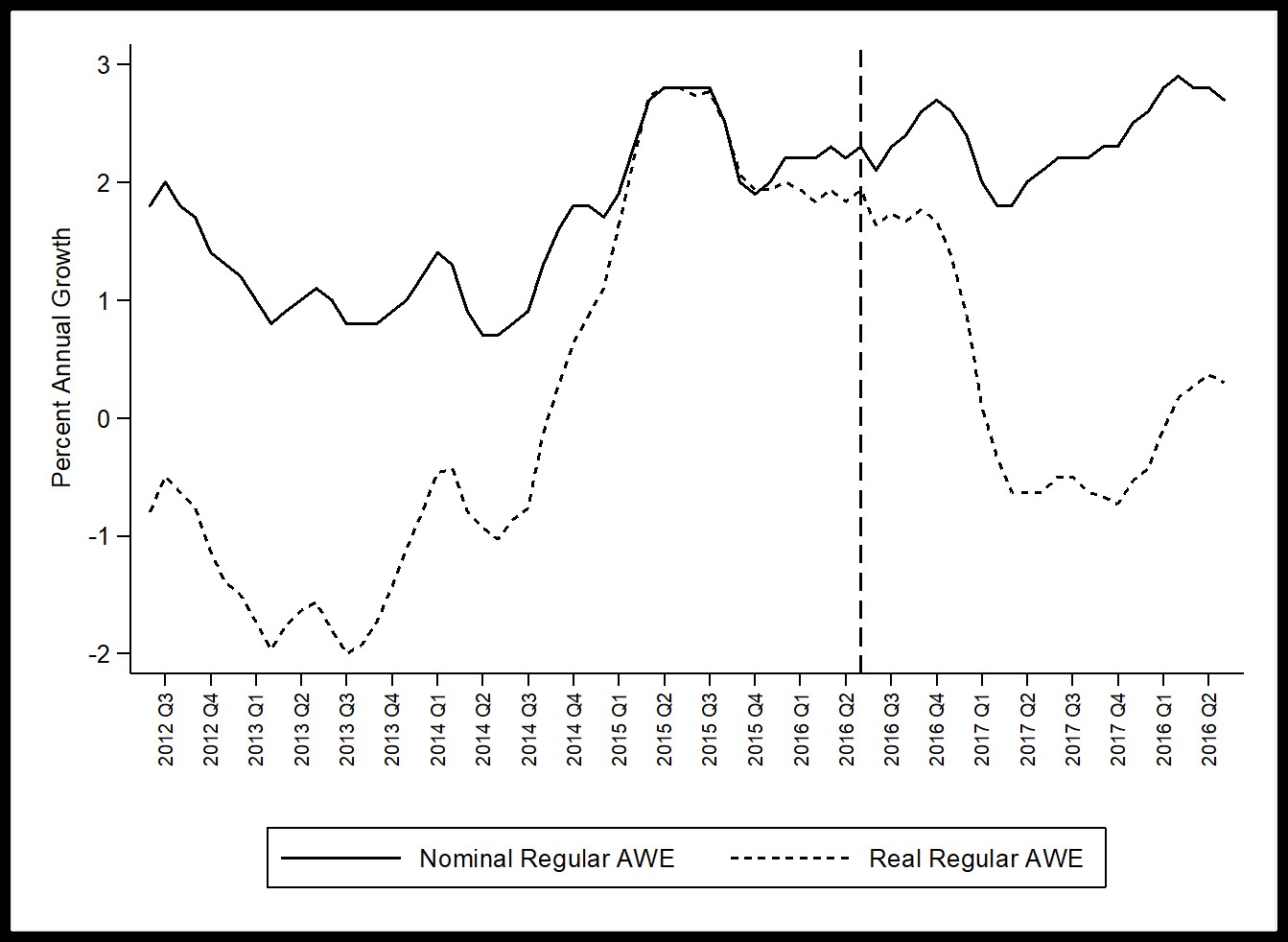

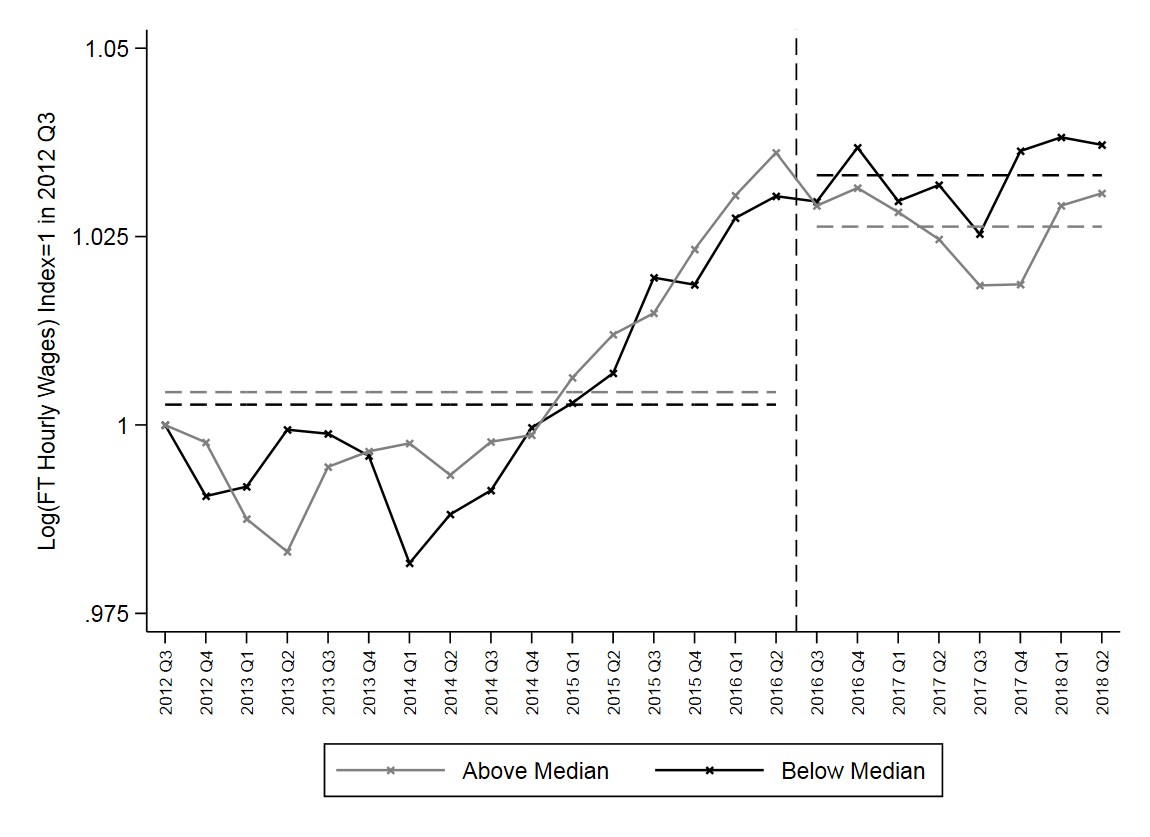

The increase in inflation due to the Brexit depreciation has not been accompanied by faster income growth. As shown in Figure 3a, higher inflation after the referendum led to a decline in real wage growth. Real wages dropped from a pre-referendum annual growth rate of 1.1% to less than 0.1% after the referendum. Research by Costa et al. (2019) sheds more light on the causes of this real wage stagnation. After the referendum, workers in sectors that saw bigger increases in the price of their intermediate imports experienced slower wage growth and reductions in job-related education and training. Comparing sectors in the top and bottom halves of the intermediate import-weighted depreciations, Figure 3b shows real wages in the top half of sectors were growing at 1.3% annually before the referendum and this dropped to -0.6% after the referendum. The slowdown is 1.4 percentage points lower than the exposed sectors in the bottom half, which saw a fall in their annual real wage growth from 1% to 0.4% after the referendum. While wages had been growing in the pre-referendum period, real wages have stagnated since then and this effect is more pronounced in sectors that have been hardest hit by rising costs from the sterling depreciation, as Figure 7 shows.

Rising import costs have not translated into job losses or reductions in hours worked, except paid overtime hours which have seen reductions since the referendum. Overall, the drop in training opportunities and anaemic wage growth at a time of high employment rates raises serious alarm of a deepening of the productivity slowdown that has plagued the UK economy for years.

Figure 3: Wage growth, 2012-18

(a) Nominal and Real Wage Growth In All Sectors

(b) Real Wage Growth in Sectors at the Top and Bottom of Import Cost Exposure

Source: Office for National Statistics and CEP calculations based on Costa et al (2019). Wage growth is the percentage change year on year in the three month average of Average Weekly Earnings – Regular Pay. Real AWE is Nominal AWE deflated by CPI. The dashed vertical line shows the date of the referendum (June 2016).

Investment

Uncertainty makes businesses less willing to invest in risky new projects. Bloom et al. (2019) find that firms that report experiencing higher Brexit-related uncertainty have had lower investment and productivity growth since the referendum. They estimate that anticipation of Brexit reduced business investment in the UK by 11 percent in the three years following the referendum. The Brexit vote has also started to affect investment flows into and out of the UK. Reduced openness makes the UK a less desirable investment destination because it increases the costs of using the UK as a base for serving EU markets. CEP research by Breinlich et al. (2019b) shows that the Leave vote led to a 17% increase in new investment projects by UK firms in the EU by March 2019, but did not affect UK investment outside of the EU. Looking at flows in the opposite direction, Breinlich et al. find that the referendum reduced new investment projects by EU firms in the UK by 9 percent over the same period. Together these estimates suggest that Brexit is making the UK a less attractive place to do business.

Final words

It is too soon to evaluate the accuracy of forecasts that estimate the potential long-run effects of Brexit and as time passes, new evidence will continue to provide fresh information on the response of the economy to Brexit. However, even before Brexit has happened evidence on post-referendum changes in output, prices, trade, wages and investment shows that the UK is paying an economic price for its decision to leave the EU.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE.

1 Comments