Nostalgia is one of the reasons often cited for the Leave vote. But what kind? Lindsay Richards (University of Oxford) identifies two underlying dimensions of nostalgia – ‘traditional’ and ‘egalitarian’. People with high levels of egalitarian nostalgia were just as likely to vote Remain as those who weren’t nostalgic at all.

Two parallel narratives have accompanied debates around the stubborn British preference for leaving the EU. The first is the claim that Brexit voters had been ‘Left Behind’ by social change. The left behind (we are told) are the ones who lost out during the globalisation years, staying at the bottom of the income distribution while the rest were pulling away. They are not just economically marginalised, but lost in the modern way of thinking too; attitudes to immigration, ethnic diversity, and gender roles have not moved on so much for the left behind. The second narrative relates to nostalgia for ‘a golden age’ which featured large in the political discourse. “Take Back Control” was a clever slogan in many ways. Particularly, perhaps, the word “back”: it implies something we used to have, something lost. Another obvious example was the success of Trump’s “Make America Great Again” (because it was once great at some point in the past but now it’s gone). This discourse seems to strike a chord with many individuals.

Several commentators have invited us to empathise with those feeling left behind by social change. David Goodhart, in his 2017 book on a Britain divided by preferences and values, writes about “cultural anxiety” and “people who feel adrift”. A 2018 report by Demos described the feelings of displacement as “shared cultures, traditions and values – are being displaced by an emphasis on pluralism”. Justin Gest’s 2016 book describes the “poignant nostalgia” of the white working class who feel dislodged in the social hierarchy by immigrants and ethnic minorities.

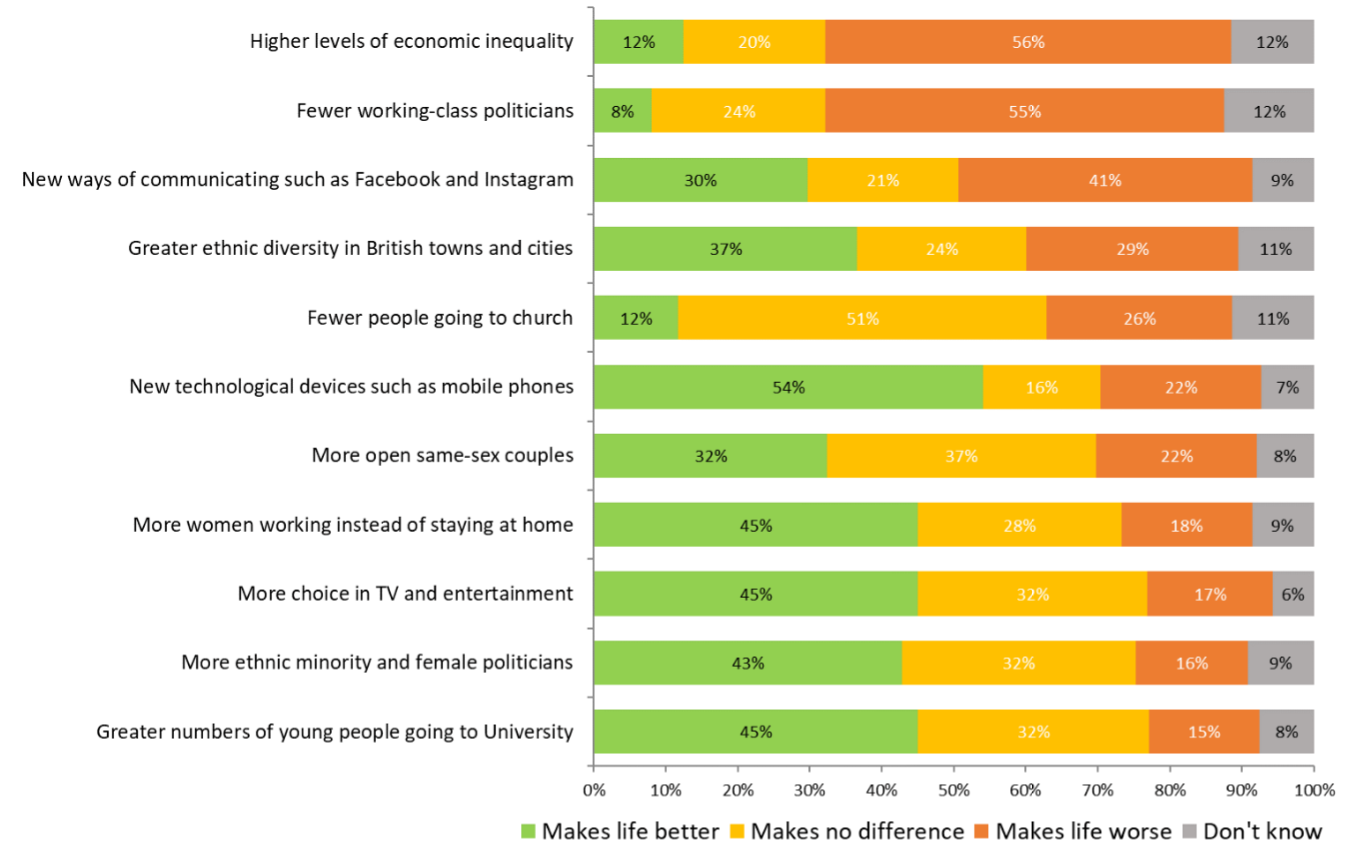

But what can we learn when we look past the loaded discourse? In a recent study, we wanted to understand preferences for the past and their implications for political preferences, so we put together a set of questions and asked them to a representative sample of 3000 people in the UK. For eleven different aspects of social change, we asked “Do you think these aspects of modern life make life worse, or make life better?” We selected social changes giving broad coverage (i.e. are not just about immigration and ethnicity) and also that are common knowledge and uncontroversial.

Figure 1

Figure 1 shows that the majority of British people report that higher levels of economic inequality and the lack of working class politicians make life worse. New ways of communicating (Facebook and Instagram) are also unpopular. The items that had the lowest numbers saying ‘make life worse’ include greater opportunities to go to university, the increase in ethnic minority and female politicians, and more choice in TV and entertainment. On some items, the proportion saying ‘makes no difference’ is rather high, particularly for the level of church attendance and more open same sex couples. This middle answer option perhaps ought not to be treated as indifference towards the social change but rather as modest acceptance (e.g. ‘I don’t mind that fewer people go to church these days’).

We were interested to know if there was more than one underlying type of nostalgia and we examined how answers to the eleven questions tended to cluster together. Our results suggested two underlying dimensions of nostalgia. The first we label ‘traditional nostalgia’, which is characterised by high levels of people saying “making life worse” for ethnic diversity, diversity among politicians, women working, and open same-sex couples. The second dimension we label ‘egalitarian nostalgia’, which is characterised by high levels of saying “making life worse” on economic inequality and the professionalisation of the political class. It is possible by our measure for individuals to have both types of nostalgia at once, or neither, as well as one or the other.

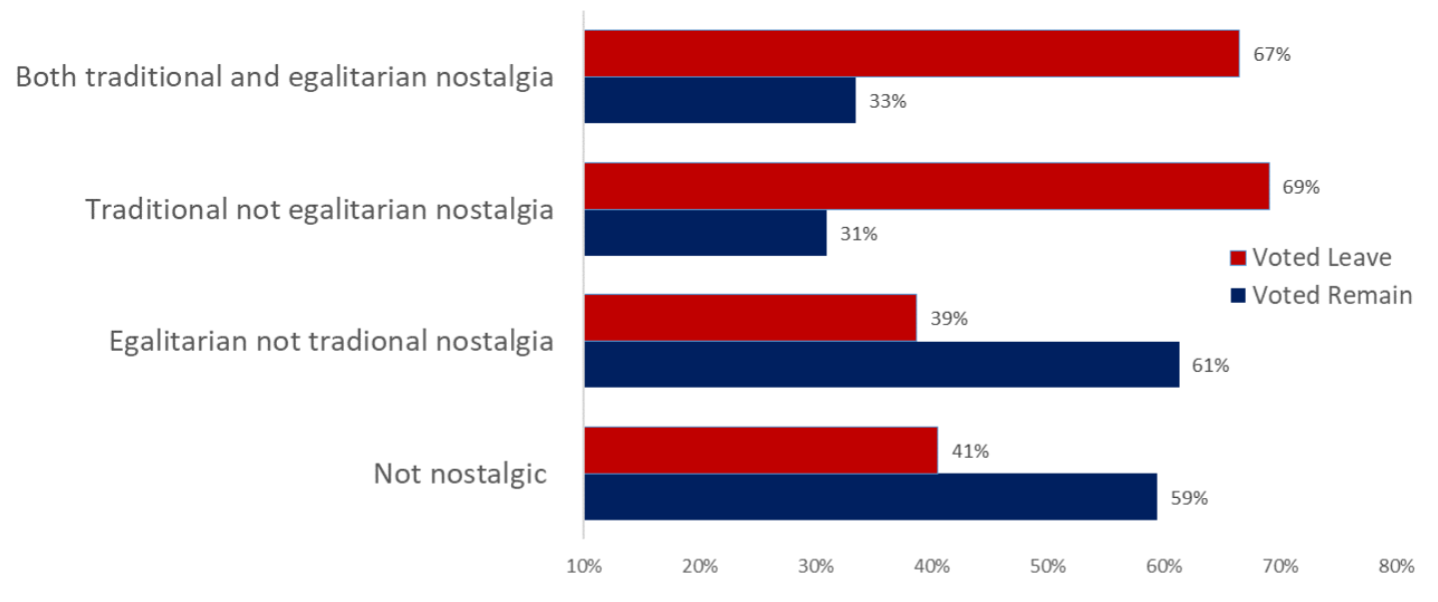

How do these nostalgia types relate to preferences for Brexit? It is perhaps not surprising, since it fits the left behind–nostalgia narrative, that people who report higher levels of traditional nostalgia are much more likely to have voted Leave in the referendum. This is the case whether they have nostalgia only of the traditional type, or if in combination with egalitarian nostalgia – see Figure 2. We also see, as expected, that people who don’t feel nostalgic for the past on either dimension were much more likely to have voted for Remain. However, the interesting point, given the assumption that the Leavers are the nostalgic ones, is that people who have high levels of egalitarian nostalgia were just as likely to vote Remain as those who weren’t nostalgic at all.

Figure 2

It seems evident that those with high levels of traditional nostalgia are not fully at home in modern Britain. The world they wish for is ethnically homogeneous, with traditional family structures and gender roles, a world long gone and irretrievable. Perhaps British society never existed in its idealised nostalgic form. Egalitarian nostalgia is possibly of a more optimistic utopian type, being pro-social in its concern with political representation and better economic outcomes for the many. These results confirm the idea of a cultural divide in Britain, but it is not a divide as simple as the nostalgic versus the not. The patterns of clustering that define our nostalgia types are perhaps familiar patterns of attitudinal clusters; we do not wish to claim that the clusters are new but rather that we must look at the content of the nostalgia in order to understand its link to political preferences. It highlights the need to see nostalgia for what it really is – a social construction reflecting the sentiments that flourish in political discourse – not as a satisfactory justification or explanation of political preferences per se.

The danger is, in the same way that ‘left behind’ is used to legitimise or rationalise the Brexit vote, that nostalgic explanations can see ethnic, gender, and other inequalities discarded from the conversation. To use Gurminder Bhambra’s terms, we must make sure that nostalgia is not ‘a euphemism for a racialised identity politics’. Nor indeed should we forget that many Remainers feel adrift in the modern world too, missing their own vision of a golden past.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor LSE.