In 1997 all the main parties promised a referendum on whether Britain should join the euro, but eventually Labour ruled out membership. Anti-euro campaigners went on to hone their arguments in the 2016 referendum. Stuart Smedley (King’s College London) suggests that this may have been a missed opportunity for the government to tackle Eurosceptic narratives.

Early historical accounts of the United Kingdom’s engagement with the process of European integration categorised the failure to join the European Coal and Steel Community and European Economic Community at their launch as representing ‘missed opportunities’. These decisions, it was argued, denied Britain a leadership role in Europe, which accession to the EEC in 1973 only partially rectified. With time, however, this historical interpretation came to be challenged as more measured assessments of these decisions emerged.

Yet in light of the outcome of the 2016 referendum, it is worthwhile revisiting the ‘missed opportunities’ thesis and using it as a frame through which to analyse domestic aspects of Britain’s European integration policy. One decision in particular stands out as being worthy of such treatment: the failure of Tony Blair’s Labour government to hold a referendum on joining the single European currency.

On the face of it, this may seem like a sensible policy choice. It appeared highly likely that a referendum would have led to the British public rejecting the euro. Indeed, referendum voting intention polling on the subject showed a consistently strong lead for those who would vote ‘No’ – even when the public were presented with a hypothetical scenario in which the government recommended a vote in favour.

However, through an analysis of the Blair government’s policy towards the euro, campaign material produced by anti-euro campaign groups, as well as historical opinion poll data, it becomes apparent this was arguably a ‘missed opportunity’ – and that Labour perhaps should have held a referendum on the principle of British membership of the single currency.

Alongside the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats, ahead of the 1997 general election Labour promised that any decision to join the planned single currency would require the consent of the British public. For Labour, a referendum would be the final stage of the path towards adopting the euro, but it would only have been held if Cabinet and Parliament had provided their approval. Labour also insisted that any decision to join would have to be ‘determined by a hard-headed assessment of Britain’s economic interests’. As a result, in October 1997 Chancellor Gordon Brown set out the five economic tests that would have to be satisfied.

Yet the five tests, along with the National Changeover Plan announced in 1999, seemed to signal that the government was making preparations to adopt the single currency – and thus to hold a referendum. This speculation was fuelled further by the Eurosceptic press. But Labour did not help themselves. Indeed, it was not until June 2003 – five and a half years after they were initially announced – that the five tests were reassessed. During that time, Europe sustained a high level of public salience. According to Ipsos MORI’s Issues Index, prior to the 1997 general election a record 43% of British adults mentioned Europe as an important issue facing Britain (this was the highest level of importance it would achieve until February 2017). While concern declined after Labour entered office, between 1998 and 2000 Europe’s average monthly importance matched that for unemployment – the dominant issue of the early 1990s – and was only bettered by health and education. Furthermore, Europe’s salience only receded after the 2003 assessment of the five tests, an event which made it clear that Britain would not be joining the euro.

Anti-euro campaign groups subsequently took advantage of this situation, launching a form of proxy campaign in which their views went largely unchallenged. The most prominent organisations established were Business for Sterling (whose early Head of Research was a certain Dominic Cummings) and New Europe. These groups would then merge to form the ‘No’ campaign in 2000. With the support of prominent business organisations, including the Institute of Directors (IoD), these groups expressed doubts about the economic case for adopting the single currency. Intriguingly though, they did not outright reject the euro’s purported economic benefits. Instead they merely argued against adoption ‘for the foreseeable future’ on economic grounds.

But the questioning of the economic case appeared to be a means to lend greater credibility to the far more emotive reasons they gave for rejecting the single currency. The crux of their arguments against the euro related to control and identity – two themes that not only resonated with the public, but further embedded themselves in popular discourse about the EU and variations of which were returned to with great effect in the 2016 referendum.

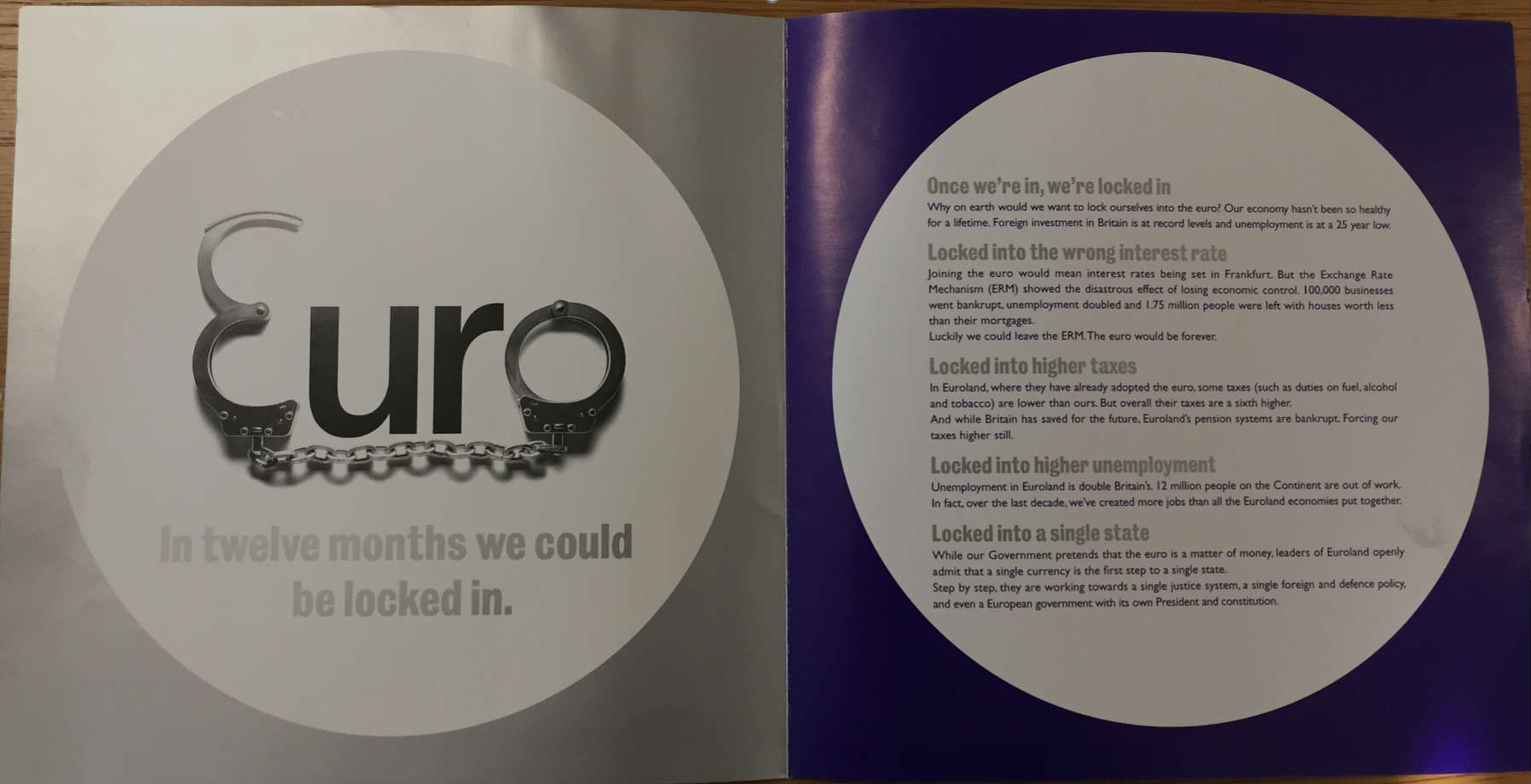

The idea that adopting the euro would see Britain lose control over key aspects of economic policy was one that featured heavily in the campaign groups’ literature, examples of which can be found in the LSE Archive’s ‘Eurosceptic’ collection. The ‘No’ campaign even produced a leaflet that used a pair of handcuffs to depict the effects of the currency, which they claimed would ‘lock’ Britain into economic policies that would be heavily to its disadvantage.

‘No’ campaign leaflet, undated but probably 2000 or 2001 (LSE/EUROSCEPTIC/11/3)

Arguments about control tapped into a belief strongly evident among the British public. Eurobarometer surveys conducted in 1995, 1996, 1998 and 2001 found that between six in ten and two-thirds of British adults felt that joining the single currency would ‘imply that Britain will lose control over its economy policy’. Unsurprisingly, this view was held by an overwhelming majority with a negative view of the EU. But even those who considered Britain’s EU membership to be a good thing were more likely to accept this argument, with around half doing so in 1995 and 1996.

Public opinion in Britain on whether the euro will or will not… (Source: Eurobarometer)

| 1995 | 1996 | 1998 | 2001 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Imply that Britain will lose control over its economic policy | ||||

| Will % | 66 | 64 | 62 | 59 |

| Will not % | 21 | 22 | 20 | 17 |

| Don't know % | 13 | 14 | 18 | 24 |

| Imply that Britain will lose too much of its national identity | ||||

| Will % | 66 | 63 | 62 | |

| Will not % | 26 | 28 | 22 | |

| Don't know % | 9 | 10 | 13 | |

Note: Data are based on the author’s own calculations and have been taken from the following Eurobarometer files in each year: EB44 and EB44.1 (1995), EB45.1, EB46 and EB46.1 (1996), EB50 (1998) and EB55 (2001). Data have been filtered to adults aged 18 and over in Great Britain in order to reflect those of voting age. Percentages may not total 100 due to rounding.

In 2001, the question used was altered to ask the extent to which respondents agreed or disagreed that the euro will lead to various outcomes. For the purpose of this post, in the table above those answering ‘Totally agree’ and ‘Somewhat agree’ have been combined as have those answering ‘Totally disagree’ and ‘Somewhat disagree’. Strictly speaking though, 2001 data is not directly comparable to that shown for previous years.

Anti-euro groups also sought to portray the euro as another step towards undermining the sovereignty and identity of nation states. In a 1998 booklet, Business for Sterling labelled the currency as ‘a political project [that] flows from an ambition to create a single political and economic entity in Europe’. Meanwhile, in a pamphlet authored by the economist Sir James Ball, New Europe described the euro as ‘a key element in the march towards some form of European Federal State’ and that it was ‘a gross deception for the British government to pretend otherwise’.

The most similar notion tested on Eurobarometer related to the idea that adopting the euro would ‘imply that Britain will lose too much of its identity’. A clear majority felt this would occur, with around two-thirds doing so. Among those with negative opinions of Britain’s EU membership, the size of the majority agreeing with this statement was again substantial. In contrast, although around half who believed EU membership to be a good thing disputed the idea in 1996 and 1998, comfortably more than a third accepted this argument regarding the euro and national identity.

It is therefore clear that anti-euro groups grasped the mood of public opinion in Britain regarding the single currency. Yet with no referendum called, their arguments went largely unchallenged. To confound matters, Labour’s prevarication over holding a vote and the policy measures taken regarding the single currency fuelled speculation and uncertainty, which these campaign groups made the most of.

Having developed arguments that struck an obvious chord – and with veterans of the anti-euro campaign engaged in the Leave campaign – the anti-euro groups’ narratives would be reimagined to great effect in the 2016 vote on Britain’s EU membership. And for this reason, Labour’s decision not to hold a referendum on the single currency can even be seen as a missed opportunity with significant long-term consequences.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor LSE.

The issue of a referendum on the Euro is, I would argue, simply a sub issue of a greater problem. This is the reluctance of UK governments of all colours (Tory, Labour, Coalition) to admit how much the UK has become increasingly connected with the EU since joining the then EEC in 1973.

There was one referendum in 1975, and then nothing more until 2016. In the meantime, the vast quantity of EU regulations and directives that had an effect on UK law were passed off as initiatives of the UK government, with no explanation of the role of the EU.

One can compare for example the situation in the Irish Republic, which joined the EEC at the same time as the UK in 1973. There referendums were held on the Single European Act (1987), Maastricht Treaty (1993), Amsterdam Treaty (1999), and Lisbon Treaty (2009). This kept the Irish electorate on board as the EU increasingly apparently encroached on Irish sovereignty. Eurobarometer surveys show current Irish support for the EU around an amazing 90%!

Yes there was a missed opportunity. It was the arrogant way in which Labour handled the 2007-08 Lisbon Treaty in Britain which helped to set the conditions for what followed less than a decade later. We were promised a referendum on the European Constitution but then denied it under the pretence that the Lisbon treaty was something different. Had we decided to leave then, it would have been a lot less painful than now.